US election 2020: 'QAnon might affect how my friends vote'

- Published

The US election campaign is full of talk about the pandemic, the Supreme Court and police reform. But millions of Americans are tuning into an entirely different conversation.

"Saying it out loud, it just sounds crazy," says 24-year-old Jade Flury, reading out a recent text conversation she had with one of her friends.

She's talking to me on a video call while sitting at her kitchen table with the air conditioner on full blast, hiding away from the autumn heat in Houston, Texas.

Jade's friend has been taken in by Instagram videos about QAnon - an unfounded conspiracy theory that says Donald Trump is fighting a secret war against a deep state of satanic paedophiles in government, business and the media.

Jade Flury worries about the impact political disinformation has had on her friends

Despite her best efforts to counter false claims about "Democratic Party elites" running a child-trafficking ring, she's had to give up.

"He definitely feels like a 'sex ring' is still a thing," she says, "and asks why no reporters are putting as much effort into finding some underlying truth to this stuff as they are into trying to discredit it."

The truth is that reporters have looked into it. While the sprawling mess that is QAnon sucks in a few morsels of fact, its core is fiction, with no evidence to substantiate it.

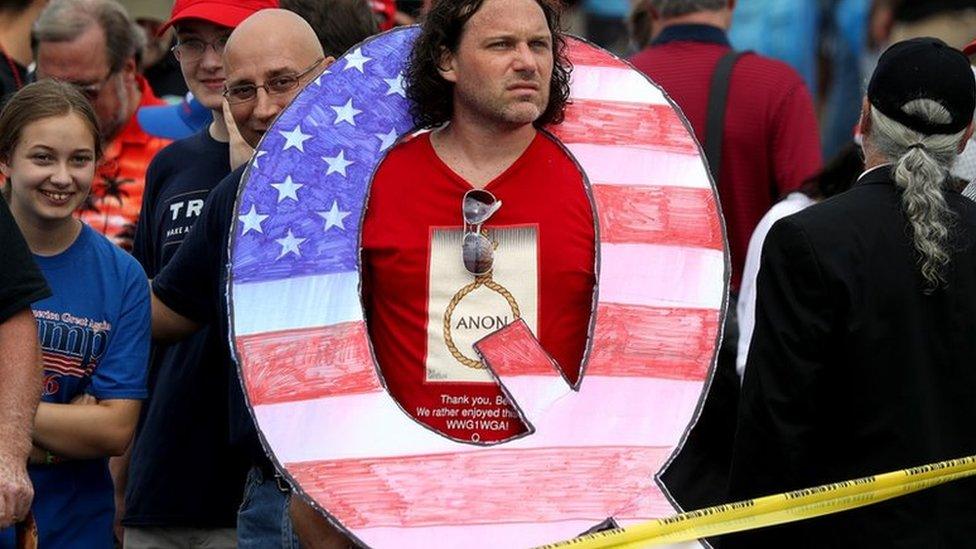

It was born on extreme message boards such as 4chan and 8chan - probably as a joke or prank - and rapidly spread among some of the president's most devoted followers.

BBC Trending

In-depth reporting on social media and online culture. Listen to our podcast - from the BBC World Service.

The 'rabbit hole' election

Jade's friend is one of the millions of Americans who are tuning in to a different election campaign than the one most of us hear about on the daily news. The "rabbit hole" election is filled with chatter about conspiracies, cabals, rumours and allegations.

Almost 1,000 miles (1,600km) from Houston, 68-year-old Tom Long uses social media quite differently. For one thing, he doesn't have an Instagram account. But his Facebook feed - and the group he runs which focuses on local politics - have also been overrun by conspiracy.

"When you start scrolling, you see all these crazy things that are posted and reposted that derive from QAnon," says Tom, "and they're all just getting crazier and crazier every day."

Tom is a retired autoworker who moved to the Florida coast from Michigan. Every morning - after a stroll down to the jetty at the end of his garden and a brisk 12-mile bike ride - he sits down to delete false and misleading posts on his group, Osceola Politics, external.

Tom Long regularly tries to remove political disinformation from the Facebook group he runs

They include videos and memes linking Joe Biden and the Democratic Party to unfounded allegations of child abuse, and posts claiming that President Trump is the only one who can save everyone from "elite child traffickers".

"It gets spread and spread and spread, even though it's completely false," he says.

Tom Long worries that his neighbours in the swing state of Florida are getting dragged into conspiracy theories

Reaching the mainstream

Of course, opponents of the president are also susceptible to baseless conspiracy theories. A number of pro-Joe Biden influencers, stepping into an information void created by the White House's mixed messages, recently spread fact-free rumours alleging that Trump's coronavirus diagnosis was faked.

But QAnon is by far the most popular conspiracy theory circulating online today. BBC research found that QAnon has already generated more than 100 million comments, shares and likes on social media sites this year, a trend that ramped up over the summer.

On Facebook, the biggest QAnon groups have generated 44 million comments, shares and likes. By comparison, that's about two-thirds the number of reactions generated by Black Lives Matter groups - a movement that has received a huge worldwide wave of media attention.

Initial attempts at crackdowns by social media companies appeared to slow the spread - but supporters of the conspiracy theory soon used new hashtags to evade measures and reach the average Facebook, Instagram or Twitter feed.

Although true believers are still a fringe group, they are spreading the word - and fast. In March, a Pew Research Center survey found three-quarters of Americans hadn't heard of QAnon, external. By September, the uninitiated had dropped to about half of all Americans, external, according to Pew, a nonpartisan think tank. Around 9 percent said they'd heard "a lot" about the movement - but even that relatively small number means that millions are tuning in.

A number of Republican candidates on the ballot in November have expressed sympathy for or even outright belief in QAnon ideas.

Experts say the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown measures explain part of the rise in popularity. QAnon influencers took advantage of fear, uncertainty and doubt - and the fact that many people were at home, worried, and living more of their lives online.

QAnon theories have increasingly merged with coronavirus conspiracy theories, giving believers simplistic explanations to help them through difficult times.

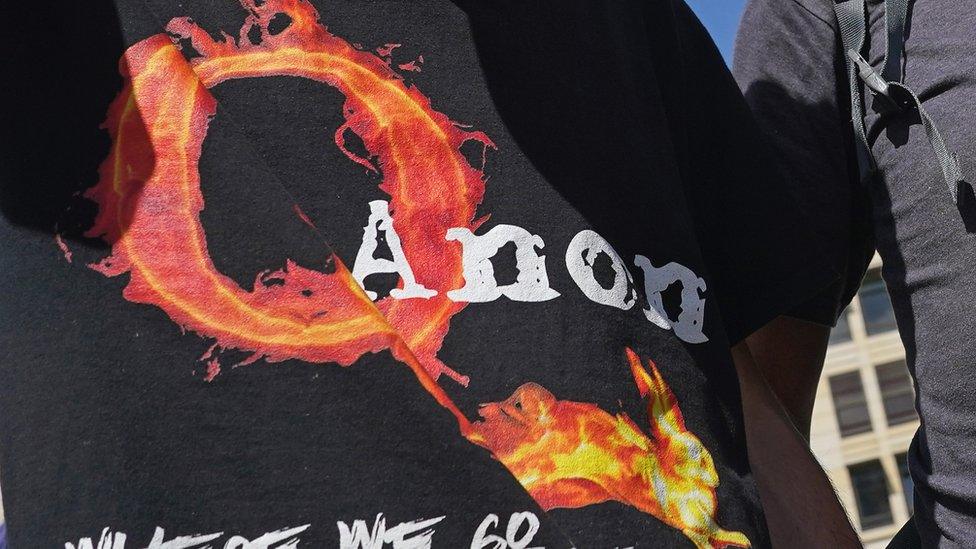

"Qanon is a very pervasive conspiracy theory with a lot of very cult-like tentacles that can really grab onto people's minds when they spend a lot of time online," says Michael Edison Hayden, senior investigative reporter at the Southern Poverty Law Centre, which tracks extremist groups.

Experts also say that QAnon is becoming so successful in worming its way into the mainstream that some people profess its beliefs without realising where they came from.

Whitney Phillips, an assistant professor at Syracuse University who has spent years researching conspiracy theories, says that even though a relatively small percentage of Americans buy into the idea of an "elite satanic child abuse ring", other ideas popular in the QAnon movement are rapidly taking hold.

"One of those is the deep state - which holds that there is essentially a shadow government within a government that's trying to undermine Trump," she says. QAnon supporters didn't invent the idea, but they have been instrumental in its spread.

Generation Z, Generation Q?

Jade Flury has been busy recently - she's a young journalist keen to get back to the studio where she works.

Most of her conversations with friends have been about the pandemic that's been stopping her getting on with life as usual. But she's concerned that conspiracy theories might change how her friends engage with politics.

"It's definitely going to impact their voting. Some of them now think the Democrats are evil. Others think Donald Trump is the saviour.

"And some people truly believe that their vote just doesn't count at all because the 'elites' control it," she sighs.

Undermining democracy?

Whitney Phillips argues that the danger of QAnon is actually much larger than its influence on the votes - or non-votes - of individuals. QAnon, she says, prepares the ground for a wholesale rejection of democracy itself, noting that President Trump himself has refused to confirm that there will be a peaceful transfer of power if he loses.

"If a significant percentage of the American people are primed not to accept the outcome, and if Trump loses, that is going to pose challenges that I can hardly wrap my mind around."

You might also be interested in:

Social media companies seem to be paying attention. Over the summer, Facebook and other major networks took action against QAnon - including banning hashtags and accounts, and restricting the spread of some posts.

Facebook went even further this week, announcing a stricter ban on QAnon content.

But the conspiracy theorists have adapted. After the summer purge, many shifted to using more innocent-sounding hashtags such as #SaveOurChildren and #SaveTheChildren - the latter having no relation to the charity of the same name. Those hashtags drew in concerned people who would never dare venture onto the swamplands of 4chan or 8chan.

I recently asked Nick Clegg, the head of Facebook's global affairs and communications team, whether the company could do more, and whether they'd acted too late.

He denied that was the case and pointed to the large number of posts and groups that Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram had already taken down. But the new, more strict measures, which ban all QAnon accounts, pages and groups, came into place soon after. Facebook also said they will specifically tackle content using hashtags like #SaveOurChildren.

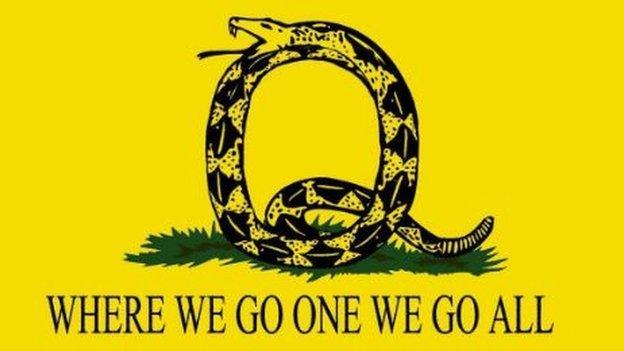

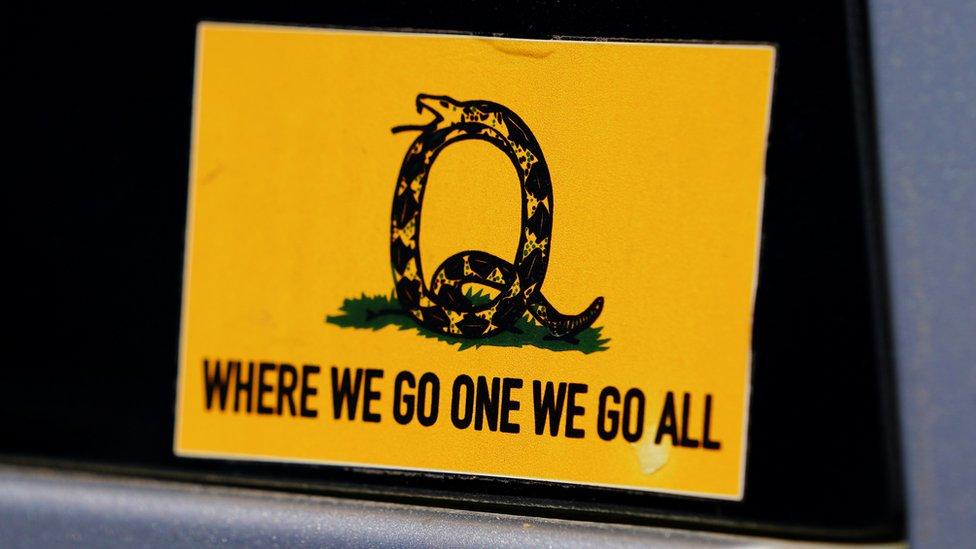

"Where we go one we go all" is a rallying cry for QAnon followers

Whether action by the social media companies will have any effect on QAnon's popularity will be an open question for some time. But for Tom Long in Florida, the damage has already been done. Conspiracies are yet another thing tearing America apart - making him feel, he says, as though he lives in an entirely different country than the one he grew up in.

"There was a time when both sides would have to cooperate with each other to get things done," he says. "That's not the way it is in this country anymore."

With additional reporting by Ant Adeane and original research by Shayan Sardarizadeh, BBC Monitoring.

Subscribe to the BBC Trending podcast or follow us on Twitter @BBCtrending, external or Facebook, external.

- Published22 July 2020

- Published6 January 2021

- Published3 September 2020

- Published20 August 2020

- Published7 August 2020