Has #MeToo divided women?

- Published

Rose McGowan has become a key #MeToo figure

It has been the most visible feminist social media movement of recent times, but has #MeToo also created division between women?

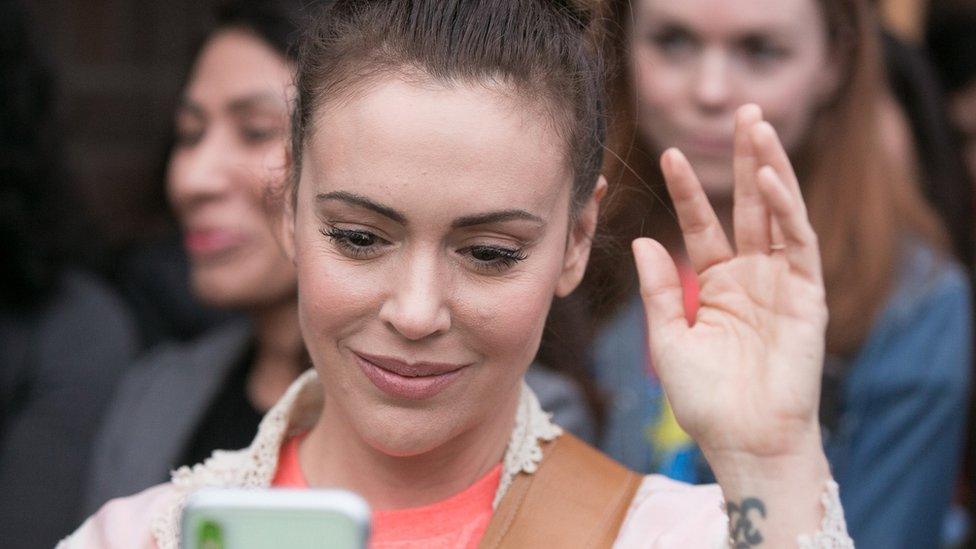

Few could have predicted the impact of a single tweet by actor Alyssa Milano in October 2017.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It came in the wake of dozens of allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, who has pleaded not guilty to rape and sexual assault charges.

Millions of women heeded Alyssa Milano's call, and thousands of stories were shared by women describing their experiences of sexual assaults and abuse online.

The moment was soon hashtag-ised into the #MeToo movement, which encouraged women to speak about about sexual harassment and abuse.

Alyssa Milano's tweet sparked a worldwide trend

You might also be interested in:

But as the allegations piled up against accused abusers and rapists, the phenomenon simultaneously exposed rifts and differences of opinion between women. There have been discussions about the aims of the movement: should it focus on workplace assaults, or be a much broader equality campaign? What tactics are useful? And what should happen when accusations turn out to be false?

One potential generational divide reared its head early on, with some older feminists decrying what they saw as a focus on victimhood. In essence, they were telling their younger counterparts to toughen up and get shrewder about the intentions of men.

In a much-discussed piece for The Atlantic, external, Caitlin Flanagan said women who were teenagers in the 1970s "were strong in a way that so many modern girls are weak."

Megan McArdle, a columnist for the Washington Post says: "I think there are situations in which women have more power."

Speaking to BBC Trending, McArdle says she believes the issue is "complicated".

"I think there are also lots of situations where the men do [have the power]. But I think we should teach those women to stand up and seize that power back."

Gender justice specialist Natalie Collins thinks that many younger women have been misled.

"I think young women have been told a lie that they can have equal power in sexual interactions with men. The reality is they don't."

Collins also believes the prevalence of pornography impacts more on the life of a younger woman.

"Porn culture has led her to have a particular understanding of what it means to have sexual interactions of what is erotic and what's not.

"The problem is she has lived in a culture which hasn't educated her that men and women are not equal, and men have power over women in nearly every interaction she's going to have."

On the other hand, it is possible that reports of a generational divide have been exaggerated. In a Vox/Morning Consult survey, external in March, there wasn't much difference in the attitudes of younger and older women about #MeToo - or their concerns about its potential negative effects

'Naive Fantasy'

Other women have raised concerns that the campaign's benefits will come mainly for white, Western women.

More than 10 years ago, before the present hashtag incarnation, African-American activist Tarana Burke first used the phrase "me too" in connection with a campaign against sexual assault.

Some have expressed concern that Burke and other ethnic minority women are being ignored.

Poet Asha Bandele told the website Afropunk, external: "I have my concern about the ownership of that movement publicly being in the hands of white women. I don't know that white women have ever led a movement that secured people outside of their own.

"And I also think about Tarana Burke who is the founder of #MeToo, not being given her proper space, in my opinion. She's not put on the cover of Time magazine for the movement she founded, she's put inside the pages."

But some have argued that the movement is adaptable, and that it will be interpreted in different ways across different cultures.

"Who can speak up about everything for everyone?" says author Kirsty Allison. "That's just a kind of naive fantasy."

The MeToo movement has inspired action in many countries, including this march against secretly filmed spycam pornography in South Korea

What's next?

Although social media mentions of #MeToo have declined since the explosion of interest following Alysaa Milano's initial tweet, the hashtag remains a consistent feature of online discussion. The movement shows no sign of going away.

The #MeToo hashtag was tweeted more than five million times in the last three months of 2017. And it was used more than two million times during a three month period between May and August this year.

"It's not like something like the fall [of the Berlin Wall] or like John Lennon getting shot. This is more like it's an ongoing moment," McArdle says.

"I think history will write this as a big cultural shift. Like many big cultural shifts in a couple of cases it may have, we're still calibrating. We had an old norm, we've gotten rid of it, what are the new ones? I think we're still trying to figure that out.

"We may look back and think in some cases we went too far and in some cases we didn't go far enough, we're still trying to figure this out but I think this will absolutely be seminal for women in the workplace. I really do."

Do you have a story for us? Email BBC Trending, external.

More from Trending:

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.

- Attribution

- Published20 June 2018

- Published21 June 2018