What would Wittgenstein say about that dress?

- Published

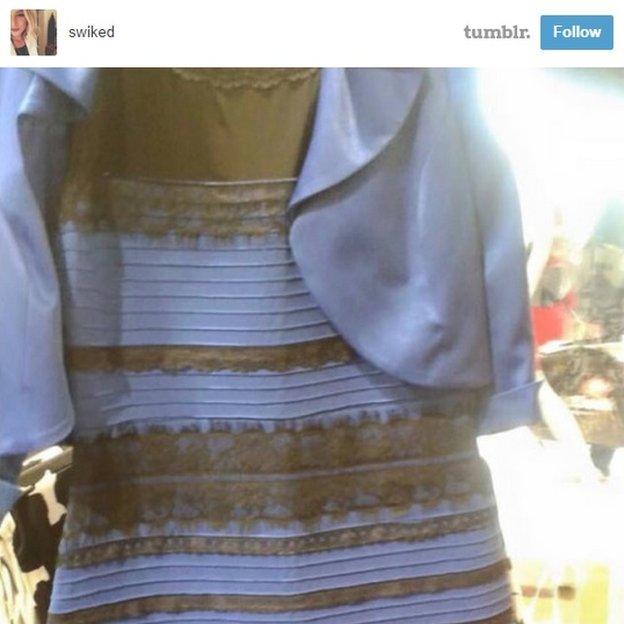

"What colour is that dress?" The question has been fascinating people all around the world, including Prof Barry C Smith of the University of London's Institute of Philosophy.

We all assume that we see what's before our eyes, and if we have normal colour vision we should be able to tell what colour the dress is. And yet we've just discovered that the world of observers divides into two groups - those who see the dress as white and gold, and those who see it as blue and black, or blue and olive green. They know they are looking at the same image and that it isn't changing, so why is there such marked disagreement about how the dress looks?

Could it be that we all see the world very differently? Have we just discovered that there is no such thing as the true colour of things? Is colour just in the eye of the beholder? That may be a tempting conclusion, but the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein would have resisted it. He was famous for pointing out errors in our everyday thinking. So when told by his pupil, Elizabeth Anscombe, that it was easy to understand why people thought the sun went round the earth, Wittgenstein asked, "Why would they think that?" "Well," said Anscombe, "it looks that way." To which Wittgenstein replied, "And how would it look if the earth went round the sun?" The answer, of course, would be: "Just the same."

So how might Wittgenstein have reacted to our query about the true colour of the dress - or to the fact that people who up until now have agreed about the colours of all sorts of things suddenly see the dress so differently? After all, the same wavelengths of light are entering the retinas of each observer. How can it look white and gold to some and blue and black or olive green to others?

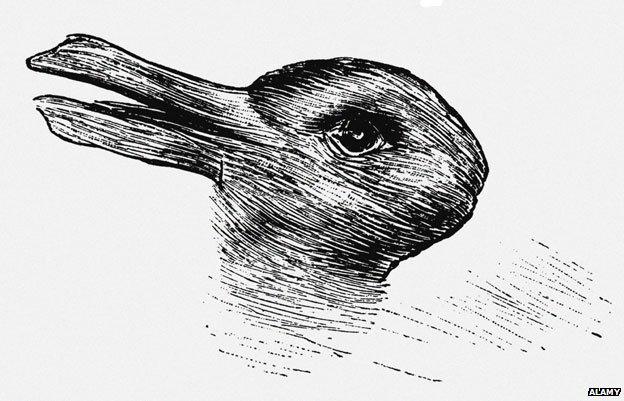

Wittgenstein might have pointed us to Joseph Jastrow's duck-rabbit figure.

When you look at the drawing, without it changing, it is possible to see it either as a duck or a rabbit. You can't see both animals at once but you switch from one to the other. Wittgenstein called this "aspect-switching" since you see one aspect when you notice the long shapes as rabbit's ears, and another when you see them as a duck's bill. The same object can look completely different when we attend to parts of the drawing and think of them as a duck's bill or as a rabbit's ears.

So is it the same with the dress? There are good reasons to doubt it. Not many people report being able to switch between the blue-black/olive and the white-gold colours. Instead, it is looking at the image on different monitors, or in different lighting conditions that induces a change.

And there's the clue. Just as in the case of the duck-rabbit figure, it's not just what we see but how we think about what we see that influences how something looks; and most people who see the dress as white and gold say the white colour of the dress is being tinted by a blue-ish light. In fact, what they claim to see is how a white dress looks in slightly blue lighting.

For the rest of us - whose visual systems don't wash out the blue when it is illuminated by blue lighting - we don't think of it as parts of a white dress reflecting blue light but as a parts of a blue dress in white light. Between what we all see and how we judge what we see comes the thought, and thoughts make us look at the same things differently.

In the case of the dress, both ways of viewing the colour in the image are illusory but unlike Wittgenstein's cases of aspect-switching, it's not a shift of attention or a difference in background ideology that separates the two ways of viewing the dress. It's a categorical difference in the ways our visual systems interpret colours in the world - a difference we have only just discovered.

Wittgenstein had thought of using a sentence from Shakespeare's King Lear, "I'll teach you differences" as a motto for his Philosophical Investigations. This would be a perfect example.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.