Grenfell 'miracle baby': Why people invent fake victims of attacks and disasters

- Published

Malicious pranksters have made up fake stories about Grenfell Tower and terror attacks in London and Manchester. Why?

Stories of fake victims routinely crop up online in the wake of attacks and disasters, but they're spreading further and faster because of social media. The motivations of the hoaxers vary from financial gain to pure pranking to bizarre political point-scoring.

It would have been a miracle - if the story was true.

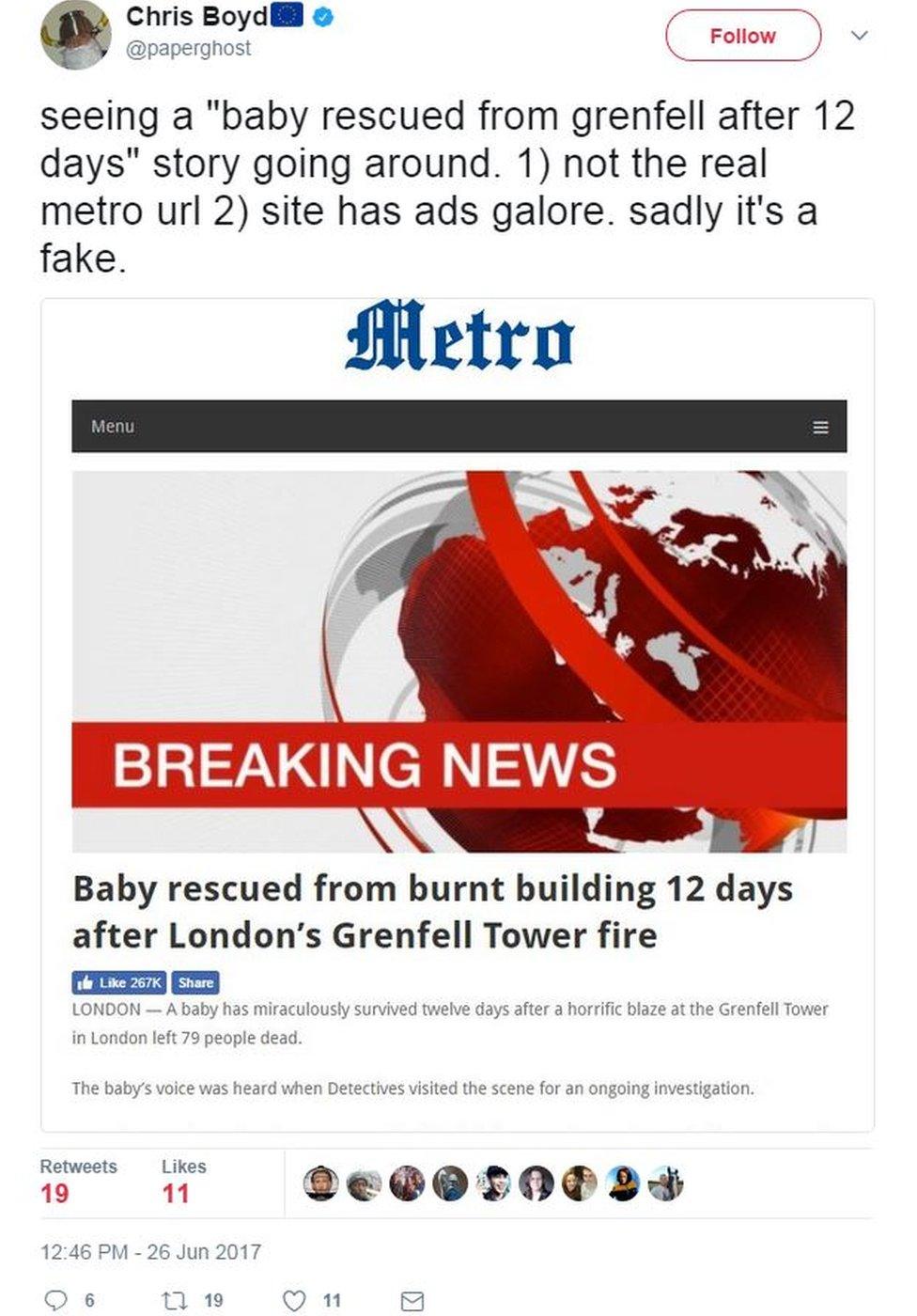

Over the weekend, rumours began to circulate on Twitter that a baby had been rescued from Grenfell Tower, nearly two weeks after the inferno that killed at least 80 people.

The story was a hoax; the baby was just the latest made-up person affected by a disaster or terror attack.

It started on a clickbait-heavy fake news site which uses the name of a real media outlet ("Metro"). The story also swiped the BBC's breaking news graphic to create an alert that appears real enough - if you don't look too closely.

But "the miracle baby", debunked by many mainstream news outlets, external, is actually somewhat unusual in the recent annals of fake victim invention.

BBC Trending noticed a spate of fake victim pictures on Twitter in the wake of this year's terror attacks in Manchester and London - some were posted online within minutes of the attack. The fakes take the form of a tweet, urging members of the public to look out for someone, with an attached picture usually taken from some other website or social media account.

As posts are often deleted by the original posters or taken down by moderators, it's hard to quantify exactly how many fakes emerged, but some get retweeted hundreds or thousands of times.

"The primary reason that people do this kind of thing is that the behaviours work," says Whitney Phillips, author of a study on trolling, This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things.

"Journalists immediately descend on these kind of stories often to decry the stories, but what ends up happening is that in these same stories which are attacking these trolling behaviours is the journalists are reposting many of these same photos.

"People do it because they want a reaction and they know they're going to get it," Phillips told BBC Trending radio.

Hear more

Stream or download on BBC Trending radio

In the wake of the Manchester suicide bomb attack, photos of the missing and dead began circulating online, but one picture that ended up in some news reports was a fake - it was an image taken from the Instagram account of a 13-year-old girl from Melbourne, Australia.

"It was on the news here in Australia, it was all over the place," says the girl's mother, Rachel Devine.

Rachel Devine says the photo had been posted by her daughter Gemma about a year ago,

"Gemma's first reaction was 'Why are they worried about me, can't we be worried about the actual victims?'

"I don't understand what that person behind that Twitter account had to gain because it didn't do any damage to us, it didn't affect Gemma it only took away the spotlight from the people who actually needed to be found, or to be helped," Rachel says.

Tamara de Anda's photo is posted online in the wake of attacks, along with false messages claiming that she is among the victims

In some cases, however, the motivations are clearer. Tamara De Anda is a Mexican journalist who was in the news after a taxi driver was fined for catcalling her in the street. Since then she's been on the receiving end of death and rape threats, and in the most recent form of online bullying, her picture is posted online in the wake of attacks and disasters along with claims that she is a "victim".

"Every time there is an attack I am sure there will be a few pictures of me around," she says. "The last time it happened I knew that a picture was being shared before I knew about the attack."

"I think there's a few people controlling a lot of accounts," she says. "Their attacks are coordinated and sometimes they make sense and you might get a feeling about how they're connected to the political situation in Mexico. Sometimes it's just hate."

Visit BBC Trending on Facebook, external

BBC Trending contacted a number of the people who were spreading the false rumours. Several admitted they were in it for the laughs. One was a self-described "fascist" who said they were a teenager living in the United States. He mocked people who retweeted his hoax, in which he created a fake London Bridge victim.

"That tweet was a public service … I made these 'people' [who retweeted the picture] feel good about themselves didn't I? … If anything I should be lauded," he said via Twitter.

Whitney Phillips, the expert in trolling, says that despite the varying motives, the pranksters tend to have a pattern when picking out their fake "victims".

"Around the globe, far-right actors have made great efforts to engage in media manipulation... and one of the ways that's done is to go after the most vulnerable populations or historically underrepresented populations, populations that they see as occupying a 'politically correct' or 'social justice warrior' ambit," she says.

"Overall the effort is to manipulate and to harm those who are vulnerable or perceived to be vulnerable," she says. "And so that's the underlying thread even if the actual individuals participating are different and have different motivations."

Blog by Mike Wendling, external

With reporting by Kayleen Devlin

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.