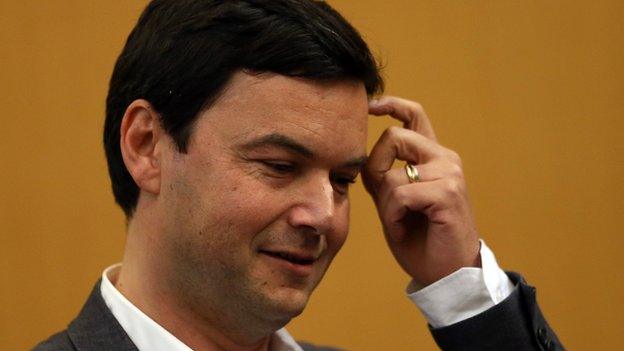

Thomas Piketty: The French economist US liberals love

- Published

- comments

Thomas Piketty has been compared to a modern-day Alexis de Tocqueville

If you want to mingle with the educated elite this weekend, you need to know a little bit about French economist Thomas Piketty and his surprise best-selling book, external, Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Mr Piketty uses tax data from a variety of Western countries to tackle the question of income inequality in today's society. He focuses in particular on the increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of an elite few - the much-talked-about "one percent".

Here's how New York Times columnist Paul Krugman describes, external Mr Piketty's "big idea" in the New York Review of Books:

We haven't just gone back to nineteenth-century levels of income inequality, we're also on a path back to "patrimonial capitalism," in which the commanding heights of the economy are controlled not by talented individuals but by family dynasties.

This is happening, Mr Piketty writes, because the rate of return on capital has been outpacing the rate of economic growth. In layman's terms, the rich are getting richer.

To halt this "drift toward oligarchy", Mr Piketty calls for new a progressive tax on capital - preferably a global one, to prevent wealth from being moved to low-tax nations.

Commentators and columnists on the left have embraced Mr Piketty's book as a landmark treatise that encapsulates what they see as the challenge facing modern US society.

Prof Jacob S Hacker of Yale and Prof Paul Pierson of the University of California - Berkeley call, external Mr Piketty a modern-day Alexis de Tocqueville, presenting a new "panoramic vista" of US democracy and society.

"Like Tocqueville, Mr Piketty has given us a new image of ourselves," they write. "This time, it's one we should resist, not welcome."

Slate's Jordan Weissmann says, external that Mr Piketty has handed liberals a "coherent framework that justifies the discomfort that they probably already felt about the wealth gap".

"Liberals, instead of nebulously arguing that they're fighting for the middle class, now have a touchstone that clearly argues they're fighting against the otherwise inevitable rise of the Hiltons," he writes.

"Whether or not Mr Piketty's grand unified theory is exactly correct," he concludes, "he's moving the popular conversation in the right direction."

To give an appreciation for just how much of a conversation topic Mr Piketty's book has become, it was the subject of two columns in Friday's New York Times - one, external by liberal Krugman and the other, external by conservative columnist David Brooks.

Krugman writes that Capital "demolishes that most cherished of conservative myths, the insistence that we're living in a meritocracy in which great wealth is earned and deserved".

Brooks counters that the buzz over Mr Piketty's book is due to the fact that professional liberals often rub elbows with, and are increasingly jealous of, the super-wealthy.

"The reaction to Mr Piketty is an amazing cultural phenomenon," he writes. "But it says more about class rivalry within the educated classes than it does about how to really expand opportunity."

Capital's point, Brooks writes, is that "inequality is not driven by young hip professionals who arm their kids with every advantage and get them into competitive colleges; it's driven by hedge fund oligarchs."

"Well, of course, this book is going to set off a fervour that some have likened to Beatlemania," he concludes.

The National Review's James Pethokoukis worries, external about the consequences if Mr Piketty's "economic agenda" is successfully "pushed by Washington Democrats and promoted by the mainstream media".

"The soft Marxism in Capital, if unchallenged, will spread among the clerisy and reshape the political economic landscape on which all future policy battles will be waged," he writes.

"Who will make the intellectual case for economic freedom today?" he asks.

In the Wall Street Journal Daniel Shuchman calls, external Mr Piketty's book "less a work of economic analysis than a bizarre ideological screed".

He says that Mr Piketty appears to be more preoccupied with inequality than with actual economic growth.

"He assumes that the economy is static and zero-sum; if the income of one population group increases, another one must necessarily have been impoverished," Shuchman writes. "He views equality of outcome as the ultimate end and solely for its own sake."

Mr Piketty's 685-page opus has started a legitimate debate in US political circles. More surprisingly its best-selling success indicates that this conversation is spilling into backyard barbeque and pub table discussions, as well.