Did King John actually 'sign' Magna Carta?

- Published

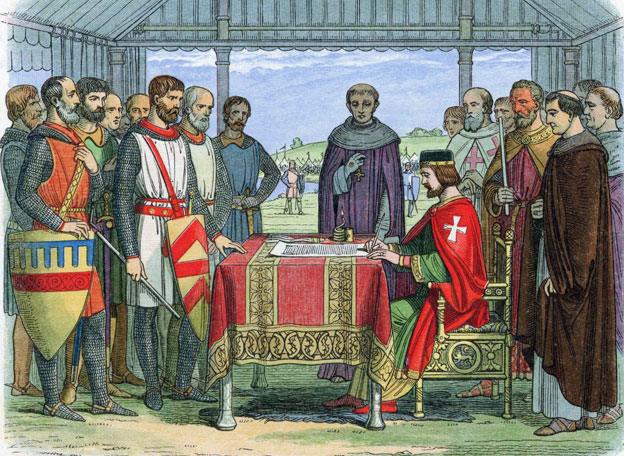

The Royal Mint has been criticised for featuring a picture of King John signing Magna Carta with a quill on a coin celebrating its 800th anniversary. A wax seal was actually used, but does the mistake really matter, asks Justin Parkinson?

The £2 coin shows King John holding Magna Carta in one hand and a large quill in another. The meaning is obvious - he signed it.

Actually, he didn't. John, like other medieval monarchs, used the Great Seal to put his name to the document, making concessions to England's barons in 1215, following years of arguments over royal power.

The Royal Mint has been accused of making a "schoolboy error". Historian Marc Morris stated that medieval kings "did not authenticate documents by signing them" but "by sealing them".

The Mint has defended itself by saying the scene shown on the coin is not meant to give a "literal account of what actually occurred".

No quill was used, but was the Magna Carta still "signed" in a sense? The Oxford English Dictionary defines the verb "to sign" in this way: "To put a seal upon (a letter or document) as a means of identification or authentication; to stamp with a seal or signet; to cover with a seal." The first use the OED records of the verb used in this way was by King John's son Henry III, saying a document was "sened wiþ vre seel (signed with our seal)".

It wasn't quite like this

So, the idea of signing something predated our more narrow modern sense of a person writing their name or something else to denote their consent - the autograph signature.

Is criticism of the Royal Mint fair? "I think it's pretty harsh," says Jane Caplan, professor of modern history at Oxford University. "The story is pretty complicated and it's not surprising that people make mistakes."

The wording of Magna Carta, a verbal agreement between the king and the barons, was written down later and the seal added by officials. So he didn't seal it himself either. The contents of the copies made were to be read out in public in what was still more of an oral official culture than our own.

The wax seal helped validate the understanding that Magna Carta was the King's true will. "The seal was the conventional way of authenticating a document at that time," says Claire Breay, medieval manuscripts curator at the British Library.

It was not "signed" according to the conventional modern usage of the word, but 1215 was not the modern world.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.