How easy is it for the limbless to get a bionic arm or leg?

- Published

Last week a woman who was born without a hand, showcased her new bionic arm - said to be the most lifelike one yet. But bionics can cost up to £100,000 and aren't an option for everyone - so what do other people do?

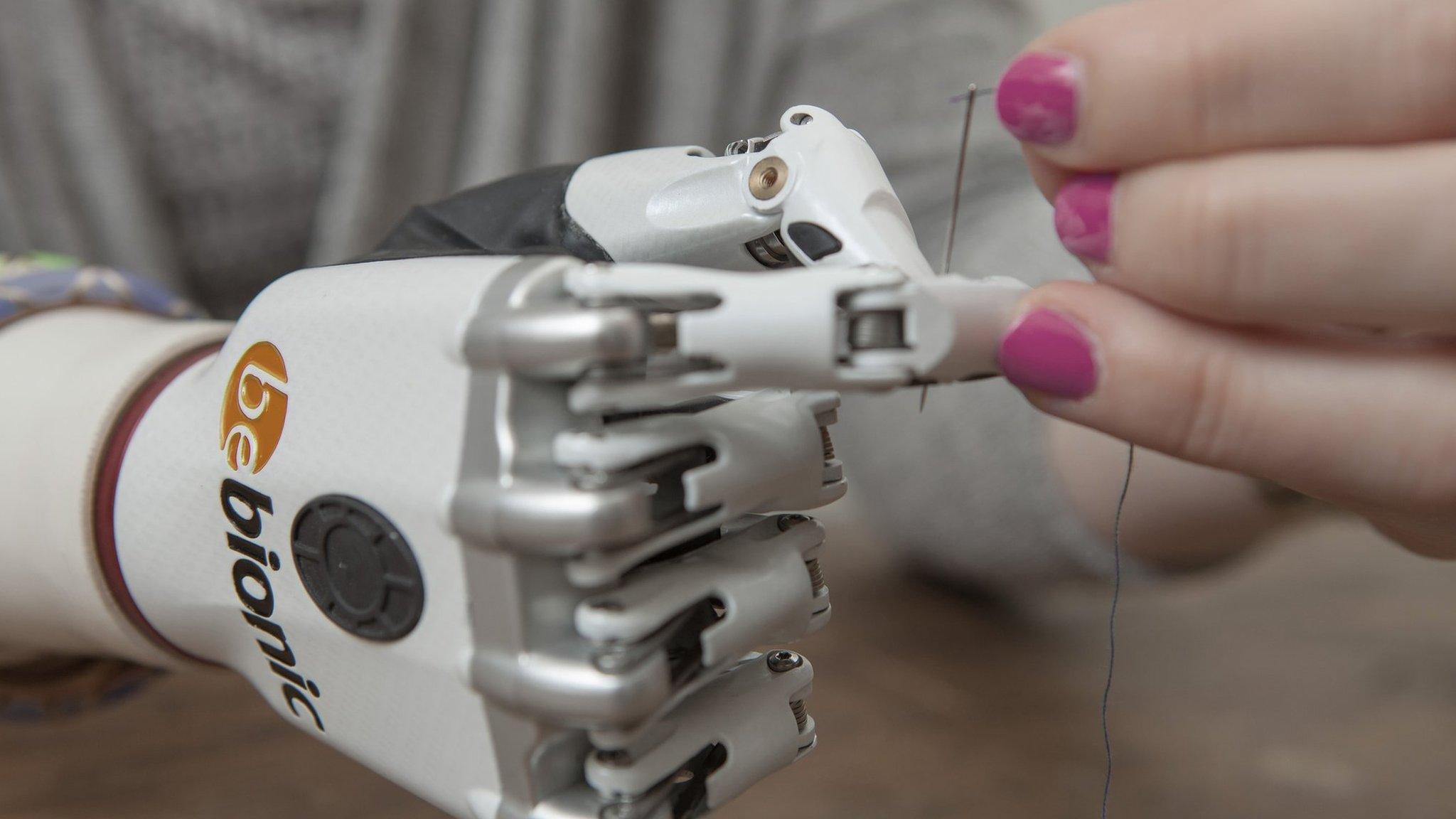

Nicky Ashwell's bionic hand has been created using F1 and military technology and is said to perfectly mimic the function of a real hand, with 14 possible positions. She says it has taken away "her awkward moments", and the movements are natural and easy to master.

Steeper, the company that made Ashwell's bionic hand, estimates that the whole arm costs about £30,000. It's undoubtedly the envy of many people without limbs, but few are likely to be fitted with one in the immediate future.

Stephen Davies's story is unfortunately more typical. When he went to his NHS prosthetic centre in 2008, he was looking for a more functional arm. He was struggling to mow the lawn and do the gardening so he needed a hand that could form a fist.

But when the hospital provided him with an arm that had a metal clamp, it was the last straw for Davies, and he left feeling annoyed and upset.

"It looked medieval, I couldn't believe it," says Davies from Swansea. "I had gone for so many years hiding my arm away in my pocket that I finally needed some help and they gave me this."

Stephen Davies was disappointed when he was given this arm in 2008

He decided to look at other options and found the charity e-NABLE who 3D-print hands for people around the world who are unable to afford bionic hands. While the designs are simple, they allow people to close the hand into a fist, or move fingers by flexing the muscles in their arm.

Davies was impressed, and raised funds to get the £2,000 needed to buy his own 3D printer. In two months he has printed his first hand and has been matched with Isabella, a young girl from Bristol, to make her a hand.

"There aren't many people doing this in the UK, so people are crying out for affordable options," Davies says. "Especially for children as they grow so quickly they need to update the arms regularly. Also kids absolutely love the 3D-printed ones because they can be so colourful. I've seen Iron Man ones, and Spiderman ones. It means they can go from being the child bullied in the playground, to being the coolest kid in school."

Stephen Davies wants to produce more 3d printed hands for children

But Patrick Chrimes is five, and has already decided he doesn't want a prosthetic arm. He recently told his mother, Katharine, that he likes his own arm just fine. He was born with a partial left hand, and has a thumb but no fingers.

Katharine would like to keep the options open, and is keen that he is fitted for an arm just in case, but with a quote of £30,000, it's a big risk if he decides he doesn't want to use it. "I just keep thinking what if he wants a job in the future that requires technical work? I'd hate to shut the door on that option completely," she says.

She is making sure that Patrick keeps the muscles in his arm strong in case he changes his mind and will need them to control a bionic hand, but for now, she just wants to do what makes him happy.

Bionic hands

"Ultimately it's up to him, but it's so difficult to try and say to a child that young: 'You may want this in the future so don't say no'," she says.

Having a child with a missing hand involves a lot of decision making, she says. When Patrick was first born, a surgeon offered to take one of his toes and make it into a finger. The operation involved attaching the bone and muscle from the toe underneath Patrick's "nubbin" - the piece of loose skin that is often naturally at the end of a stump, or purposefully left by a surgeon performing an arm amputation for protecting the bone. This would allow bone-room for the grafted toe to grow.

"It would give him a pincer at least," Katharine explains. "This can be really important for arm amputees as it allows them to pick up or hold objects."

Katharine says she and her husband toyed with the idea for a long time, but as it involved invasive surgery and rehabilitation, they decided against it.

Jo Dixon from the charity Reach which works with children with upper limb deficiency, says often even if children do get prosthetic arms they choose not to use them.

"Children are so versatile they often adapt ways to perform daily tasks such as cutting food and playing with toys with their stumps," she says. "Parents are always telling me how frustrating it is when their child just takes off their arm and leaves it on the ground. More often than not it's simply used as something to hit their sibling with."

For adults, who might be more willing to persist with wearing a prosthetic, and could treat an expensive design with more care, bionic arms are looking likely to be the future for arm amputees, says Ted Varley from Steeper, the company that made the BeBionic hand Ashwell uses.

"What they are able to do is just increasing," he says. "I think gradually prices will fall and they will become more mainstream which will probably mean that in the future they are more readily available on the NHS, or the cost-benefit will become more attainable."

Jo Dixon says people are using cosmetic arms less and less

He believes that 3D-printing is a red herring, and that often printed arms break as they are just not strong enough. "You could make a car out of Lego but it's never going to be as good as a metal one," he says.

Dixon says that when all is said and done, a prosthetic is just a prosthetic, and one of the main concerns for the people she encounters is people staring, or saying things.

"It's a very personal thing and varies from person to person," she says, "but working with children I have noticed it is often the parents who want to get their children prosthetic arms, in an attempt to normalise them in some way. While the bionic arms can look cool, it takes confidence from that individual to wear it all the time."

While this may be the case, she says there seems to be a move away from the more realistic looking arms, with a silicon cover made to look like skin, to arms that are more bionic looking.

She is excited about the future of prosthetic arms, but hopes that at some point the technology will translate down to children, and be available for everybody without financial constraints.

Follow @BBCOuch, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external, and listen to our monthly talk show