Judges for sale?

- Published

- comments

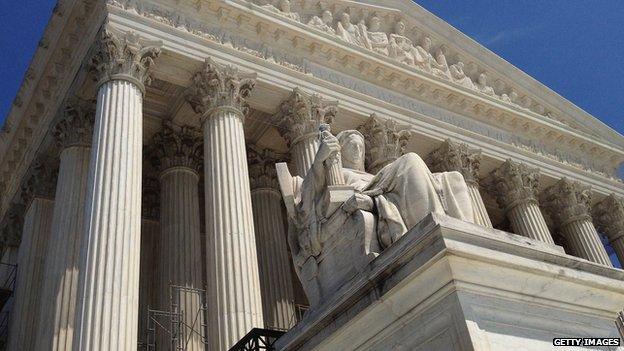

Citizen's United is back in America's courtrooms. But, this time, the famous US Supreme Court case isn't facing scrutiny, it's deciding who's sitting on the bench in the first place.

The ramifications of the 2010 Supreme Court decision, which deregulated campaign spending of organisations by labelling it free speech, are something Americans have got used to as cycle after cycle of congressional elections have got pricier and more antagonistic. But voters may have to get used to that same politicised atmosphere in their courtrooms.

States pick their judges in a variety of ways. Thirty-nine states opt to elect either some or all of their judges. Others use a merit system, in which there is a short list drawn up from which the local governor then chooses. That judge periodically faces retention elections.

In states where elections are taking place, however, they are starting to remind voters more of congressional elections, with the same money and harsh rhetoric.

"I don't think judges act like politicians because of the money," writes, external Jonathan Bernstein for Bloomberg View. "It's because anyone up for election is going to act like a politician."

He writes that he doesn't take issue with judges as political actors with some partisan ties, but he wants their connection to politics to be more indirect. Governors across the country should be appointing judges, he says. The system should encourage special interests to get involved in gubernatorial elections, not the justice system.

"It's one thing to elect a pro-business (or pro-labour) governor who then appoints pro-business judges; it's quite another for business groups (or unions) to become the primary electoral constituency of those judges," he writes.

Last election cycle $24m (£15m) was spent on judicial elections by outside groups, according to, external the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School.

Several recent US Supreme Court decisions have opened the door to more money being spent on judicial races

This election cycle, outside groups have spent nearly $2.1m on television adverts for state Supreme Court races in Illinois, Michigan, Montana, North Carolina and Ohio. Almost half of that was spent in the last week.

Defenders of moneyed judicial elections argue that the outside involvement is only matching the donations of activists, unions and trial lawyers, who have had free range to donate to judicial campaigns for years.

But the editors of the Washington Post point out, external that the results of those contributions have also been nasty. Essentially, they write, two wrongs don't make a right. They say that while regulating spending in these elections is a step in the right direction, the only way to get rid of the problem is to get rid of the elections entirely.

"A judge's job is not to serve a constituency, a particular donor or an ideology," they write. "It is to make a good-faith effort to apply the law."

The Atlantic's Norm Ornstein says, external that allowing multimillion-dollar campaigns undermines the idea of putting in place impartial and high-quality jurists. Beyond that, it reduces the judiciary in the public eye and destroys public trust in the system.

But the most important thing, he says, is that the stakes are high when the independent judiciary, the most important part of a functioning democratic political system, is threatened. This current system creates "an unhealthy dynamic of gratitude and dependency".

"The judges know that an adverse decision now will trigger a multimillion-dollar campaign against them the next time, both for retribution and to replace them with more friendly judges," he writes. "Will that affect some rulings? Of course."

A recent report, external from Emory University law professors Joanna Shephard and Michael S Kang seems to support that idea.

To avoid being labelled "soft on crime" when election season rolls around, the report says courts are more likely to rule against defendants in criminal appeals. Interest groups with political motivations or cases before the courts are using money to elect judges who are more likely to rule in their favour, Shephard and Kang write.

"Although their economic and political priorities are not necessarily criminal justice policy, these sophisticated groups understand that 'soft on crime' attack ads are often the best means of removing from office justices they oppose," they write.

Others see campaign contributions in judicial elections as necessary, however.

James Bopp, a prominent conservative lawyer who played a key role in the Citizens United case, said, external on a Washington, DC public radio programme that voters need a voice in deciding what kind of judge is put on the bench. Thanks to another court decision, he says, judge candidates are allowed to tell voters about their judicial views.

"They cannot pledge how to vote in a future case," he said. "That can be disciplined and would be wrong. But they can talk about their philosophy."

Bopp said that there should definitely be electoral restrictions, specifically around where and when judges are allowed to solicit campaign contributions. For instance, he said, they shouldn't be asking for money from litigants or lawyers who have cases pending in their courts. But they should be allowed to ask other people.

Others don't see money in elections as being that influential. New York Times columnist David Brooks says, external that there is mounting evidence that campaign spending doesn't lead to winning elections, because both candidates end up with enough cash in their coffers.

"We're now at a moment when a fire hose of money is trying to fill the same glasses of voters," he writes.

Money isn't the issue, he concludes, the quality of a candidate's message is.

Americans are used to a political landscape where money in politics is easily applied to congressional elections. They are used to belligerent attack adverts lambasting candidates for everything from voting records to their personal lives.

But are they used to hearing the same kind of information about their judges, who they very well may find themselves in front of one day?

If judges' jobs depend on the types of rulings they hand down, voters might have to get used to this landscape, where critics warn that the law may not be on their side, but on the side of the highest bidder.

(By Kierran Petersen)