Romania anti-sleaze drive reaches elite

- Published

Former minister Elena Udrea, now an MP, was taken to court on 11 February

The TV crews wait outside Romania's National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA) in Bucharest to see who will be next.

The long faces emerging from the building resemble a soap opera procession of the once high and mighty.

Former government ministers, media moguls, judges, prosecutors, and even former President Traian Basescu's favourite, Elena Udrea - dubbed "the president's blonde" - are all under investigation.

Ms Udrea, a former minister of tourism and former presidential candidate, was arrested last week. She is currently an MP.

The DNA's latest targets include Social Democrat Prime Minister Victor Ponta's mother, sister and his brother-in-law Iulian Hertanu.

Eight years after joining the EU, and 13 years after the DNA was set up, Romania seems to be finally getting serious with organised crime - and winning praise from the European Commission., external

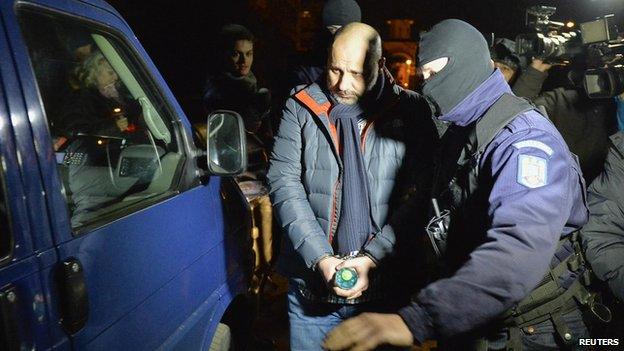

Iulian Hertanu, brother-in-law of the prime minister, was detained in Ploiesti

EU pressure

"Romania is on the right course and needs to stick to it," said Commission First Vice-President Frans Timmermans last month, commenting on the latest EU report on Romania's battle with corruption.

"Tackling corruption remains the biggest challenge and the biggest priority."

The EU's Co-operation and Verification Mechanism was set up in 2007 to monitor judicial reform and the fight against corruption in Romania and Bulgaria. Positive reports are crucial for Romania to be allowed into the EU's open-border regime, the nations in the Schengen group.

Last year alone, 1,138 leading public figures, including top politicians, businessmen, judges and prosecutors, were convicted by the DNA, whose crackdown is being led by chief prosecutor Laura Kovesi - a rate of more than four a day (excluding holidays). So what has changed in Romania?

"In just three years, both big parties - the Orange [Democratic Liberals] and the Reds [Social Democrats] - have been defeated in elections," says analyst Alina Mungiu-Pippidi. She is president of the Romanian Academic Society, external, an independent policy institute.

The result is that what she calls the "trans-party mafia" that used to run the country, hand out procurement deals involving huge sums of EU money, dodge tax and buy off prosecutors and judges is in disarray.

Prosecutors at Romania's DNA are going after some big fish now

Laura Kovesi is spearheading the DNA's crackdown

Under surveillance

Equally important, she says, is the character of Klaus Iohannis, elected Romanian president last November. As a political outsider, he is not a signatory of the secret deals between the main parties that have plagued Romanian politics for 25 years.

A typical DNA conviction was that of Monica Ridzi, 37, the former sports and youth minister. She was sentenced to five years in prison for abuse of her position, by spending $800,000 (£518,000) of state funds on youth concerts at inflated prices, using her favourite companies. The proceeds were allegedly divided between herself and her party.

The DNA relies on the secret services for wiretaps of senior figures. "Until now, the services were rather selective about who they investigated. But no longer," says Ms Mungiu-Pippidi.

- Published18 December 2024

- Published3 February 2014

- Published13 September 2010