Bundy, Sterling and racism in America

- Published

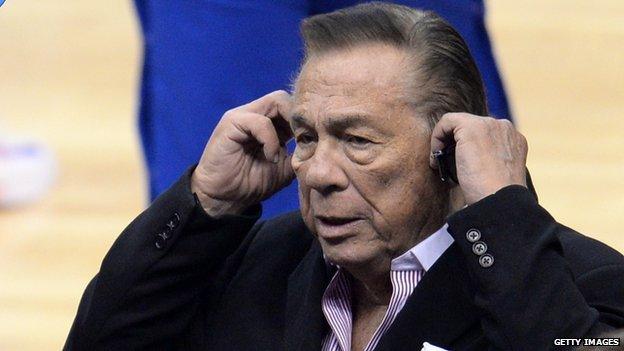

Basketball franchise owner Donald Sterling's alleged comments have made him the latest face of racism in the US

What do the stories of Cliven Bundy and Donald Sterling tell us about the state of race relations in the US today?

With two high-profile instances of recorded racist comments making headlines in the space of a week, the kind of people who get paid to speculate on such matters are searching for an answer.

First Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy, who was protesting against government attempts to round up cattle he was illegally grazing on federal land, wondered whether blacks were "better off" under slavery.

Then Donald Sterling, the owner of the professional basketball team the Los Angeles Clippers, was allegedly recorded instructing his girlfriend not to share pictures of herself with blacks on social media or bring them to his team's games.

Salon's Joan Walsh writes, external that Mr Bundy and Mr Sterling share "an ignorant, self-serving paternalism".

She notes that Mr Sterling said he gives his black players "food, and clothes, and cars, and houses". This is only "a few bad leaps of logic" away from Mr Bundy's theorising that slavery provided blacks "homes with their chickens and their gardens and their children around them, and their man having something to do".

Politics entered the discussion very early on. As writers on the left noted, Mr Bundy had been embraced by many conservatives as a right-wing folk hero, standing up against an overreaching federal government.

Conservatives initially thought they had found an ideological counterpoint in the Sterling story, as he had made political donations to Democrats, external in the past. It turns out, however, that Mr Sterling is a registered Republican, external.

But beyond the shallow debate over political affiliation is the question of whether the views of the two men are still representative of any significant segment of the US public.

Both Mr Bundy and Mr Sterling are "old men who live in a form of isolation", writes, external HotAir.com's Jazz Shaw.

"Bundy lives in a geographically isolated, rural region," he says. "Sterling lives in the rather insular world of the very wealthy. They also come from a different generation, growing up among attitudes which were common beyond notice in their day but which would probably shock many people today."

Shaw writes that he is optimistic, however, that younger generations are leaving this kind of bigotry behind.

"We seem to be raising a generation of young adults who simply don't fall into these old pigeonholes and are more interested in the joint challenges they all face in today's society," he concludes.

CNN's LZ Granderson isn't so sure. He writes, external that while Mr Bundy and Mr Sterling may be racists, they are just "lightning rods of the moment". Today's racism has a different face.

"Racism 2.0 is busily working in the shadows, gerrymandering away voting rights and creating legislation that makes pre-emptively shooting dead a young black man who makes you nervous synonymous with standing one's ground," he says.

Does this mean racism is getting worse in the US? Mediaite's Joe Concha says, external that it's hard to know for sure:

On one hand, Cliven Bundy's and Donald Sterling's deplorable comments have been universally condemned from left and right, blacks and whites alike. On the other hand, it feels like the divide is getting deeper - especially since the media-fueled polarization of the George Zimmerman trial and verdict.

He wonders whether it may just be a reflection of our modern media culture, where "too many people on the extremes have been given a microphone".

Cliven Bundy made headlines with comments about blacks and slavery

Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson writes, external that despite the insistence by "Republicans, Fox News and a majority of the US Supreme Court" that government programs and legislation to combat racism are no longer necessary, "naked prejudice" hasn't gone away:

Some big-city school systems are as segregated as they were in the 1960s. Leading public universities are admitting fewer black students than a decade ago. The black-white wealth gap has grown in recent years. Blacks are no more likely than whites to use illegal drugs, yet four times more likely to be arrested and jailed for it.

Three weeks ago - before Mr Bundy, before Mr Sterling - Jonathan Chait wrote, external a long piece in New York magazine about how the issue of race in the US has "saturated" the Obama presidency. Despite early hopes that Barack Obama would be a "post-racial" president, race has played a major role in the extreme polarisation of modern US politics and culture.

It has been a hidden - and at times not-so-hidden - subtext to much of our political debate over issues like debt, health care and unemployment.

He ends up siding with those who take hope in future generations overcoming the prejudice of the past:

In the long run, generational changes grind inexorably away. The rising cohort of Americans holds far more liberal views than their parents and grandparents on race, and everything else (though of course what you think about "race" and what you think about "everything else" are now interchangeable). We are living through the angry pangs of a new nation not yet fully born.

A comforting thought, perhaps. For now, however, those "angry pangs" are proving difficult to ignore.

- Published27 April 2014

- Published24 April 2014