How the dog pics you like could change who you vote for

- Published

Indie is a very friendly cocker spaniel

This is my friend's dog Indie, and surprisingly she has been influencing the kind of political messages I've been receiving in the run up to the UK General Election.

Indie is a very friendly cocker spaniel but she can occasionally take offence to complete strangers. This week a UK Independence Party canvasser knocked on my friend's door and she went crazy, barking, growling and generally making her displeasure known. My friend thought this was so funny that she posted an update on Facebook, and I clicked the Like button.

Then something strange started to happen. Perhaps because the post I liked had the word "UKIP" in it, I started to see more UKIP content appearing in my Facebook News Feed (the selection of updates and stories you see when you first log into Facebook).

Intrigued, I liked some of the UKIP content, and soon UKIP posters and videos about their manifesto launch started appearing in my feed. After more liking, the campaign literature of the other political parties I follow on Facebook seemed to be showing up less.

Inside the bubble

The term "filter bubble" was coined by the co-creator of the liberal-leaning social news website Upworthy, external, Eli Pariser. The term refers to what happens when a website algorithm selectively guesses what information a person would like to see based on information about that individual, for example, their location, past online behaviour and search history.

The effect occurs on all sorts of websites and social networks across the internet, but Facebook's News Feed is perhaps the best known example of this kind of algorithm. It's personalised, which is meant to make it a more interesting experience for you, the user.

But does this personalisation mean the political news you get becomes more partisan? Here's how to test for yourself: go to Facebook's UK General Elections topic page, external while logged in to the network. You'll see a variety of content scored for you, based on things such as what you've clicked on in the past and what your Facebook friends follow and like.

But if you open up a browser window in incognito mode (a function many, external browsers have) and navigate to the same Facebook topic page, you'll see a different, unfiltered stream of content on the same topic.

Susan Halford, the co-director of the Web Science Institute at the University of Southampton, told BBC Trending that this phenomenon was not unique to Facebook and extends, in different ways, across the internet. "Every time we use a service like Facebook or Twitter, or Google, we leave a digital trace," she said.

"These services will take this data and infer things about our preferences and will decide what kinds of information we want to see. The web is not simply open, it is being filtered through these different services so we only see content which is driven by the algorithms that companies have devised to push information out to us."

Gilad Lotan, the chief data scientist at digital start-up Betaworks, external, has studied filter bubble effect across various social media networks during the Scottish Referendum and during the conflict between Israel and Gaza. He told BBC Trending that the effect causes a serious problem for voters.

"The consequences of these growing filter bubbles are pretty grave especially at a time when the majority of youth get their news from social networks," he said. "Social networks were supposed to be the great equalisers but although we are only a few hops away on Facebook from anyone else, on a network of a billion people, we're [still] seeing increasing polarisation politically."

"Because in social networks a lot of content comes from your friends, you need just need one friend who turns politically right or left during the elections, then you start receiving all this content".

The filter bubble also presents a potential problem for politicians. How can they get into the social media feeds of undecided voters, the ones who haven't liked any of their stuff already? One solution: to pay for advertising, to increase the number of times that users are exposed to a political party's content.

All the UK parties are doing this on Facebook and other platforms, and there has been lots of discussion in the UK press about the fact that the Conservative Party has focused its resources on advertising on Facebook. It seems to be paying off: David Cameron's personal page has 518,000 likes. Nigel Farage has 180,000, Nicola Sturgeon 154,000, Ed Miliband 90,000, Nick Clegg 85,000, Natalie Bennett 17,000 and Leanne Wood 13,000.

Elizabeth Linder is Facebook's Government and Politics Specialist - it's her job to advise politicians on how best to engage with Facebook's users. She told BBC Trending that her team provides support to all candidates regardless of how much money they had spent on advertising on the platform.

She also vigorously defends the News Feed: for her the platform is not political because it sometimes reflects your own preferences back to you. "I think the same could be said for a company that's printing brochures," she said. "Is the company that's printing a political brochure inherently an instrument of politicking? Well no, its the person that's actually choosing to print those brochures that's making that decision to use the space."

Political elections are the third most popular subject on Facebook worldwide, so the platform has a vested interested in encouraging politicians to join the online discussion.

'Unfiltered' Twitter

So that's Facebook, but what about Twitter - it's seen as the social network most associated with political news. A Twitter feed is not "filtered" by an algorithm - despite reported plans, external by the firm to launch a filtering algorithm.

But there is a more limited filter bubble effect. When a user joins Twitter, the platform suggests a number of accounts they should follow. Every time a user follows a new account, the website learns what kind of accounts the user is interested in. Over time, Twitter starts to suggest similar accounts to the one the user's political preferences. So to a degree Twitter mirrors real life, in that we chose to pay attention to people whose ideas we agree with.

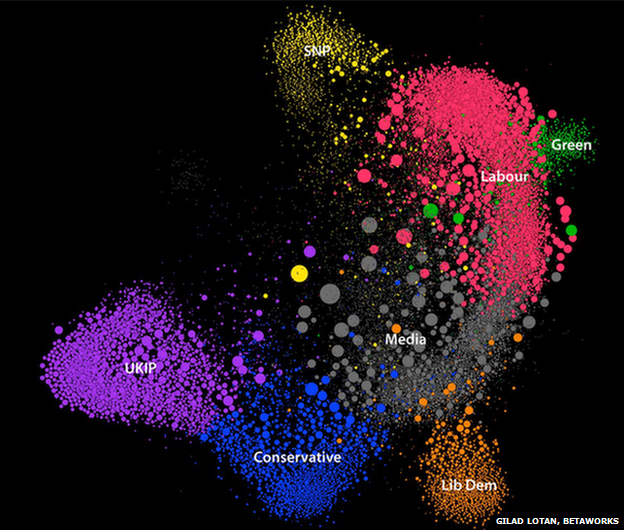

It is possible to map this behaviour. The below data visualisation made by Gilad Lotan shows the Twitter accounts which were active in the second week of the official General Election campaign. "I took a week's worth of data from the hashtag #GE2015, and looked at who was following who," he says. "Using the personal description given by each user I then coloured each user into the political party they were affiliated with."

What Gilad's data shows is that all the political parties supporters are generally distinct, all sending out tweets to a relatively narrow audience of supporters, who do not follow many accounts from other political parties. This affects how the users perceive news events in the general election. However that's not to say there are no relationships between political preferences - and you can see some of them in the pattern above.

It's impossible to know for sure whether this spread is due to the filter bubble effect, or the actual political preferences of each user. The "media" cluster, which refers to news media accounts, is roughly in the centre. It sits slightly closer to the Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat users because the Twitter accounts in Gilad's data focussed more of their attention on these three parties, at the expense of following users who supported the SNP, the Greens and UKIP.

So what does the filter bubble effect mean for voters in the UK election? Facebook, Twitter and other social media algorithms try to mirror our real life relationships. So in some sense it's not surprising that as humans and citizens, like Indie the dog, are partisan in our views (in fact, she's very partial in deciding who she likes and who gets the cold shoulder).

But before heading to the ballot box on May 7th, it's probably wise to do your research from a wide variety of sources on who best deserves your support.

Blog byHannah Henderson, external

Hear more on this story on Campaign Sidebar, on BBC Radio 4, Saturday 18th April at 11:00

Next story: Why other Africans are calling South Africa 'xenophobic'?

If you like BBC Trending's reporting, please do vote for us, external - we've been nominated for a Webby Award.