Portugal's left alliance flexes muscle and prepares for power

- Published

Portuguese PM Pedro Passos Coelho (right) and his deputy, Paulo Portas, presented their government's programme before a parliament dominated by the left

It was in power for under a fortnight, and Portugal's right-of-centre administration, led by Pedro Passos Coelho, had barely been able to present its programme for government before it was voted out by a Socialist-led alliance.

Mr Coelho had emphasised the need for budgetary rigour, almost a year-and-a-half after the country exited a eurozone bailout. But his minority government did not have the numbers to push the plan through parliament.

Even as Tuesday's debate was still going on, the Socialists' leader, Antonio Costa was signing agreements with three other parties - the radical Left Bloc, the Communist Party, and the Greens.

Together, these parties have a majority in parliament that could, in the words of the Socialist leader, Antonio Costa, "turn the page on austerity".

"Today we already know the answers: the Left Bloc, PCP (Communists) and Greens guarantee conditions of stable governance over the [full] parliament," he told parliament.

And the motion put forward by Mr Costa's party gave an idea of the balance he wanted to strike.

Socialist leader Antonio Costa (R) signed a deal with three other parties before the vote in parliament

While it committed to a "strategy of consolidating the public accounts", the Socialists said economic policy should be "based on growth and employment and increasing families' incomes".

There would be a move away from a mainly low-wage economy while focusing on public healthcare, education and social security.

The Socialists have also dropped some more market-oriented proposals in their election manifesto, such as making it easier to hire and fire employees.

The deals secured by the Socialist Party may provide it with some breathing space, while not shielding it indefinitely from attacks from the left, particularly Portugal's largest trade union federation, the CGTP, which has close links with the Communist Party.

"Rome wasn't built in a day," the CGTP's general secretary, Armenio Carlos, told foreign journalists on Monday.

Protesters outside parliament called for the fall of the centre-right minority government

"The Socialist programme has positive aspects but in our opinion it needs to go further," Mr Carlos said.

He cited areas such as collective bargaining over pay and conditions, where legislative changes in the last parliament had the effect of slashing the number of workers covered by such contracts. The CGTP wants that reversed.

"Our experience with previous Socialist governments wasn't good," Mr Carlos said. "This is a process with various phases... but it can't take forever."

Demands by the Socialists' own supporters, many of whom work in the public sector, could also push up public spending.

While the party's new programme foresees a public sector budget deficit next year of equivalent to 2.8% of gross domestic product - slightly less than that projected by the current government - independent economists are sceptical.

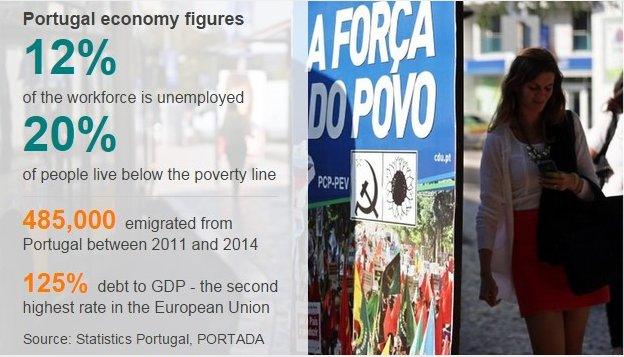

Portugal economy figures

12%

of the workforce is unemployed

20%

of people live below the poverty line

-

485,000 emigrated from Portugal between 2011 and 2014

-

125% debt to GDP - the second highest rate in the European Union

Even though the minority government has fallen, President Anibal Cavaco Silva is not necessarily obliged to turn next to the Socialist Party leader.

A former leader of Mr Coelho's party, President Cavaco Silva has since the election made public his reservations about swearing in any government that must rely on forces - such as the Left Bloc and Communists - that oppose Portugal's key international commitments, such as European Union rules on budget deficits and membership of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato).

The president could ask the incumbents to stay on as a caretaker administration - but that would fly in the face of other concerns that he has expressed about the need for a firm hand on the tiller.

Antonio Costa (left) may be asked by President Anibal Cavaco Silva to form a government - but not necessarily

A caretaker government could not table a budget, meaning that a range of measures that currently dampen state spending would automatically fall away on 1 January.

Under Portugal's constitution, the president may not dissolve a new parliament in its first six months.

Mr Cavaco Silva's own term comes to an end in March, but even if his successor dissolves parliament at the earliest opportunity, in April, 60 days' notice is needed for an election, so Portugal would be without a budget until June or even July.

The one thing that Portugal's constitution clearly obliges the president to do if the government falls is to consult all parties with seats in parliament.

That will be the chance for the left-of-centre parties to press him to allow the formation of a Socialist government with an unprecedented support base that includes avowed Marxists.

- Published7 November 2015

- Published22 October 2015

- Published5 October 2015