What's the point of sexual consent classes?

- Published

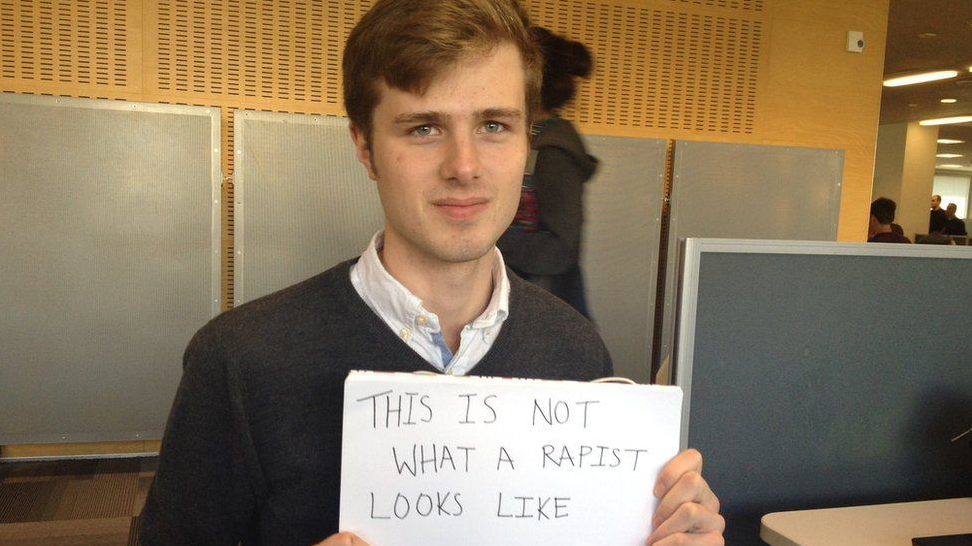

George Lawlor's post detailing why he was offended by being invited to a sexual consent class kicked off a debate online

Do young people really need a class to learn about sexual consent?

George Lawlor doesn't think so. He's a 19-year-old second year student studying politics and sociology at the University of Warwick.

When he received a Facebook invitation to a consent class, he was so angry he penned an article for a campus news site, external calling it "loathsome" and "the biggest insult I've received in a good few years".

"For someone to assume you don't know how to interact with compassion for fellow people - that's a bit of an offensive thing to say and to accuse somebody of," Lawlor told BBC Trending.

"It's just that I feel if you need to be taught what consent is and what consent isn't, then you don't have respect for other human beings."

But how clear-cut is consent, particularly in the kinds of social situations involving drink and drugs in which university students often find themselves?

Under British law, specifically the Sexual Offences Act 2003, a person has to have the "freedom and capacity" to choose to have sex.

And advice from the UK's Crown Prosecution Service notes that capacity is particularly relevant when alcohol is involved - a person for instance can't consent if they're too drunk or high, although that's a subjective test which doesn't depend, for instance, on blood alcohol levels.

The National Union of Students (NUS), the UK's main body which represents people studying at universities, says that there's a lack of information about consent which is part of the reason why one in seven women say they experience a serious physical or sexual assault during their university career.

NUS Women's Officer Susuana Amoah says consent courses, external cover legal aspects of consent as well as social situations and general sexuality education.

"We start out with basic conversations about what people think is and isn't consent and their examples.

"We believe that people at first don't have a clear-cut idea about what consent means, so we want to explore the various definitions," she says.

Amoah admits there's no hard evidence that the classes, which are more common in the US but spreading rapidly in the UK, reduce the incidence of sexual assault - but she chalks this up to patchy reporting of these incidents on campus.

Susuana Amoah has been promoting the classes on behalf of the NUS

Meanwhile, Lawlor's post provoked a huge reaction on social media.

"What kind of deranged feminist assumes that every male student is a rapist and forces them to take a consent class?" tweeted one critic of the lessons.

Another said: "People do understand consent, sadly some disobey the wishes of another party. A class won't stop this by itself."

The debate did not break down strictly on gender lines, with some men coming out in favour of the courses and some women being against them.

"These consent lessons have good intentions," tweeted journalist Caroline Criado-Perez. "But I think they misread the problem. Rapists aren't ignorant. They just don't care."

Rebecca Reid, a feminist commentator and Daily Telegraph columnist, called the courses "a waste of time" - but her reasons were very different from Lawlor's.

"I think by the time someone is 18 or 19 years old they've already got a fixed understanding of what's acceptable and what's not," she said.

"I think consent classes would be a very important and a very useful thing - if you started them from childhood."

But instead of eliminating them completely, Reid says she'd like consent education spread more widely across the university curriculum.

"If a university is going to work against sexual assault then in the first week when they talk to you about being careful where you put your money and looking after yourself, not getting meningitis, not using the neighbour's bins - that's the moment to take 15 minutes with all the young freshers (first-year students) to lay down the law and to make a clear point about what is and isn't acceptable."

Lawlor sticks to his general objections, but since his post touched off the debate he has had one change of heart - he plans to attend one of the classes.

"I think it's only right and fair that if I criticise something I have to experience it," he says. "But I don't feel as if I need it, I feel that I have to go because I've written about it."

George Lawlor has had a (partial) change of heart

Additional reporting by Anisa Subedar

Next story: Can men really have it all?

One anonymous Twitter user takes the often inane nuggets of advice dished out to working mothers, and flips genders. The "Man Who Has it All, external" tweets parody tips for working fathers.

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.