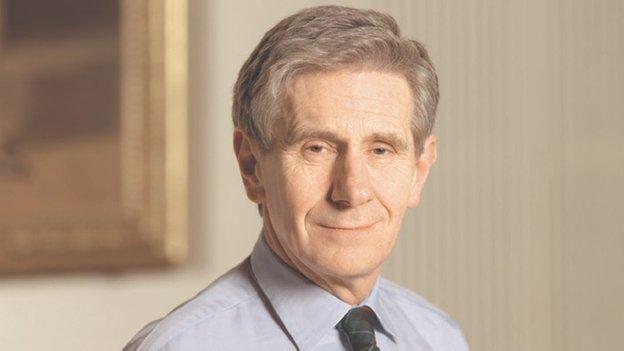

Former HBOS chairman on how clinical depression hit him

- Published

The former chairman of HBOS, Lord Stevenson, says that, despite having made many big business decisions, the only really brave decision he has taken was telling people about his depression.

Lord Stevenson of Coddenham has had demanding roles in the past such as chairman of Pearson, and was chastised by the Banking Standards Commission over the 2008 collapse of HBOS, but says that though business can be very difficult, depression is the worst thing he has experienced.

"It was completely off-field and unexpected," says Lord Stevenson about his first bout of clinical depression almost 20 years ago.

"We go as a family to our cottage in Suffolk for most of August. I was driving down and the sun was out and it was wonderful. Next morning I woke up with literally a pain in my stomach and it turned into what is known to be anxiety."

Within a week of experiencing the physical pain, he was diagnosed with clinical depression.

"There was no apparent reason for it," he says. "Everything in my life was lovely."

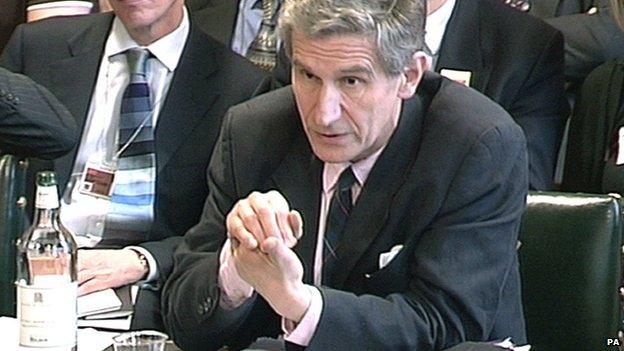

Lord Stevenson was chairman of HBOS between 2001 and 2009 and was at the helm during its "credit crunch" collapse. Much blame was attributed to him and other directors of the company and in 2009 he faced a Treasury Select Committee where he was closely questioned about decisions that were made.

But though this was a difficult time for him he says he did not suffer an episode of clinical depression during this period and is clear to emphasise the difference, for him, between mental illness and what might be described as unhappiness.

"[That time was] perfectly horrible and still is," he says. "There were sleepless nights and feelings of anxiety but it is not the same as clinical depression. Clinical depression is an illness. Unhappiness, whether because of something that has gone wrong at work or because someone has died or divorced is quite different.

"When I have clinical depression I get no pleasure out of any of the things I [normally] get pleasure out of. I lose all self-confidence and I never believe I can get out of it."

He says it is "presumptive" to think there must be an external factor - such as work - that causes an episode of depression.

"The big question is what does cause [these episodes]," he says. "The truth is we don't really know." He puts it down to a combination of biological and environmental factors.

But the mental health charity Mind says work can be the root of mental health problems. Recent research from the charity found it was the biggest cause of stress in people's lives with one in three people describing it as very, or quite, stressful.

Lord Stevenson faced a Treasury Select Committee about the collapse of HBOS

Mind's chief executive Paul Farmer says: "Too often people don't speak up, fearing a negative response, which means they don't get access to timely support."

They also believe that there is a much closer link between unhappiness and depression noting that feeling low for a few weeks or recurring unhappiness could be a sign of depression.

Lord Stevenson estimates that in the top hundred companies a quarter of those running them have, or have had, mental illnesses, but few have openly acknowledged it.

He says people with certain mental dispositions are well suited to leadership roles.

"I have a saying that a lot of leaders are anxiety driven little shits," Lord Stevenson says. "Anxiety and the feeling of a need to prove things are very strong, the higher you get up the 'greasy pole' the greater the concentrations of certain kinds of illness."

Emma Mamo, Head of Workplace Wellbeing at the Mind charity, agrees that people with mental illnesses can make good leaders - as long as mental wellbeing is monitored.

"It's a common misconception that having a mental health problem is a sign of personal weakness," she says. "In fact, living with or recovering from a mental health problem can help people build up a variety of skills, such as resilience, self-awareness and empathy, that lend themselves well to effectively managing a workforce."

Lord Stevenson's experiences can be heard on The Bottom Line on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday 3 July at 20:30. It will be available soon after on the iPlayer.

Follow @BBCOuch, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external, and listen to our monthly talk show