Will the EU get a dream team?

- Published

Rivals for foreign policy chief: Italy's Federica Mogherini (left) and Bulgaria's Kristalina Georgieva

August is holiday time for the Brussels elite, but that has not stopped intense behind-the-scenes negotiation over candidates for the top EU jobs.

A special EU summit will take place on Saturday, aimed at deciding who will replace Herman Van Rompuy as European Council President and Catherine Ashton as EU foreign policy chief - officially the "EU High Representative".

The 28 member states failed to agree on candidates for those two top jobs on 16-17 July.

Now, the field appears to have narrowed quite a lot., external

They agreed earlier - controversially - to appoint Jean-Claude Juncker as president of the European Commission.

First of all, a big health warning. Don't underestimate the ability of EU leaders to spring surprises. In 2009 the emergence of Mr Van Rompuy and Baroness Ashton took most observers by surprise.

It is a very complicated balancing act, amid intense national rivalry for power and influence in the EU. If all 28 can be satisfied then the EU may have its dream team.

There is a trade-off between these jobs and the plum jobs in the European Commission, yet to be decided.

Here are some factors that will influence the leaders' choices when they meet in Brussels:

The Russia/Ukraine crisis has intensified over the summer - it will be a priority for the next EU foreign policy chief

There is strong pressure - from Jean-Claude Juncker and many MEPs - for more women to get prominent roles in the EU

The former communist states in Central and Eastern Europe say it is time for the EU to make a top appointment from their region

The centre-right bloc (European People's Party, or EPP) won the European elections in May but will not monopolise the top jobs - consensus is the way of EU politics, so the centre-left should get at least one top post

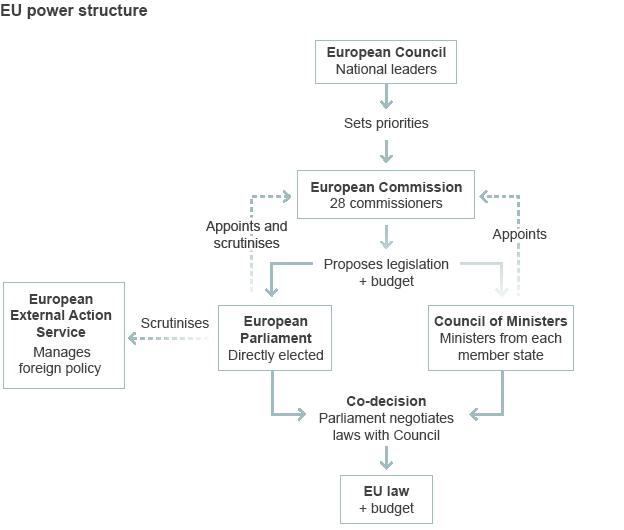

The European Council - that is, the government leaders - will want appointees who can work smoothly with the European Parliament, which can reject Commission candidates (and the foreign policy chief is also a Commission vice-president)

There is a preference for geographical balance, so that one region of Europe does not appear dominant

Contenders for European Council President: Denmark's Helle Thorning-Schmidt and Latvia's Valdis Dombrovskis

Last month Italy's centre-left Prime Minister Matteo Renzi could not persuade a majority in the Council to back his candidate for foreign policy chief - Federica Mogherini.

There was opposition from East European leaders who felt she was too friendly towards Russia. There were also widely reported concerns that she was new to the job as Italian foreign minister and relatively inexperienced in European politics.

But the director of the Carnegie Europe think-tank, Jan Techau,, external says there are signs that a deal has emerged to put her in the job after all.

"It looks like she'll be the one," he told the BBC. This month Mr Renzi managed to persuade other left-leaning governments to support Ms Mogherini - most significantly France, he said.

"Those who opposed her originally realised they had lost the fight, probably because they have been compensated elsewhere."

Ticking right boxes

This is where the trade-offs get very complicated. Poland has been pushing for its highly experienced foreign minister, Radek Sikorski, to get the job.

But what if Mr Juncker offers Poland the job of EU Energy Commissioner, or another powerful economic job instead? Poland - heavily reliant on fossil fuels - is keen to have more influence on EU energy policy. That could be enough for Mr Sikorski to be quietly dropped.

Sweden's Carl Bildt is another foreign policy big-hitter. But, like Mr Sikorski, he might be too ambitious and too outspoken on Russia for some EU leaders to stomach.

"As high representative you're essentially an employee of the member states. They always fear someone who sets an agenda - they don't want someone over-ambitious," Mr Techau says.

Jean-Claude Juncker needs more women candidates for his team if he is to get MEPs' approval

Next steps

September - Jean-Claude Juncker presents nominees for his new 28-member Commission and Parliament grills each one in turn (one from each member state)

October - Parliament votes on new Commission team

November - New Commission should take office, as should new EU foreign policy chief and new European Council president.

Both top jobs could go to women. Two names are often mentioned by Brussels-watchers: Helle Thorning-Schmidt (Danish Prime Minister, centre-left) and Kristalina Georgieva (Commissioner for Humanitarian Aid, centre-right Bulgarian).

Ms Thorning-Schmidt has long been seen as a favourite to replace Mr Van Rompuy as European Council President.

An analyst at the Open Europe think-tank, external, Pawel Swidlicki, said Ms Mogherini might still be too controversial to get the necessary support.

Ms Georgieva as foreign policy chief would tick the East European box, he said, while Ms Thorning-Schmidt would be the counter-balancing centre-left leader as council president.

"The rest of the college of commissioners looks very male-heavy, so having two women appointed could persuade the European Parliament," he told the BBC.

But another strong contender for Mr Van Rompuy's job is Latvia's ex-Prime Minister, Valdis Dombrovskis, Mr Techau argues. He has the advantage of being both an East European and from a eurozone country.

The leaders will try to agree by consensus, without taking a formal vote. The vote which resulted in Mr Juncker's appointment was unusual - it happened at the UK's insistence.

- Published26 August 2014

- Published15 July 2014

- Published1 July 2014

- Published15 July 2014

- Published1 July 2014

- Published30 June 2014