Ta-Nehisi Coates and his 'case for reparations'

- Published

- comments

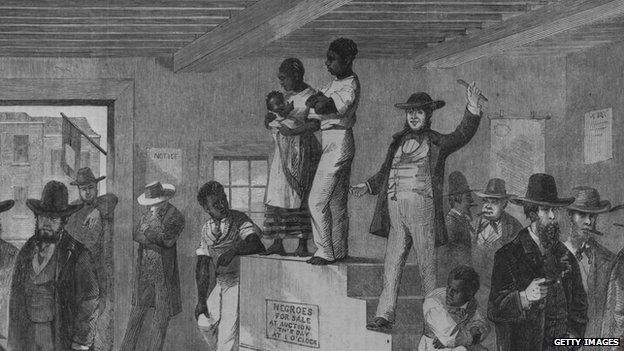

The US was founded, grew and prospered on the back of the black race, writes Ta-Nehisi Coates. And the US will not fully be healed from the legacy of slavery until it confronts this truth and makes amends.

In a much-talked-about 15,000-word cover story for the Atlantic magazine, Coates lays out the case for government reparations to black Americans - for the harms of slavery and for the exploitation of blacks that has continued to the modern day.

In short, slavery, he writes, external, allowed the US to become a powerful, prosperous nation.

"The vending of the black body and the sundering of the black family became an economy unto themselves, estimated to have brought in tens of millions of dollars to antebellum America," he writes.

Slavery created an "indispensable working class", he says, that left "white Americans free to trumpet their love of freedom and democratic values".

After emancipation following the US Civil War, the harm continued on in Jim Crow laws in the South that denied blacks their vote, their property and even their lives.

When blacks moved to Northern cities as part of the Great Migration in the first half of the 20th Century, they faced a different kind of exploitation, he writes - discriminatory housing lenders and government policies designed to keep blacks confined to certain neighbourhoods with fewer services, substandard schools and less opportunity.

"Businesses discriminated against them, awarding them the worst jobs and the worst wages," he writes. "Police brutalised them in the streets. And the notion that black lives, black bodies, and black wealth were rightful targets remained deeply rooted in the broader society."

Even on a national level, policies discriminated against blacks. The Federal Housing Authority refused to offer preferred loans to unstable - ie black - neighbourhoods. Even President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal legislation, including Social Security, was crafted to minimise benefits to blacks, he writes.

Although the overt discrimination has slowly been wiped away, by legislation or judicial action, the US is "still haunted," he says.

"It is as though we have run up a credit-card bill and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear," he writes. "The effects of that balance, interest accruing daily, are all around us."

To Americans who fail to own up to the history of white superiority, taking credit for their nation's achievements but ignoring its failings, Coates says:

The last slaveholder has been dead for a very long time. The last soldier to endure Valley Forge has been dead much longer. To proudly claim the veteran and disown the slaveholder is patriotism a la carte.

Dismissing the legacy of slavery as something in the past or a stain upon American ancestors and not relevant to those alive today is a cop-out, he says: "A nation outlives its generations."

The problem is that the consequences of slavery and the discrimination that continued after the end of civil war has created an intractable wealth gap between whites and blacks.

"The lives of black Americans are better than they were half a century ago," he writes. "The humiliation of Whites Only signs are gone. Rates of black poverty have decreased. Black teen-pregnancy rates are at record lows - and the gap between black and white teen-pregnancy rates has shrunk significantly. But such progress rests on a shaky foundation, and fault lines are everywhere."

Blacks in America are "working without a safety net", he argues. "Financial calamity strikes - a medical emergency, divorce, job loss - the fall is precipitous."

Coates lists some of the ways the US has attempted to address the problem and concludes they are not enough.

Black culture, he says, is not to blame. The idea that if blacks could behave more "respectably" is a sham.

"The kind of trenchant racism to which black people have persistently been subjected can never be defeated by making its victims more respectable," Coates writes. "The essence of American racism is disrespect. "

And placing the blame on broken homes and the absence of black fathers? The destruction of the black family has been a prime means of white control for hundreds of years.

"From the White House on down, the myth holds that fatherhood is the great antidote to all that ails black people," he writes. "Adhering to middle-class norms has never shielded black people from plunder."

Liberal proponents of programmes of racial preferences like affirmative action are equally misguided.

"America was built on the preferential treatment of white people - 395 years of it," he writes. "Vaguely endorsing a cuddly, feel-good diversity does very little to redress this."

Couching preferences as a means of addressing overarching issues of class differences and wealth inequality is fruitless:

To ignore the fact that one of the oldest republics in the world was erected on a foundation of white supremacy, to pretend that the problems of a dual society are the same as the problems of unregulated capitalism, is to cover the sin of national plunder with the sin of national lying. The lie ignores the fact that reducing American poverty and ending white supremacy are not the same. The lie ignores the fact that closing the "achievement gap" will do nothing to close the "injury gap," in which black college graduates still suffer higher unemployment rates than white college graduates, and black job applicants without criminal records enjoy roughly the same chance of getting hired as white applicants with criminal records.

And so, he concludes, monetary reparations - closing the wealth gap between white and black - is the only workable solution. It is also the only way to truly put the legacy of slavery behind us as a nation.

"What is needed is an airing of family secrets, a settling with old ghosts," he writes. "What is needed is a healing of the American psyche and the banishment of white guilt."

He cites as an example the German reparations to Israel following the Holocaust, undertaken despite fierce opposition in both nations:

Reparations could not make up for the murder perpetrated by the Nazis. But they did launch Germany's reckoning with itself, and perhaps provided a road map for how a great civilisation might make itself worthy of the name.

After laying out his case over thousands of words, and spanning hundreds of years, Coates's call to action is, in fact, relatively modest. He wants the US Congress to pass a bill proposed by Democratic Representative John Conyers of Michigan to study slavery and recommend "appropriate remedies".

Maybe the study won't be able to come up with a number, he writes. Perhaps the number will be so monumentally large that it is unworkable. But he says that the effort to quantify the damages has its own benefits:

An America that asks what it owes its most vulnerable citizens is improved and humane. An America that looks away is ignoring not just the sins of the past but the sins of the present and the certain sins of the future. More important than any single check cut to any African American, the payment of reparations would represent America's maturation out of the childhood myth of its innocence into a wisdom worthy of its founders.

Coates has written a blog post, external that accompanies his article in which he explains how his views on reparations changed over the last four years, prompted in part by what he sees as the injustice of affirmative action programmes (which he says discriminate against Asian-Americans).

It's an interesting insight into the mind of a talented essayist.

On Friday I'll dig into some of the responses to Coates's piece.