Fake profiles boosted Brazilian ex-president Dilma

- Published

Former Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff speaks during a campaign rally in January

A BBC investigation has found that fake social media accounts and blogs were used to back the candidacy of Dilma Rousseff in Brazil during the 2010 election campaign. Rouseff won the election and was later re-elected before being impeached on corruption charges. She and her party deny any knowledge of the fakes.

He looked like an ordinary guy. Armando Santiago Jr was - apparently - 56 years old, married, and lived in Pocos de Caldas, a small city in south-east Brazil.

He was also a staunch supporter of presidential Dilma Rousseff and the Brazilian Workers' Party (known by its Portuguese initials, PT). On the social network Orkut - the most popular in Brazil at the time - Armando described himself as "a Brazilian citizen outraged by the criminal actions of the opposition in the election campaign." It was one of many broadsides against the main rivals of the PT, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB).

His influential blog was called "Seja Dita Verdade" ("Let the truth be said") and its stated mission was to transmit "transparent news".

"False e-mails against Dilma Rousseff are being spread," Armando wrote in one post. "I have, whenever possible, debunked them one by one in this blog."

But "Comrade Armando", as he was dubbed by other bloggers, was not a real person.

His blog and his profiles on Orkut and Twitter were administered by four people who were paid about 4,000 Brazilian reals ($1,400, £1,000) each a month to write and spread the Armando posts.

And Armando was not the only fake. During the 2010 election campaign, one company ran a network of false social media accounts in an attempt to boost the PT and Rousseff, according to whistleblowers inside the operation.

A screenshot of the "Armando Santiago Jr" profile in Orkut, where he described himself as "a Brazilian citizen outraged by the criminal actions of the opposition in the election campaign."

Meet the fakers

BBC Brazil interviewed three of the four people running the Armando blog. They say they were recruited by a political marketing firm based in Sao Paulo to carry out the work.

They say their job was to feed the blog with posts denouncing alleged rumours about Rousseff, as well as posts attacking her main opponent, Jose Serra, the PSDB candidate.

You may also like:

The blog also created false news stories which were spread by the team using other fake or "sock puppet" social media profiles - at least 131 of them on Twitter.

Although now, eight years later, the Twitter profiles are inactive, BBC Brasil has found that more than 80 of them still exist (in other words, they haven't been suspended or banned).

They include users like "Juliana Miranda", who wrote everyday tweets about her psychology course ("Freud is one of my passions") and others in support of the PT ("we want Dilma!"), in addition to retweeting Armando's tweets. Profile pictures were copied or stolen - in the case of "Juliana", from a Finnish blogger.

The Twitter profile of "Juliana M Miranda". The profile picture was taken from a blogger in Finland

The tactics were replicated in later elections. Last year, BBC Brasil revealed that fake profiles and misinformation were used in Brazil during the 2014 election, when a Rio-based company paid about 40 employees spread across Brazil to create and feed thousands of fake profiles, which were sold as a service to politicians.

It's extremely difficult to gauge what impact, if any, the fake accounts had on the 2010 election, which was won by Rousseff. She won re-election four years later before being impeached on corruption charges in 2016.

Brazil's current president is Michel Temer, who was once her vice-president. And in October 2018, the country will face another election.

False rumours destroyed - and created

Back in 2010, the Armando blog swatted down false rumours - for instance, that Dilma's running mate was a Satanist and that the candidate herself had a secret lesbian lover.

But those interviewed by BBC Brasil admit they also produced false news themselves. One post, for instance, reported that Serra supported abortion and that Vatican officials were considering excommunicating him.

"Jose Serra will be expelled from the Church," read the headline on one blog post.

The person who wrote the blog tells BBC Brasil that writers took steps to ensure that their fake stories were unfalsifiable, in this instance quoting "secret" Vatican sources.

"Who can verify that?" the writer says.

On presidential debate nights, the team would draw lots to determine who would be responsible for the "Armando" profile, because it involved so much work.

"The debate was like a World Cup final," one writer says. "It was a very stressful job."

A screenshot of a post from influential blog "Let the truth be said" falsely claiming that the Vatican was about to excommunicate presidential candidate Jose Serra

'Ectos'

The writers referred to their social media fake accounts as "ectos" - short for "ectoplasms". They included normal-looking "people" such as "Maria de Lourdes Coelho", a grandmother in northern Brazil who called herself "the voice of women in favour of Dilma." Another was "Mariza Villela", an entrepreneur who credited her success to "improvements of the country" under Dilma's predecessor and ally, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

The company bosses instructed the writers to create fake profiles with varying demographic profiles, backgrounds, professions, and writing styles, in order to reach different communities.

The profile of "Marcos Kaiowa" was created in an attempt to show that people from Brazil's indigenous community supported Rousseff

In the final stretch of the campaign, each employee maintained about 20 developed "ectos", in addition to the "Armando" profile.

They say there was no automation or use of bots - all of the posting was done manually. Profile photos were taken from various corners of the internet: from pages and blogs outside Brazil, and from dating sites. Most "ectos" were women with attractive profile pictures, deliberately chosen to hook in men.

For instance one fake account, "Cristina Morais", described herself as a "literature teacher, 25 years old, journalism student against traditional media outlets".

But her face belongs to 36-year-old Rio engineer Liana Soares, who lives in Switzerland.

When contacted by the BBC, Soares said she was upset at her picture being copied and pasted from her travel blog.

"If it's to manipulate public opinion, it's even worse," she says.

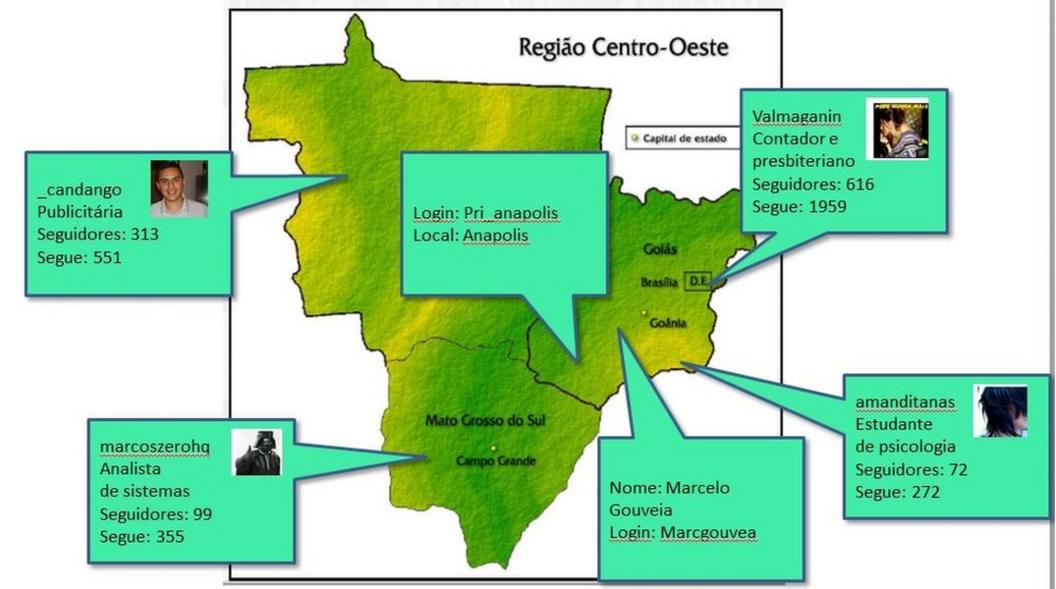

Fake profiles were designed to show widespread support. This internal PowerPoint presentation that BBC Brazil was given access to demonstrates how the writers aimed for a wide geographic distribution, in this case in the country's central region.

Allegations denied

The company who hired the employees the BBC spoke to is called Ahead Marketing. In an email, its owners denied having participated in the "production of fake news", but did not respond to a question about whether the company was engaged in creating fake profiles.

Ahead Marketing, owned by Gabriel Arantes Cecilio and, at the time, by Arnaldo Lincoln de Azevedo, said it could not comment on whether it was hired to work on Rousseff's 2010 campaign, citing internal confidentiality rules.

The company's website notes that it has participated "inside and outside Brazil" in "victorious campaigns for the Presidency of the Republic, State Governments and large capitals", without specifying particular candidates or elections.

There are no records of payments by the Rousseff campaign or the Workers Party to Ahead Marketing for work carried out during the 2010 campaign, although the agency was paid 234,000 Brazilian reals ($70,000; £50,000) by the campaign of Rousseff's ally Fernando Pimentel. Pimentel ran for Senate in 2010 and was one of the coordinators of Rousseff's campaign.

Dilma Rousseff denies she or her campaign ever hired someone to create fake profiles online.

Her press office told BBC Brasil they "neither contracted or authorized any services related to fake profiles and fake news in any of her campaigns in 2010 and 2014" and that she is "not aware of any of the companies or persons that act in this area, any action, initiative or action in this sense as part of their campaigns."

The Workers' Party, responding on behalf of Pimentel, told us they had "no knowledge about hiring any company for the creation and maintenance of fake profiles on Twitter in any election campaign."

There was a third person who co-ordinated the work, according to the former employees: advertising executive Ruy Nogueira Netto, who was also a link to the Workers' Party. The sources interviewed by BBC Brasil say they worked in his apartment in Sao Paulo.

Contacted via email, Nogueira Netto denied that he oversaw the false account team. He said he had met officials from Rousseff's campaign "to assess the internet" at his home, but had no knowledge of what they did.

Fakers' regret

Creating fake profiles to gain advantage or harm other people is illegal in Brazil, and legislation passed last year prohibits "the transmission of electoral content" through fake accounts on the internet. This rule did not exist in 2010.

Some of the false news writers now regret the work they did at the time.

"At the time, I thought that what we were doing was very important, that the blog also had the job of monitoring bad journalism," says one, "Today I think differently."

"I can hardly explain what I did in 2010," says another. "It wasn't journalism, it was something else, and it's something that can be very dangerous."

Do you have a story for us? Email BBC Trending, external.

More from Trending: YouTube's neo-Nazi music problem

A BBC Trending investigation has found inconsistencies in how YouTube deals with neo-Nazi music tracks which advocate murder and violence. The company admits that it has "more to do" when it comes to hate music videos.READ NOW

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.