Why is a feminist posting rape videos online?

- Published

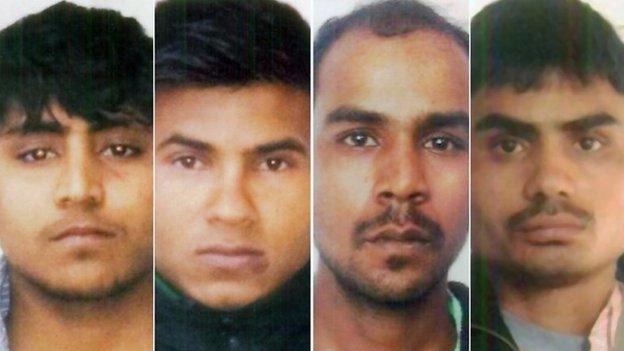

Four men convicted of a notorious gang rape and murder on a Delhi bus in 2012 have appealed against their death sentences

Women fighting India's "rape culture" have used the internet in highly creative ways - but is posting rape videos onto YouTube a step too far?

"I watched the video and to my utter shock, it was an untampered video of rape." This is how Sunitha Krishnan, founder of anti-sex trafficking charity Prajwala, describes watching the first WhatsApp rape video she discovered back in February.

"It was absolutely nauseating and I just couldn't continue. The whole thing was a young girl who was being gang raped by five people."

"What was shocking was that these people were aware of a camera, they were getting it all recorded. They were laughing and there was this huge sense of gloating."

The video was shown to her by a man who attended one of her public talks, and whose own cousin had shared it.

Krishnan realised it was one of many such videos doing the rounds in a shocking and perverted subculture which seems to have many adherents in India.

The "scene" is driven by rapists themselves who share the videos - and, shockingly, don't bother to hide their own faces - using messaging apps such as WhatsApp.

(We are not showing any shots from the video or linking to it and recommend you do not search out these videos - they are both violent and disturbing.)

Krishnan, who is herself a survivor of a gang rape at age 15, was also deeply shocked. She is a respected feminist, external, and is one of the many Indian women who have campaigned creatively using the internet to challenge India's attitudes towards violence against women.

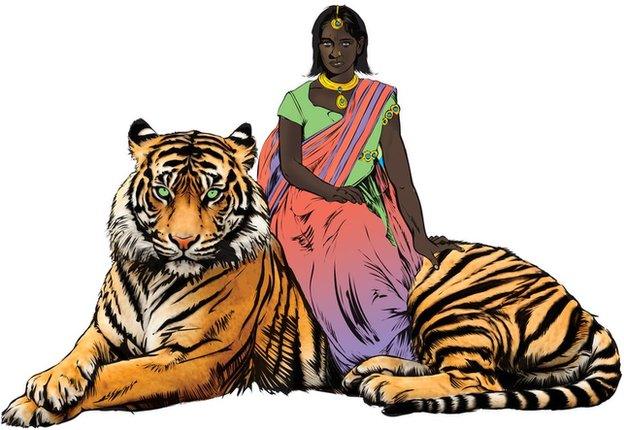

Online campaigns such as "I never ask for it," or the comic super hero Priya, a rape survivor, have galvanised the online conversation, and been widely discussed, especially since the brutal gang rape and murder of Jyoti Singh on a Delhi bus in 2012.

A new comic book with a female rape survivor as its "super hero" was launched in 2014 to focus attention on the problem of sexual violence in India.

But what Krishnan did with the video took Indian online feminism into new - and controversial - territory.

She made the decision to edit it, to blob out the faces of the victims, and upload it to YouTube.

"I decided that enough is enough," she told BBC Trending's Anne Marie Tomchak, for a radio report you can listen to here.

"The very next day... I captured the pictures of these young men from these videos and exposed it to the world."

In the weeks that have followed, Krishnan has posted more such videos on social media - and been sent even more by those who support her aims.

It's provocative and certainly gained attention. But is it the right way to combat what some have called India's "rape culture"?

One concern is that showing the faces of men who appear to be committing a crime, before they have been subject to criminal procedures, could encourage vigilante violence.

BBC Trending asked Krishnan if she was in effect taking the law into her own hands, she defended the practice.

"The offender is using this medium to shame somebody and to show their impunity," she said.

"Why should I be so sensitive to their needs?"

After posting videos online, Krishnan says she does hand them over to India's Central Bureau of Investigation. To date, she says, three people have been arrested.

Sunitha Krishnan, founder of the Hyderabad NGO Prajwala

Many in India have railed against Krishnan for undermining the rule of law.

For feminists, there is also the issue of consent - because while the victims are blobbed and their identities hidden, they don't seem to have been consulted before the videos are re-posted.

"I do not question her intention," says Jasmeen Patheja, from Blank Noise, an online feminist group, external. "But the approach... is something that I'm not in sync with."

"It's the survivor themselves that should own the narrative," she says.

The very existence of these videos shows there is a long way to go in tackling those aspects of Indian culture that embolden the perpetrators of sexual violence.

Online campaigning, and the receptiveness of the media to talk about the issue, have certainly produced big changes since 2012.

"There is a big shift," says Patheja. She says it's happened on social media networks, on TV news channels, in films and even in adverts - with one recently showing a kiss between a loving lesbian couple, external.

Campaigns like "Shame The Rapist" are certainly much more radical, but, says Patheja, "they are still "part of that shift".

Additional reporting by Anne-Marie Tomchak

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.