Who, what, why: How unhealthy is two years indoors?

- Published

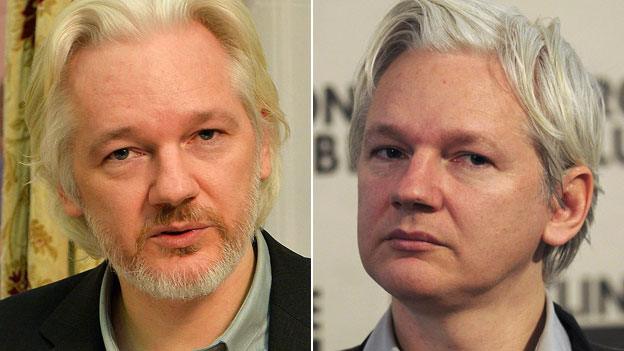

Julian Assange in August 2014 and in February 2012

Julian Assange says he will leave the Ecuadorean Embassy in London "soon". There's been speculation he is suffering from illness, so what is the potential health impact of two years indoors, asks Tom de Castella.

The Wikileaks founder took refuge in the embassy in June 2012 to avoid extradition to Sweden to face questioning over alleged sex assaults. He faces arrest if he leaves the building.

Assange told a press conference that he had no access to outside areas. Even healthy people would have difficulty living inside for so long, he said. Claiming he would be out "soon", he was vague on when or why.

Media reports have suggested he needs treatment for a range of health problems - arrhythmia, high blood pressure and a chronic cough.

The biggest implication for physical health of being inside for so long is vitamin D deficiency, says Sarah Jarvis, doctor for the BBC's One Show. About 85-90% of people's vitamin D comes from sunshine. Dozens of conditions have been associated with low vitamin D levels, from depression and aches and pains to osteoporosis and heart disease.

Vitamin D tablets don't seem to have much effect, says Simon Griffin, professor of general practice at Cambridge University. A sunbed or UV lamp would work but over two years this would be inadvisable - they are linked with melanoma, a form of skin cancer. And Assange has already spoken of a "boiled lobster" moment from a sunlamp, external.

It's unlikely two years inside would damage the body greatly if someone took action to make sure they were getting some daylight, exercise and eating a healthy diet, says Griffin. Air conditioning is unlikely to harm Assange. The most likely harm would be a flattening of mood, Griffin says. Sunlight makes people feel happier. There is a balcony at the embassy - Assange has occasionally addressed supporters from it. Even just exposing face and forearms to the sun regularly would help avoid feeling down, Griffin says.

One thing that's impossible to gauge is Assange's mental state. Maintaining it is all about how you perceive your situation, says clinical psychologist Linda Blair. When he first arrived Assange had evaded capture. He might have felt euphoric. But two years on, he is still there. "It's about an attitude really. It makes us very aggressive when we are denied our freedom."

Some prisoners of war have managed to play games and celebrate the fact they are still alive in terrible conditions, Blair says. "You don't have to feel trapped. Feeling you have control is critical."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.