The learning disabled who live miles from family

- Published

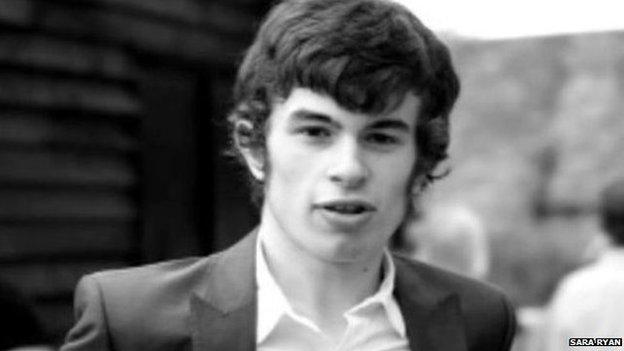

Connor Sparrowhawk died in a care centre in 2013

People with learning disabilities can find themselves in care hundreds of miles from home and their loved ones, with little or no choice on how they should be looked after, campaigners say. Now there are calls for a change in the law to allow disabled people and their families the statutory right to decide what kind of care and treatment is best.

Sara Ryan's son Connor Sparrowhawk was 18 when he died during a stay at an NHS in-patient unit for people with learning difficulties in Headington, Oxfordshire. He had autism, epilepsy and a learning disability and had been assessed there for four months at the time of his death.

Angry that he had died in a place meant to keep him safe, Ryan started a social media campaign under the name Justice for LB (Connor's nickname was Laughing Boy) which has gathered a huge amount of support and funding towards legal representation for an inquest into her son's death- a campaign which is ongoing.

Using that same support, another more ambitious campaign has emerged which is attempting to initiate a private members' bill - the LB Bill - to try and put the choices of disabled people and their families at the heart of the decision-making process.

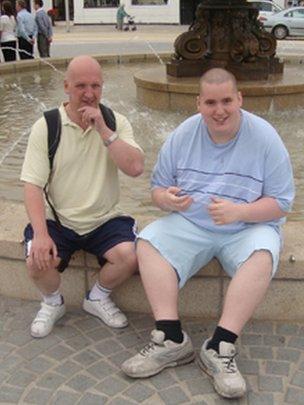

The idea began with blogger Mark Neary who says: "I think we should be starting with the fundamental principle that a learning disabled person should be living in their own home, whether that be with their family, on their own with support, in a small group. If the state then thinks otherwise they should have to prove their case before a court." Such issues are close to home for Neary whose autistic son Steven Neary was unlawfully placed in a care unit for a year in 2009. The judge concluded that the council's use of a "deprivation of liberty" order unlawfully deprived Stephen of his freedom.

Steven Neary (right) was placed in care away from his father for a year

Lawyer and disability campaigner Steve Broach quickly got in touch with Mark Neary to offer his support to the LB Bill. He says that their proposition is in agreement with one of the fundamentals in Article 19 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the right to independent living.

He argues that at present, in the UK system, ratification does not give disabled people an enforceable right to independent living - because for rights in international treaties to become real here, they have to be "incorporated" into the law through an Act of Parliament.

"What we are hoping for," he says, "is that we will make this into such a big issue that MPs cannot ignore it. We are struggling with a huge social question. Why are people with learning disabilities being put in these facilities? This campaign feels exciting, it's incredibly authentic and feels like it may be a tipping point." But he is keen to be realistic. "It's very early days. We need to spend the next few months really figuring out what should go in the Bill."

Connor Sparrowhawk's death reignited debate about assessment and treatment units. In 2011 abuse of patients with learning disabilities at Winterbourne View, a privately run unit, was exposed by BBC's Panorama. In the wake of the scandal, the Department of Health and a wide range of groups including NHS England, and the Local Government Association, signed a concordat that pledged to "support everyone inappropriately placed in hospital to move to community-based support as quickly as possible and no later than 1 June 2014."

Earlier this year the Care Services Minister Norman Lamb said that the effort to move people with learning disabilities out of hospital had been an "abject failure". The June target date came and went and disabled people and their families are still waiting.

One such family is that of Josh Wills, a 13-year-old with severe autism. His father Phil Wills says his son self harms so badly that his life is in danger and so needs specialist care. Until he was eleven Josh lived in Cornwall with his family where his father says he was content - he used to run on the dunes, skip in the park with his friend and visit the shops.

When the teenager's self harming increased in July 2012 it was decided, by the local NHS commissioning group, that he needed to be placed in a unit. The unit that was chosen was in Birmingham, 260 miles away from home. His parents, Phil Wills and Sarah Pedley, agreed because there was nothing suitable locally and it would be just for a six month assessment period to give everyone an understanding of the support and services Josh needed.

Almost two years later, Josh is still in Birmingham - a five-hour trip for his family. His self-harming has become so bad that he bit off part of his tongue and has recently needed surgery on an infected hand.

Josh Wills' parents visit their son in Birmingham on alternate weekends

Josh's father is keen to stress that the care his son has received is excellent but the problem for them is that Cornwall is his home where he's comfortable and where his family are.

"People ask why I don't move to Birmingham," he says, "but that is taking away Josh's chance to come home."

Last week the Wills family received good news when Care Minister Norman Lamb summoned them to Westminster to tell them that he will ensure Josh returns to his community.

Unable to give a definitive date, Lamb says of the situation: "People with complex needs deserve the best possible care, in their own communities with the right support. I have shared the concern and frustrations of Josh's parents. I am pleased that progress is now being made."

Now it has announced that a new steering group will prepare a guide on care for people with learning disabilities which will be released in October. Headed up by Sir Stephen Bubb, chief executive of the Charity leaders' organisation, Acevo, NHS England announced that the group will also include healthcare, charity and voluntary sectors, as well as people with learning disabilities and their families. Campaigners including Broach and Neary are, however, concerned that there has been little information about the latter so far.

Claire Dyer has told her family she does not want to be far away from them

But Sir Stephen wants everyone to join forces on this issue. "People with learning disabilities, communities, charities and social enterprises must come together to realise this vision - and I hope as many people as possible will share their knowledge, expertise and experience to shape what we do and how we do it."

Jan Tregelles, chief executive of Mencap, who sits on the steering groups adds it will produce a blueprint for developing the services needed to ensure that people with a learning disability can be well supported in their communities. "Ultimately this will end the unacceptable culture of long term placements in inpatient units, where people are at significant risk of abuse and neglect," she says.

Disabled campaigners are keen that decisions are made soon. A court hearing on Friday will decide whether or not a 20-year-old autistic woman, Claire Dyer, will be moved to a specialist unit in Brighton, 240 miles from her home. The campaigners are hopeful that if their Bill is successful it could signal the end of such long-distance care for people with learning difficulties and lead to significantly improved community care.

Follow @BBCOuch, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external, and listen to our monthly talk show