A political correctness war that never really ended

- Published

- comments

New York magazine's Jonathan Chait took a 2x4 to the proverbial hornet's nest earlier this week when he penned a nearly 5,000-word essay, external under the provocative headline, "Not a very PC thing to say: How the language police are perverting liberalism".

For those not familiar with the term, PC refers to politically correct - a derogatory description coined in the 1990s to label those contending, in part, that language was a weapon used by the powerful to deny the interests of the oppressed. Although the term gained national awareness, external, the most ferocious debates occurred on college campuses and involved student speech codes and mandated gender inclusiveness.

The controversy died down in the new century, perhaps due to greater concerns in the national consciousness - terrorism and war, freedom and security. The debates, however, left their mark. Many of the journalists now reaching the higher levels of their profession, like Chait, had their educational experience defined by these often vitriolic episodes.

This writer, for instance, recalls that the most heated argument at his student newspaper - the one that fractured friendships and left some participants in tears - wasn't over abortion, the Gulf War or favoured political candidates. It was about replacing the word "freshman" with "first-year student" in the publication's style guide.

And now Chait has rubbed the scab off that particular cultural era and exposed a wound that still festers. He writes that the 20-year-old PC movement is returning with a vengeance - made all the worse by the roiling stew of opinion and outrage in social media.

Chait defines this new political correctness as mainly an internecine war among liberals, where "more radical members of the left attempt to regulate political discourse by defining opposing views as bigoted and illegitimate". It is at its heart, he says, illiberal and anti-free speech.

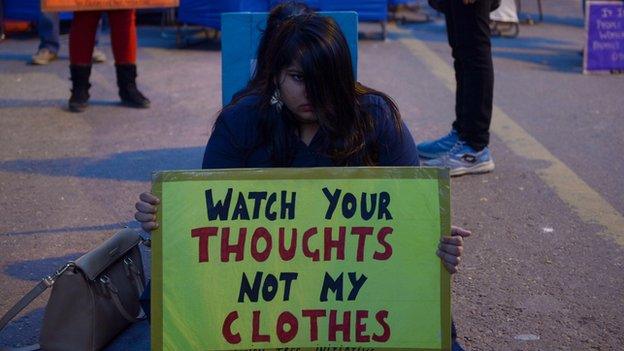

Chait says modern political correctness includes protesting controversial speakers

Among the examples he cites of modern-day PC extremism are calls for white males to "check their privilege"; trigger warnings on articles and college curricula; small slights called "microagressions" that, taken together, create a hostile environment for the unempowered; demands for inclusive language for trans-gendered persons; and protests that have prevented controversial lecturers from appearing on university campuses.

He points to a recent episode at Massachusetts' Mt Holyoke College, for instance, where a theatre group decided to end the annual performances of the play The Vagina Monologues - work that was celebrated as a beacon of feminist expression in the 1990s but now is considered by some progressive activists to "exclude women without vaginas".

"In a short period of time, the PC movement has assumed a towering presence in the psychic space of politically active people in general and the left in particular," he writes. And the end effect is that it is causing some writers to avoid controversial topics, lest they be subjected to online opprobrium that often crosses over to real-world threats.

In some ways, Chait seems like a flustered husband whose reaction when confronted by an angry wife is: "But think of all the good things I have done in the past".

"The historical record of American liberalism, which has extended social freedoms to blacks, Jews, gays and women, is glorious," he writes. "And that glory rests in its confidence in the ultimate power of reason, not coercion, to triumph."

Chait's critics say he is being "condescending and dismissive"

Given the internecine nature of the criticisms, however, Chait's essay was largely met with anger and mockery from those on his political left.

"Here is sad white man Jonathan Chait's essay about the difficulty of being a white man in the second age of 'political correctness,'" writes, external Gawker's Alex Pareene. He says Chait represents a comfortable, centre-left liberalism that, thanks to social media, has recently found itself being challenged by marginalised voices it used to be able to ignore.

"Now, in other words, writers of colour can be just as condescending and dismissive of Chait as he always was toward the left," Pareene writes. "And he hates it."

Amanda Marcotte on TalkingPointsMemo expands, external on what she sees as Chait's hypocrisy.

"Demanding that someone adopt more PC language to step around the sensitivities of liberals is unconscionable, but demanding that lefties on Twitter adopt a softened tone to step around the sensitivities of Jonathan Chait is just good sense," she writes.

Meanwhile, Vox's Amanda Taub dismisses, external Chait's essay as a collection of anecdotes in search of a creed.

Political correctness as he describes it doesn't, in fact, exist, she says. "Rather it's a sort of catch-all term we apply to people who ask for more sensitivity to a particular cause than we're willing to give - a way to dismiss issues as frivolous in order to justify ignoring them," she writes.

Others on the left express a certain amount of unease - both with Chait's piece and the response to it from their progressive compatriots. Social media have made it harder to express unpopular opinions "whether they have merit or not", writes, external the Nation's Michelle Goldberg, but it's a blade that cuts both ways.

"The price of bigotry is much higher, the ethical blind spots concealed by clubby consensus are much more easily exposed," she says. The danger, however, is that it creates a growing gap between what today's writers think and what they are willing say in public.

More than that, writes, external blogger Fredrick deBoer, this war within the progressive movement threatens to alienate would-be supporters who are criticised for their perceived lack of sensitivity.

"I want a left that can win, and there's no way I can have that when the actually-existing left sheds potential allies at an impossible rate," he writes. "But the prohibition against ever telling anyone to be friendlier and more forgiving is so powerful and calcified it's a permanent feature of today's progressivism."

Commentators on the right, of course, have little interest in a "left that can win", and their response has been mostly a combination of I-told-you-so's and concern-trolling, external for Chait, with whom they usually vehemently disagree.

Political correctness hasn't gone away, writes, external the National Review's Kevin D Williamson. "The difference is that it is now being used as a cudgel against white liberals such as Jonathan Chait, who had previously enjoyed a measure of immunity."

"Chait isn't arguing for taking an argument on its own merits; he's arguing for a liberals' exemption to the left's general hostility toward any unwelcome idea that comes from a speaker who checks any unapproved demographic boxes, the number of which - 'cisgendered', etc. - is growing in an appropriately cancerous fashion," he says.

Another conservative, the New York Times's Ross Douthat, argues, external that what the PC argument really boils down is that both sides think their counterparts are squelching their right to self-expression. And why? Because the tactic often works.

"There are contexts where making people afraid to disagree is actually a pretty successful ways of settling political and cultural arguments," he writes.

"You can usually get a good sense of just how powerful an idea is within a given political coalition by observing how vigorously ideological deviations are punished, which is why observers tend to argue (rightly!) that anti-tax activists have more power on the right than anti-abortion activists, and that social liberals have gained ground on the left at the expense of, say, union bosses or free trade critics, and so on."

The mistake almost everyone in the PC speech fight is making, he says, is in not admitting that they may, in fact, be misinformed.

"Like most systems of speech policing (which of course held sway in traditional societies as well) it excludes the possibility that those causes might be getting big things wrong, and thus it hurts the larger cause of truth," he writes.

Comedian/commentator John Hodgman, in a series of tweets, says, external that in the end the debate could be a constructive one.

"I'd never heard of cis-gender until it had been hurled at me as an invalidating insult on Twitter," he writes. "but I am glad I know it now. I am glad to give these issues thought. It enlarges me to be called out, even when I conclude the caller is a troll, and especially when it's by a person I respect."

On Friday, after telling the Daily Beast, external that the anger directed at his writing was like hot wax for a sadomasochist, Chait published a response, external on New York magazine's website.

He pushes back against accusations that he was personally hurt by the political correctness he describes.

"If there were a single sentence in the story expressing self-pity, it would be widely quoted by the critics, but no such line can be found," he writes. "The response partly reflects the PC culture's inability to evaluate arguments about identity as abstract arguments rather than reflections of the author's own identity."

He also says that the personal nature of the attacks shows that his critics are unwilling to actually defend the conduct he highlights: "My critics are not so much pro-PC as anti-anti-PC, which is not exactly the same thing."