China social media: WeChat and the Surveillance State

- Published

China's WeChat is a site for social interaction, a form of currency, a dating app, a tool for sporting teams and deliverer of news: Twitter, Facebook, Googlemaps, Tinder and Apple Pay all rolled into one. But it is also an ever more powerful weapon of social control for the Chinese government.

I've just been locked out of WeChat (or Weixin 微信 as it is known in Chinese) and, to get back on, have had to pass through some pretty Orwellian steps - steps which have led others to question why I went along with it.

One reason is that life in Beijing would be extremely difficult without WeChat. The other is that I could not have written this piece without experiencing the stages which have now clearly put my image, and even my voice, on some sort of biometric database of troublemakers.

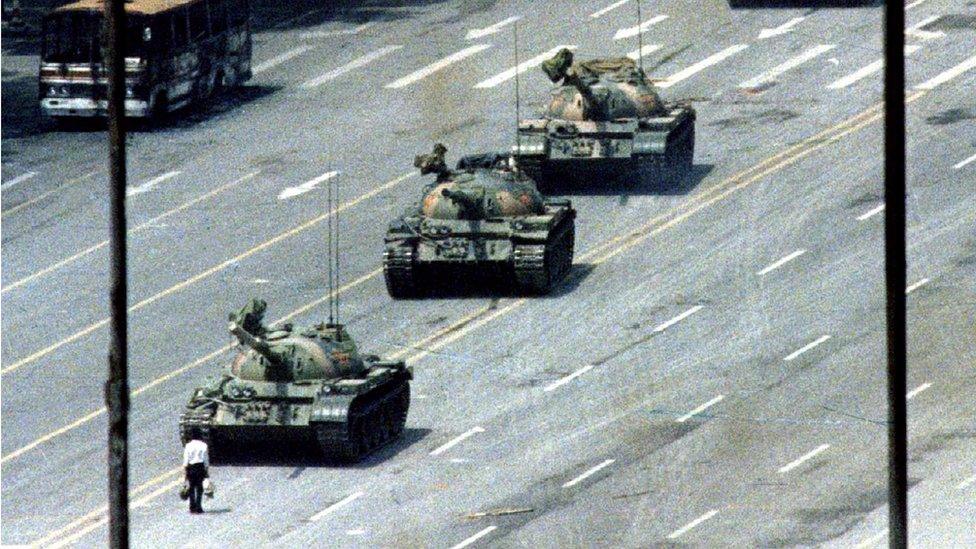

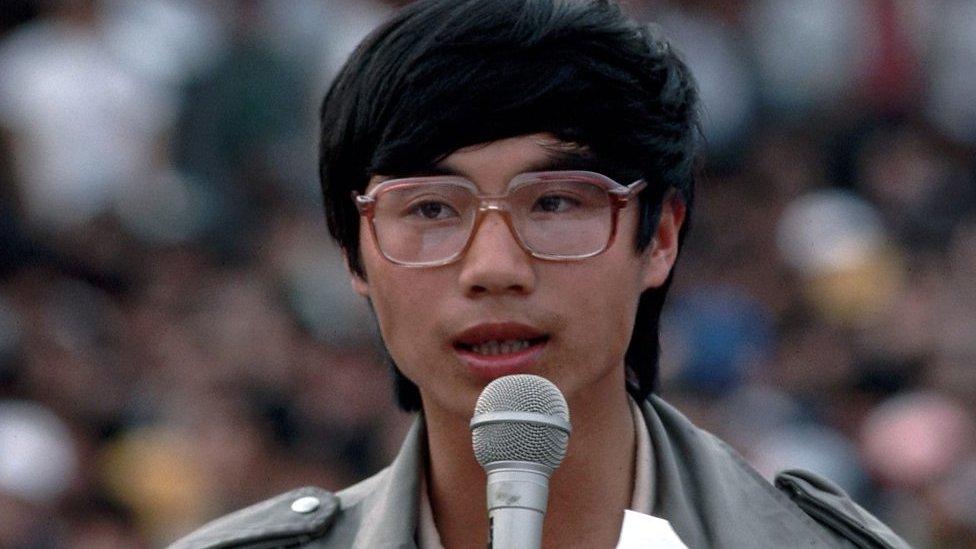

I was in Hong Kong to cover the enormous candlelight vigil marking 30 years since the People's Liberation Army was ordered to open fire on its own people to remove the mostly student protesters who'd been gathering in and around Tiananmen Square for months in June 1989.

This moment in history has been all but erased from public discourse on mainland China but in Hong Kong, with its special status in the Chinese-speaking world, people turn out every year to remember the bloody crackdown.

This time round the crowd was particularly huge, with estimates ranging up to 180,000.

Naturally I took photos of the sea of people holding candles and singing, and posted some of these on my WeChat "moments".

Tiananmen's tank man: The image that China forgot

The post contained no words - just photos.

Chinese friends started asking on WeChat what the event was? Why were people gathering? Where was it?

That such questions were coming from young professionals here shows the extent to which knowledge of Tiananmen 1989 has been made to disappear in China.

I answered a few of them, rather cryptically, then suddenly I was locked out of WeChat.

"Your login has been declined due to account exceptions. Try to log in again and proceed as instructed," came the message on the screen.

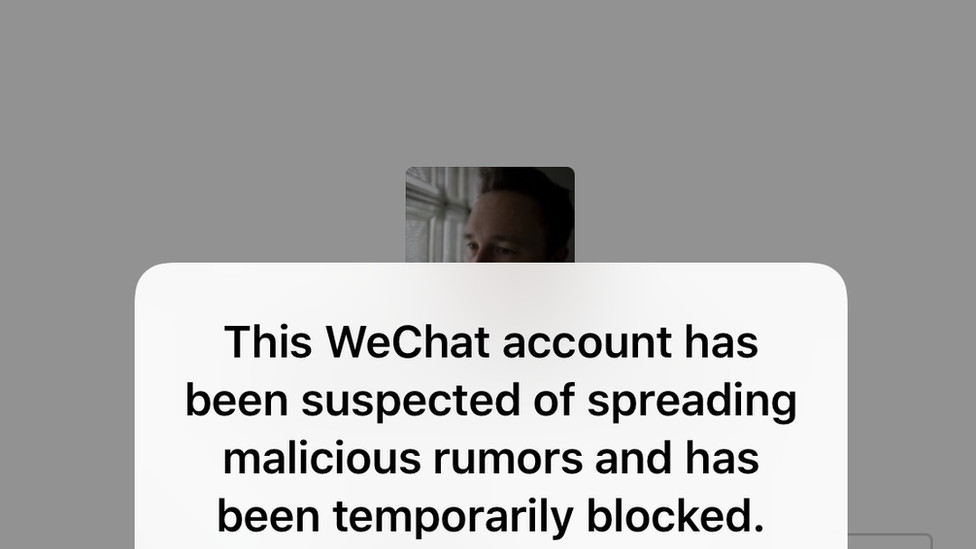

Then, when I tried to log back in, a new message appeared: "This WeChat account has been suspected of spreading malicious rumours and has been temporarily blocked…"

It seems posting photos of an actual event taking place, without commentary, amounts to "spreading malicious rumours" in China.

I was given time to try and log in again the next day after my penalty had been served.

When I did I had to push "agree and unblock" under the stated reason of "spread malicious rumours".

So this rumour-monger clicked on "agree".

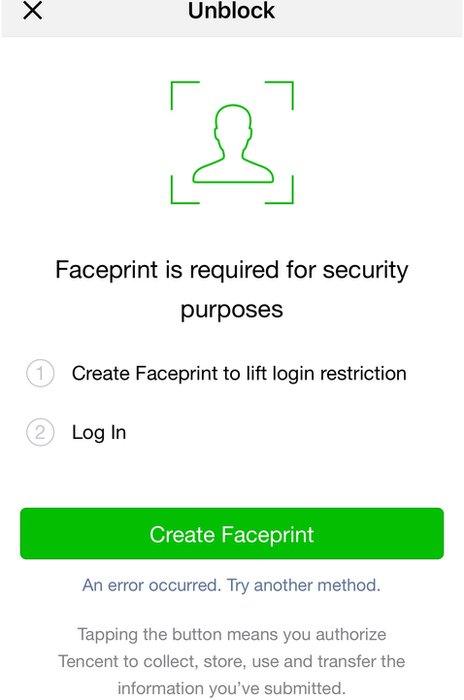

Then came a stage I was not prepared for. "Faceprint is required for security purposes," it said.

I was instructed to hold my phone up - to "face front camera straight on" - looking directly at the image of a human head. Then told to "Read numbers aloud in Mandarin Chinese".

My voice was captured by the App at the same time it scanned my face.

Afterwards a big green tick: "Approved"

Apart from being creepy you can only imagine the potential use of this type of data.

No doubt I have now joined some list of suspicious individuals in the hands of goodness knows which Chinese government agencies.

In China pretty much everyone has WeChat. I don't know a single person without it. Developed by tech giant Tencent it is an incredible app. It's convenient. It works. It's fun. It was ahead of the game on the global stage and it has found its way into all corners of people's existence.

It could deliver to the Communist Party a life map of pretty much everybody in this country, citizens and foreigners alike.

Capturing the face and voice image of everyone who was suspended for mentioning the Tiananmen crackdown anniversary in recent days would be considered very useful for those who want to monitor anyone who might potentially cause problems.

When I placed details of this entire process on Twitter others were asking: why cave in to such a Big Brother intrusion on your privacy?

They've probably not lived in China.

It is hard to imagine a life here without it.

When you meet somebody in a work context they don't given you a name card any more, they share their WeChat; if you play for a football team training details are on WeChat; children's school arrangements, WeChat; Tinder-style dates, WeChat; movie tickets, WeChat; news stream, WeChat; restaurant locations, WeChat; paying for absolutely everything from a bowl of noodles to clothes to a dining room table… WeChat.

People wouldn't be able to speak to their friends or family without it.

So the censors who can lock you out of Wechat hold real power over you.

The app - thought by Western intelligence agencies to be the least secure of its type in the world - has essentially got you over a barrel.

If you want to have a normal life in China, you had better not say anything controversial about the Communist Party and especially not about its leader, Xi Jinping.

This is China 2019.

- Published30 May 2019

- Published22 May 2019

- Published19 April 2019