The Vocabularist: Where did the word 'king' come from?

- Published

Leicester: Royal interments are not common, even in England

The excitement over Richard III's body has emphasised the history and mystique of kingship - and the word king has an allure which echoes its ancient meaning "son of the kin".

Even a monarch whom tradition calls a villain and who was certainly short-lived and unsuccessful should get an interment "fit for a king," writers have said, external - and priests have talked of the nation "taking Richard III to its heart".

The idea that kings are not mere super-politicians but also embody the spirit of their people - and so deserve reverence - finds an echo in the origin of the word.

The Anglo-Saxon "cyning" from cyn or kin, and -ing meaning "son of" evokes images of long-gone tribes choosing as leader a favoured son who is mystically representative of their common identity.

Similar words appear in all other Germanic languages, and from the earliest times have been accepted as the same as the Latin rex.

Rex has its roots in the common ancestor of most European languages, associated with stretching, thus keeping straight (di-rect, cor-rect) and then governing. Words related to rex appear in Germanic tongues too, such as our bishop-ric, and the German Koenigreich (kingdom).

King has always meant male leaders and reflected a spectrum of actual power - from the Great King of Persia whom the Greeks called THE King, down to "I'm the King of the castle".

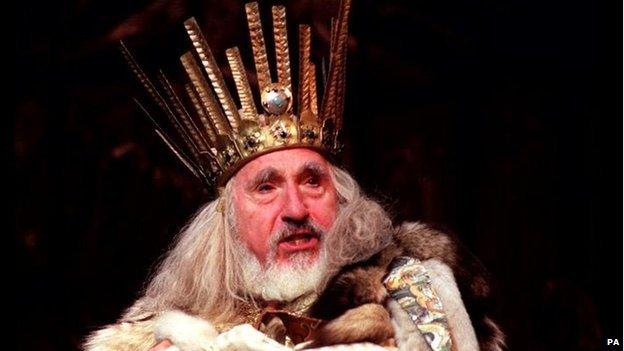

Nigel Hawthorne as King Lear: Shakespeare endlessly explored the glories and woes of kings

The word king is important in religion. There's a powerful mythology that kings must die to ensure the welfare of their people. It's chronicled in Sir James Frazer's "Golden Bough", external, which contains many examples of beliefs that a king "must be killed as soon as he shows symptoms that his powers are beginning to fail".

But no-one explored kingship as ruthlessly as Richard III's chief publicity agent, William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare wrote again and again of kings' powers to be comic and heroic (Henry V) and scheming and wicked (Claudius) and magnificently, to combine great power with human weakness (Macbeth, Lear) - but left poor Richard bidden by the ghosts of those he wronged to "die in terror of thy guiltiness".

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.