Why ordinary Iranians are turning to internet backdoors to beat censorship

- Published

Numerous apps that are often required by Iranian social media users who want to continue using blocked social media services such as Telegram

Social media in Iran is carefully controlled, but its usefulness - including in organising protests - leads many ordinary Iranians to see out ways around the censors.

Most young people in Iran already knew how to bypass internet blocks by using proxies and virtual private networks (VPNs). As a result of recent protests in the country, restrictions became tighter - some social networks were temporarily banned.

The move forced many less savvy and the older internet users to install VPNs on their mobile phones.

VPNs route internet traffic through different computers and networks and can in effect trick the censors by making a user "appear" to be outside Iran. But of course the authorities are aware of such tricks, and it's a game of cat and mouse, with censors hunting down VPNs and ordinary Iranians finding new ones.

Internet censorship is very sophisticated in Iran and mapping how people get around it is even more complicated. So here are some key questions - and answers - about the way Iranians use social media and the internet.

1. What social media channels are big in Iran?

Telegram and Instagram, mainly because they are not blocked most of the time. (Although Telegram is "temporarily" restricted now).

Telegram is an instant messaging service - if you're not familiar, it's in a similar category as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. Telegram users can communicate one to one, or subscribe to channels which can broadcast messages.

Instagram, of course, is the Facebook-owned photo-sharing network.

2. What about Facebook and Twitter?

Facebook and Twitter are officially blocked but many users are active on Twitter via proxies. The BBC Persian Twitter account, external, for instance, has one million followers. Restrictions have changed users' behaviour. Broadly speaking, Iranians use Telegram like Twitter and Instagram like Facebook.

3. Any others?

WhatsApp was never popular in Iran, but the recent ban on Telegram has pushed many users to it. There's also a host of domestic apps, including one developed by the state broadcaster, called Soroush. The government has also recently removed the ban on the Chinese instant messaging app WeChat. But many users don't trust these apps to keep their messages private and secure.

You might also be interested in:

4. Why is Telegram so popular?

Iranians turned to Telegram after another popular instant messaging app, Viber, was blocked. Telegram was marketed as a "secure" app, which made it hugely popular with Iranians who were mindful of surveillance. About 40 million Iranians use Telegram - that's half the entire population.

5. What is Telegram used for?

Personal messaging, entertainment, business and even crime.

Iranians use private groups to keep in touch with family and friends inside and outside Iran. But they also use its public channels for entertainment, business, education, and news. There are hundreds of thousands of channels. According to an official body, public channels providing various services made more than $20 million in 2017 (before the ban). Almost 40% of Iran's international internet bandwidth is taken by Telegram traffic, and 66% of online crimes are reportedly related to this app.

This image of a female protestor was one of the images widely shared on social media during recent protests

6. How exactly are protests organized through social media in Iran?

Telegram is believed to have been the main platform people used to obtain and share information about the recent protests. It is said that the first call to attend the protests in the city of Mashhad was posted widely on local public channels of Telegram. During the widespread protests, the location and time of gatherings made the rounds on Telegram channels and groups.

7. Why do Telegram and other social media platforms keep getting blocked?

Internet regulation in Iran is complicated and involves a wide range of stakeholders from opposing sides of the political spectrum. Government, judiciary, religious leaders, political parties and businesses, all might put pressure to block or unblock a social media platform.

There is a committee within the judiciary that defines and determines criminal content on the web - it's called the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, and it's chaired by the President and sets its own policies.

The clergy and the more conservative segments of the Iranian political establishment tend to push for more restrictions. The Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is known to watch internet developments closely. Despite the enthusiasm for censorship, Mr Khamenei has verified profiles on most platforms, including Twitter.

On the other hand, there is money to be made online, and private sector businesses tend to have a stake in opening up the internet. Some of the big businesses owned by or connected to the Revolutionary Guards (IGRC) and influential state figures also lobbying for their interests.

Because of the multiple and overlapping power structures within the Iranian government, there is no simple answer to questions like "Why does Iran block Facebook but not Instagram?" or "Why is WeChat suddenly available after being banned for four years?"

8. Why aren't the Iranian authorities banning platforms indefinitely?

Again, it's the competing political and financial interests inside the government which help explain the story.

President Hassan Rouhani, in his re-election campaign last year, pledged to improve freedom of access to social media. And only one week before the current protests began, Mr Rouhani insisted that his communications minister would "not press the button that blocks social media" - a pledge he went back on by temporarily banning Telegram and Instagram. But it would be enormously damaging Mr Rouhani to allow an indefinite social media ban.

There are around 41 million internet users in Iran and almost 50 million own a smartphone. With the expansion of mobile data in the country, a more comprehensive social media ban would cause huge discontent - and most likely drive even more Iranians to use VPNs.

In addition, many businesses are now shaped around internet access, including some hugely profitable ones owned by individuals with close ties to the establishment.

Conservatives also have political motivations to keep social media available. Online conservatives called "Arzeshi" now undertake well-funded social media campaigns to voice their full-throated support for the supreme leader - including on banned platforms such as Twitter.

And like in many countries around the world, politicians also use social media to directly reach their supporters. With only limited access to state-controlled television, President Rouhani live-streamed his election campaign on Instagram last year. Digital media is the only way that the more moderate political figures, including MPs, the president and his cabinet members, could directly talk to their electorate.

9. Are social media companies complying with the Iranian authorities - to what extent? How does the relationship between tech companies and the government work?

The simple answer is, it's complicated.

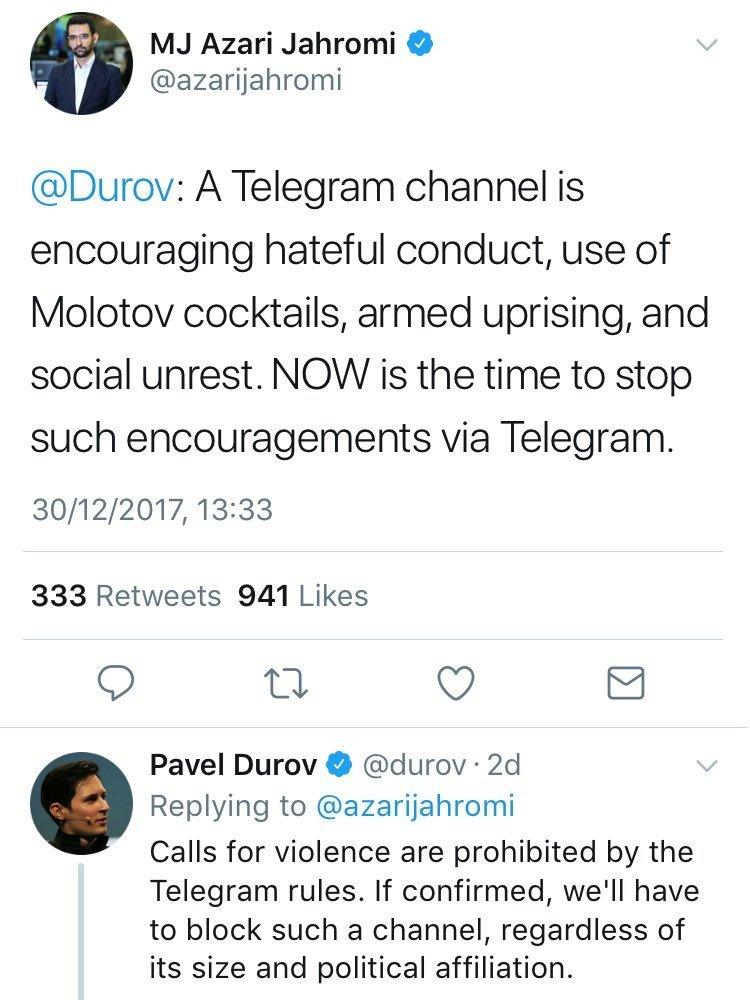

During the recent protests, information technology minister MJ Azari Jahromi tweeted to Pavel Durov, the chief executive officer of Telegram, asking the company to stop a channel "encouraging hateful conduct, use of Molotov cocktails, armed uprising and social unrest".

Durov replied by quoting Telegram's policies, and within hours, the channel (@amadnews) was suspended. Many criticized Telegram for complying with the Iranian request.

The main issue that the Iranian government, like many other governments, have with tech companies is that they would like to access information about citizens and dissidents for purposes of political control. However, Iranian authorities are also keen to have their cooperation on issues like pornography, and what they call "Islamic morals".

The Telegram ban, it seems, has not been as effective as the authorities wished. According to the numbers crunched by Telegraphy, external, the volume of content published on more than 600,000 Farsi public channels showed no marked fall. In fact, it stepped up again a few days after the ban. It's clear that many more Iranians are turning to VPNs, and getting online by circumventing the censors.

More from Trending: KFC parodies Trump with McDonald's jibe

The rivalry between fast food giants has taken on a strange political twist: KFC has aped Donald Trump's message to Kim Jong-un, in an attempt to feud with McDonald's.READ MORE

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.