EU-Turkey migrant deal: A Herculean task

- Published

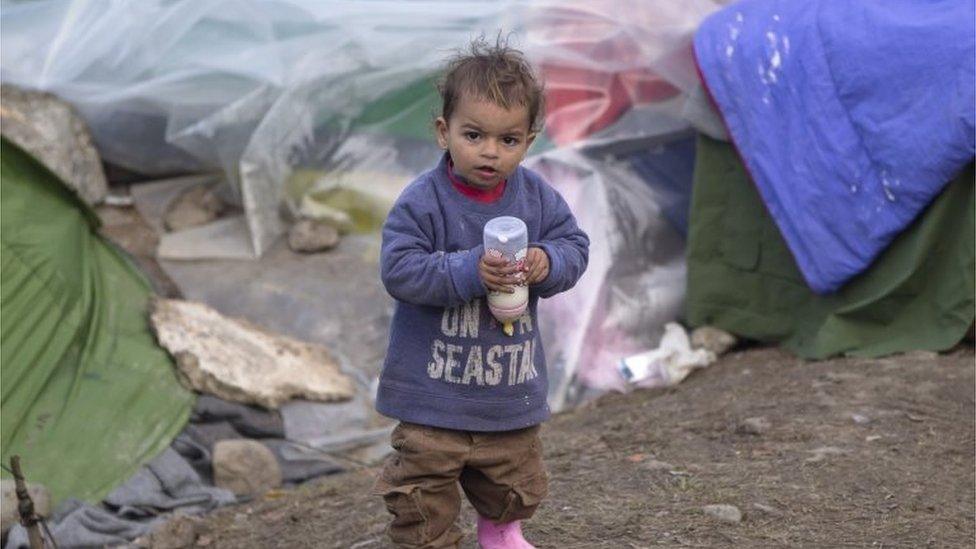

Thousands of migrants are currently living in a makeshift camp in Idomeni, Greece, in squalid conditions

A deal has been done, but - in the words of Jean-Claude Juncker - implementing it will be a Herculean task.

"It is the biggest challenge the EU has ever faced," he said.

It was a sober assessment from the president of the European Commission, which reflects the fact that this is a throw of the dice, a gamble based on deterrence which could well fail.

Scepticism hangs heavy in the air about a host of legal issues, and about whether the agreement can actually work in practice.

The idea at the heart of the deal - sending virtually all irregular migrants back to Turkey from the Greek islands - is the most controversial.

European leaders insist that everything will be in compliance with the law.

"It excludes any kind of collective expulsions," emphasised European Council President Donald Tusk.

But Amnesty International has accused the EU of "turning its back on a global refugee crisis, and wilfully ignoring its international obligations".

The UN refugee agency (UNHCR) will take part in the scheme, but it is clearly uncomfortable with what has been agreed.

'Irreversible momentum'

There were heated discussions in Brussels as EU leaders and Turkey tried to finalise the deal

And the scale of what will need to be done - and done quickly - on the Greek islands is staggering:

Thousands of European officials will have to be dispatched to the islands within a matter of weeks

The "hot-spot" reception areas which have been set up over the last few months will have to be turned into detention centres

Tribunals will have to be set up to ensure that every refugee and migrant has their case heard on an individual basis, including the right of appeal

Turkish police officers will have to go to the islands to co-operate with the Greek police after decades of trying to ignore each other

"I have no illusions that what we agreed today will be accompanied by further setbacks," admitted Angela Merkel.

"There are big legal challenges that we must now overcome."

The German chancellor argued, though, that the agreement has "irreversible momentum". Others think it could quite easily fall apart.

Even if - with massive help from its allies - Greece manages to get things up and running, the Turkish asylum system will remain another focus of controversy.

Several EU countries had tried to insist that Turkey should change its laws so that migrants from all countries can receive formal international protection there under the Geneva Convention.

But the Turkish authorities refused to do that. All there is in the summit statement is a vague commitment that "everyone will be protected in accordance with the relevant international standards".

"How," asked one legal official involved in refugee issues, "will this be implemented, monitored or enforced?"

'Fingers crossed'

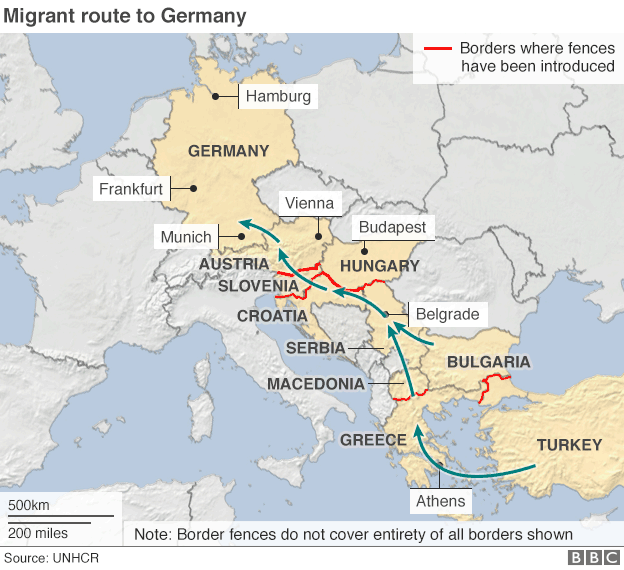

Many thousands of refugees try to get to Greece each year by crossing the sea from Turkey

The response from the European Union - and from Turkey - is that something had to be done to limit irregular migration, and that this amounts to the best deal possible in difficult circumstances.

From Sunday virtually all migrants arriving in the Greek islands will be eligible to be sent back to Turkey.

Returns are expected to begin in early April. For each Syrian migrant sent back, another Syrian will be resettled from a refugee camp in Turkey directly to the EU.

The resettlement programme will, at the insistence of Turkey, begin on the same day.

Germany will take the lion's share of Syrians, and participation from other EU countries will be on a voluntary basis.

But if thousands of people continue to arrive in Greece, the plan will fall apart. Everyone knows it.

"It's time to cross the fingers, work hard, and hope for the best," one EU official acknowledged. "There is a huge amount still to be done."

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.