Trolls and triumph: a digital battle in the Philippines

- Published

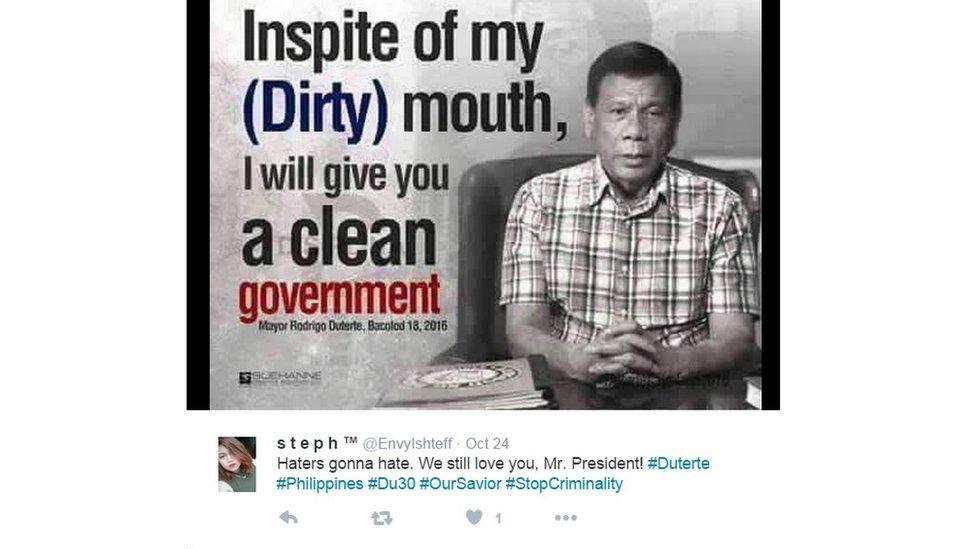

This year, an authoritarian, anti-establishment firebrand, famed for his controversial statements and uncompromising stance on law and order, won a presidential election with the help of a divisive, innovative social media campaign.

No, not Donald Trump, but President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines.

During his campaign Duterte, nicknamed "The Punisher", promised harsh punishment for those suspected of using and selling illegal drugs.

Dealers, he said, would be "fed to the fish in Manila Bay." (And that was not his only threat - here's a few of his most notable quotes). Many attributed his popularity to his straight talk, but something else also helped Duterte secure the presidency - social media.

Maria Ressa, founder of the Filipino social news site Rappler, has investigated the machine built by the Duterte campaign.

"Duterte was the only candidate who took it seriously," she says of the power of social networking. "They (his campaign) claimed it was because they had no money and social media is essentially free."

That idea is backed up by the man who steered the president's strategy, former advertising executive Nic Gabunada.

"When we realised we didn't have money for TV, radio, print, billboards etc, we made the decision to tap up the social media groups," Gabunada says, "How did we organise them? We reached out to them, we assigned co-ordinators."

Those co-ordinators were in charge of particular geographic regions of the country and one group was devoted to Filipino workers overseas. Each group received targeted, bespoke messages, relevant to their own immediate experience.

"During the campaign we had a 'message for the week'. It was really up to each group to amplify that message to their own circles and to craft how that message is best framed in their own networks," Gabunada says.

A mobile phone game showing President Duterte combating crime in the streets has been downloaded thousands of times.

With the help of those overseas workers, Gabunada was able to make the Duterte machine work 24 hours a day.

"Late at night the people from abroad, the (workers) in a different time zone took over, people from Europe, people from down under, or the Middle East," he says,

The campaign also rallied the help of high profile digital influencers, and using the hashtag #Du30 (a hashtag that rhymes with the president's name).

The influencers were chosen for their connections to messages central to the Duterte campaign.

"Some of them have very real experience of how crime has affected or destroyed their lives," says Gabunada, "like Mocha, whose father was murdered."

The "Mocha" he's talking about is Mocha Uson, one of the biggest and most controversial faces in the Duterte volunteer network.

She's a Filipino singer with more than four million Facebook followers. She released songs supporting the president during the campaign and her group played at Duterte rallies.

Pop star Mocha Uson became one of Duterte's most famous - and controversial - volunteers

"I uploaded the videos of his rallies," she tells BBC Trending. "And it is only through social media that Filipinos saw how many people actually supported him, because they didn't show that on the mainstream media."

Uson put up 20 to 30 political posts a day. One photo she shared claimed to be of a Filipina who was raped and murdered - but the picture was actually taken in Brazil. She later took it down.

More reporting on the Philippines from the BBC Trending team

Listen to Trolls, 'the Devil', and Death on the BBC World Service

Watch Manila's brutal nightshift: the photographer on the front line of Duterte's war on drugs

Read No country for poor men: the human cost of the anti-drugs campaign

Mocha tells BBC Trending that she's also willing to hold the government to account, but it's not totally clear Nic Gabunada sees her in the same way.

"Filipinos are like that actually, as long they are able to get your message, they will work for you," he says, "I have a term for that. Arouse, organise, mobilise. That's the secret."

Rappler founder Maria Ressa agrees, but says that one intriguing aspect of the Duterte campaign is that it didn't end with his election victory.

"Most of the time you'd think when you win, you retire your campaign machinery, but not in this case. The campaign helped change values and perceptions in our society and we're watching it unfold in the first months of his presidency."

Rappler investigated online networks of Duterte supporters and discovered that they seem to include fake news, fake accounts, bots and trolls, which Ressa thinks are being used to silence dissent.

Follow BBC Trending on Facebook

Join the conversation on this and other stories here, external.

"What we're seeing on social media again is manufactured reality... They also create a very real chilling effect against normal people, against journalists (who) are the first targets," she says, "and they attack in very personal ways with death threats and rape threats.

"The weaponisation of hatred I think is what you're seeing."

Indeed, journalists in the Philippines critical of the Duterte campaign were subject to online intimidation.

"Even at press conferences, which are televised live... journalists get immediate responses if they ask any question that challenges him," says Ressa, "and the responses are 'you should die', 'you should get raped'."

Ressa says that the messages often appear to originate from pro-Duterte accounts and are then amplified through the Duterte support network in order to create a powerful wave of dissent against those that challenge the president.

But the notion that fake or troll accounts are driving the president's social media machine is denied by Mocha Uson. She points to her huge numbers of fans as proof that Duterte's support is real.

"On my Facebook I have 4.4 million followers and the engagement is as high as 3.6 or 3.7 million. Maybe (critics) are the ones who have these trolls or bots or fake accounts."

Duterte drawings, murals and memes were shared widely online

Nic Gabunada points out that dirty tricks were not exclusive to some of the president's supporters.

"It happened not just from Duterte but from other camps," he says. "You cannot expect to control all people in the social media sphere, people have been given a weapon and a medium where they can express themselves, so you should understand this is a whole volunteer movement, you cannot control everybody."

Blog by Kate Lamble and Megha Mohan

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, and find us on Facebook. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.

Next story: The dad who asked for donations - even though he's well-off

A row has erupted on social media in China over a father who raised money for his sick child without disclosing what some people argued were substantial assets of his own.READ MORE

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.