The latest codeword used to beat China's internet censors

- Published

The character "Zhao" is being used online to criticise the powerful

It's one of the most common surnames in China - so why do Chinese internet censors suddenly have a problem with the word "Zhao"?

When it comes to criticising powerful people online in China, there's a long tradition of being indirect. Around a year ago, hundreds of social media users began using the sarcastic phrase "ni guo," meaning "your country", to express their distance from the views of the Chinese government. It was a clever play on words: "my country" had become a common nationalist phrase used by state media organs.

Because the words "your" and "country" are so commonly used, it was difficult for government censors to filter social media posts containing the phrase, and it got popular.

At the end of 2015 and now in early 2016, a new word - the surname "Zhao" - has started being used for the same reason, replacing "your country" as one of the most popular terms of criticism towards those who are rich and powerful.

How people are using "Zhao" in China

A "Zhao family member" is someone with a vested interest, someone who holds actual power.

"Zhao in spirit" is someone who thinks they can benefit by association with those in power.

"Zhao in spirit" in particular pokes fun at those who get excited about the military, "who gaze at the flag with tears in their eyes".

Source: Discussion on zhihu.com, external

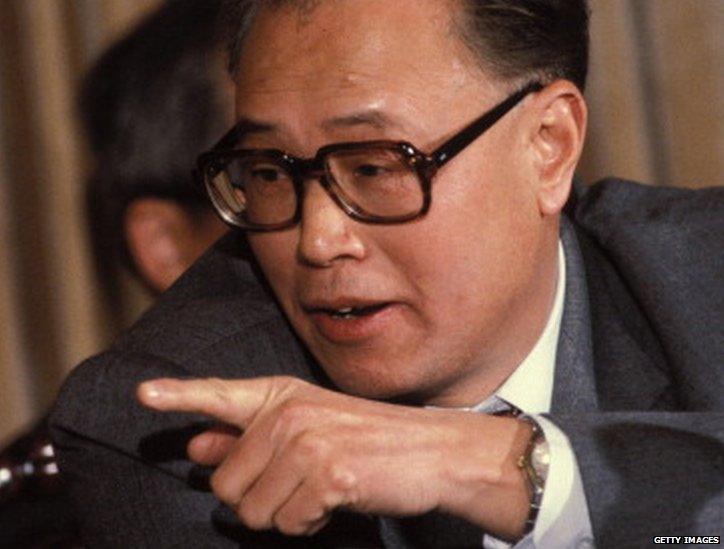

But what does it actually mean? "Zhao" is actually one of the most common surnames in China. It was the family name of the late Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang who died, external in 2005.

Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang

On the online forum Zhihu, people discussed its origins, external as a political term, and most seemed to agree that its adoption on social media is a reference to a character in early twentieth century writer Lu Xun's acclaimed novel "The True Story of Ah Q".

In the book, Zhao is a landlord from a prestigious clan who beats Ah Q, a peasant who bullies those less fortunate than him, in a fight.

Because Zhao is such a common name with ancient origins its new usage was not immediately picked up by Chinese state censors.

Vincent Ni of the BBC Chinese Service says the way social media users are using "Zhao" is in line with a Chinese linguistic tradition which pre-dates the internet. "Chinese people have long used what are known as 'oblique accusations' which enable them to express their opinion when it would not be possible to make a direct criticism of those in authority." he says.

Statue of author Lu Xun in Shanghai

"By using certain apparently innocuous phrases - that are understood by some people to have a different meaning - it is possible to make an indirect criticism. Eventually the censors realise the double meaning by the phrase and take action. So for this reason we are likely to see more phrases emerge to perform this function."

Since the end of December and following a number, external of articles, external pointing to its growing popularity, the censors have started to cotton on to its increased usage. Free Weibo, a website that captures censored Weibo posts, shows that "family Zhao" and "people of the family Zhao" have been popular censored terms in the last day or so.

Follow BBC Trending on Facebook

Join the conversation on this and other stories here, external.

On 3 January, a user on the Sina Weibo network named Lelige posted an image of what appeared to be guidelines from a government official on acceptable terminology on Sina Weibo. "Please can all journalists pay attention, and ensure that there are no messages on Weibo, WeChat etc. that contain 'excellent Zhao', 'honoured Zhao', 'family Zhao', 'Zhao kingdom'," it said.

It's impossible to verify his post, but it seems to now have been one of many censored from the popular Sina Weibo site.

Blog by Kerry Allen, BBC Monitoring

Next story: Did this politician's watch cost more than his car?

A public display of patriotism by a Russian politician buying a Lada car backfired - as many focused on what appeared to be his luxury Swiss watch instead. READ MORE

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.

- Published30 November 2015

- Published11 September 2015