Viewpoint: Does this Spastics Society statue start the right conversations?

- Published

The statue aims to question the historical tradition of seeing disability and charity as pitiful

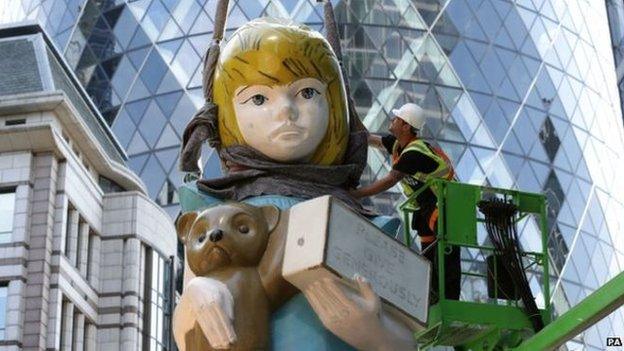

A giant sculpture of an old Spastics Society collection box has been erected in central London. It's aim is to trigger conversations about disability, but Kate Ansell doesn't think it helps.

It would have been rude of me not to visit this supersize disabled girl now standing tall outside the Gherkin in central London, because, like her, I used to be a girl in calipers.

It was created by artist Damien Hirst and is a 7m tall version of the well-known Spastics Society collection boxes which were commonplace in public in the UK until the 1980s. The girl is holding a teddy and a tin saying "Please Give Generously", but in Hirst's interpretation she's been broken into with a crowbar and loose change is scattered at her feet.

Apparently, the statue aims to question society's historical tradition of representing disability as pitiful.

Historical? Charming. I remember those collection boxes, and I'm not even forty.

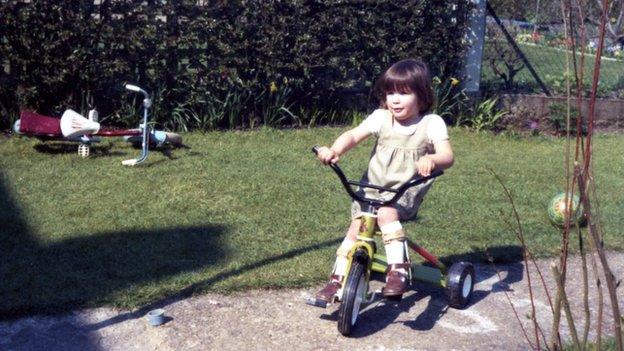

I have cerebral palsy and wore calipers growing up. As a child I was obsessed by images of people wearing calipers, and remember the Spastics Society collection tins vividly.

Kate wore calipers as a child

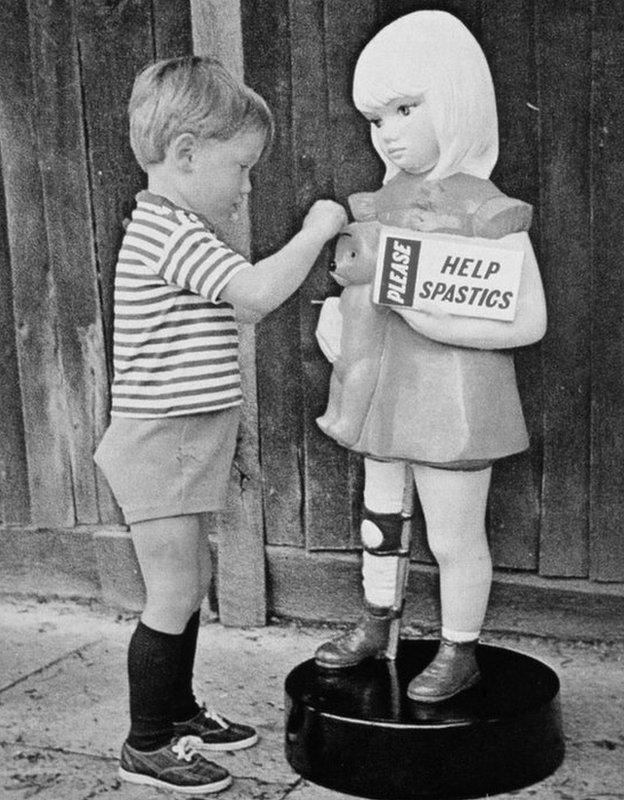

It was these collection boxes which introduced me to the concept of disability charity when I was small. I knew they represented girls and boys like me but didn't understand how or why. And as there were very few images of kids like me, I found a weird kind of affinity with the disabled child.

When I noticed people were putting money in the slot on her head, I asked why and was told it's because they wanted to help me. I genuinely thought I'd get all the takings and it blew my tiny mind. Someone - probably my mum - had to explain that I did not get it and there was a third party involved who decide how the money is spent. That's how I learnt that disability charities exist, and I didn't much like the idea.

A piece of me still wonders why those who want to help disabled people put money in a box rather than just help. But right now, I am wondering why people want to look at a statue and ponder an abstract situation, rather than engage with disabled people.

The Spastic Society collection tins were around until the 1980s

According to Hirst's own website, the multi-millionaire has long been a supporter of Scope, external, the disability charity that used to be the Spastics Society, and who owned those collection boxes. A comment on his site from the charity itself says the piece is "a symbol of changing attitudes to disability over the past 50 years."

You don't see those boxes around anymore, and the last time a disability fundraiser knocked on my door they were bearing colourful images of happy disabled children rather than pitiful ones. Charities have now mostly changed their tune.

These days disabled people have more of a voice than we've ever had. A group of disabled protesters invaded parliament the other day - but there's limited point in having a voice if it doesn't also carry the power to change things.

With the unveiling of this statue comes the intriguing realisation that disability is something people are expected to have "attitudes towards", like global warming or marigold wallpaper, but nobody seems to be encouraging anyone to pay attention to what disabled people say. Instead, it's suggested they gaze at a statue by a famous artist who isn't disabled, and think about people like us - all in the name of awareness raising.

The supersize girl with cerebral palsy has been displayed in London before, but that was ten years ago, and there is much excitement about this new unveiling, part of the 2015 open air Sculpture in the City exhibition. Since the statue is, essentially, a giant version of me as a child, of course I went to have a look.

A few people were wandering by, laughing at it, snapping photos with their smart phones and telling each other it was by Damien Hirst. I realise I'm taking this quite personally, but I did feel rather objectified. I don't think anyone appreciated that there was a connection between me and the statue - and I'm not sure that's a good thing.

For me, the girl is not a redundant artefact of times gone by, and neither are people's attitudes towards her - they're still here.

The statue is part of an exhibition over the summer

Scope, who are enthusiastic about the artwork, said they hope the sculpture will encourage conversations about disability amongst people in the capital city.

So I put this to the test and tried to catch the attention of fellow Londoners to see if they wanted to talk to me about disability while they looked at the piece of art. They didn't. But I'm not convinced we need a giant statue of a miserable disabled girl in the centre of the city to encourage conversations about disability. There are already loads of them going on.

In the last week alone, I've talked to other people about welfare cuts in the emergency budget, shoes, the vagaries of bus travel, the closure of the Independent Living Fund, and how complicated it is to do your own manicure when you have poor hand-eye co-ordination. Some of us do already talk about the everyday reality of being disabled on a regular basis. We don't need Damien Hirst, or anyone else, to encourage us to do that.

It would be nice, however, if people were encouraged to listen to us, rather than take selfies with a statue.

Next story: The business owner with Down's Syndrome

"I didn't want to work in ASDA. I wanted to run my own business" says 28-year-old Laura Green. The young entrepreneur from Runcorn, Cheshire, says that because she has Down's Syndrome people didn't think it was even worth talking to her about her future. READ MORE

Follow @BBCOuch, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external or email ouch@bbc.co.uk