The truth about 'medbeds' - a miracle cure that doesn't exist

- Published

One TeslaBiohealing facility is in a converted motel in a small town on the Mississippi River

Strange corners of the internet are awash with chatter about miracle devices that can cure nearly any ailment you can think of using the power of mystical energy. Some companies charge thousands for these "medbeds" - but their claims are far from proven.

A converted motel in a small town on the Mississippi River seems an unlikely home for a world-changing technology - what a flyer in the mostly deserted lobby calls a "new wave of scientific healing".

But since last summer, this building in East Dubuque, Illinois - three hours west of Chicago - has been outfitted with medical devices that supposedly imbue patients with "life force energy". It's one of a number of locations run by Tesla BioHealing - no relation to the car company - dotted around the US.

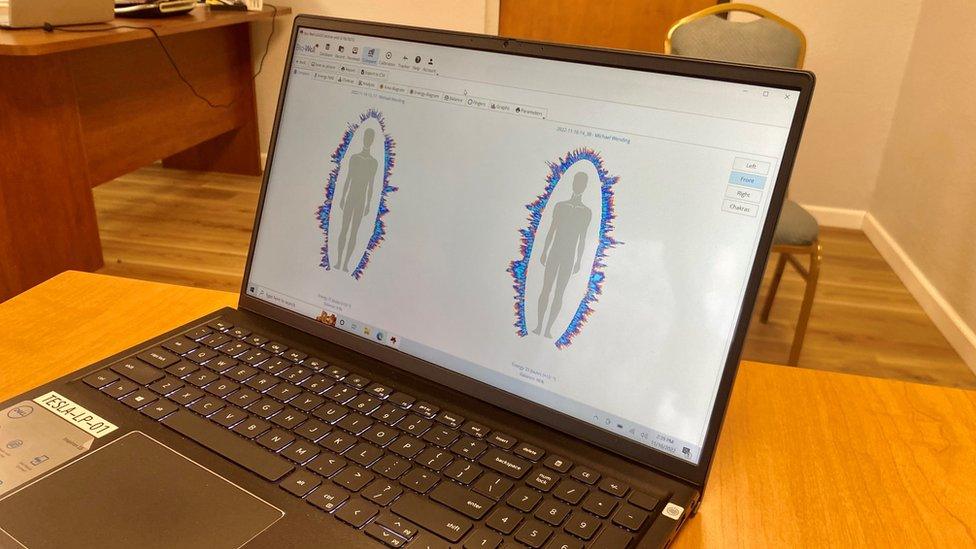

I tried out a medbed on a recent gloomy weekday afternoon. After being greeted at the front desk, a doctor tested my energy levels by having me place my fingers inside a metal box.

Then I was ushered into one of the rooms, mostly unchanged from its motel days, and I waited for "pure biophoton life-force energy" to stream into my body.

The company has placed its containers underneath ordinary beds in its facilities

The idea of medbeds - short either for "medical beds" or "meditation beds" - has become increasingly popular on fringe medical channels, on mainstream social networks and chat apps.

But people have very different ideas about what they actually are. Some insist that the technology is secret, unlikely to be encountered by mere mortals, hidden from the public by billionaires and the "deep state". The more conspiratorial theorising includes speculation about "alien technology" and bizarre claims like the idea that John F Kennedy is still alive, strapped to a medbed.

A separate, more earthly avenue of thought holds that medbeds are very real and publicly available, just not part of the medical mainstream.

It's this strand that Tesla BioHealing and a range of other companies are staking their rather expensive claims on. Tesla BioHealing offers home generators for prices up to $19,999 (£16,500), although an hour in one of their medbed motel rooms will only set you back $160 (£130).

But even in the consumer-focused medbed world, where there is no talk of aliens or JFK, there's disagreement about what a medbed actually is. And there's a very good reason for that, says Sara Aniano, a disinformation analyst at the Anti Defamation League's Centre on Extremism.

"It's really hard to define something that doesn't exist," she says.

Ms Aniano has been researching the spread of medbed chat online, and as part of her inquiries signed up for trial with a different medbed company, 90.10.

"The trial is nothing," she says. "It tells you to lay on your bed and think really hard about the medbed."

"In their defence, they do list on their website in the very fine print down at the bottom that the medbed is not meant to treat or diagnose illnesses," she says.

It's a common disclaimer that we saw used in some form by just about every company offering a medbed-related product. Even though companies put out long lists of ailments that can supposedly be helped by their technologies, and provide testimonials from satisfied customers, they say that their products are not meant to replace treatments by a qualified doctor.

Tesla BioHealing is no exception. The top of the company's website clearly states: "We cannot diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease or condition."

And yet their promotional material states: "Many people note improvements in their wellbeing even after only an hour of resting on a Tesla MedBed." They also make a number of specific, unsupported claims about particular diseases.

Tesla BioHealing's website comes with a disclaimer at the very top of the page

The staff at the Tesla BioHealing motel in East Dubuque told me about legions of customers with all manner of ailments, all of whom they said had been helped by medbeds.

But in my room, I felt nothing more than curiosity and a slight sense of unease as I gazed out the window at a mostly empty car park. The Tesla Medbed cannisters were sealed in wooden boxes and a bedside table.

Cutting short my hour, I returned to the doctor's office where she repeated the test with my fingers in the metal box. Sure enough, my energy, as measured by the doctor's laptop, was already rising.

But neither the doctor nor anyone else at Tesla BioHealing could tell me what was inside the medbed cannisters themselves.

Some enterprising customers have taken it upon themselves to try to find out. We came across a TikTok video where an upset punter appears to have opened up a cannister, only to find a concrete-like substance.

"For anyone who's thinking about buying one of those Tesla biohealers, don't waste your money," she says.

The company wouldn't be drawn on what active ingredients, if any, are inside the cannisters. But they told us in an email: "There is much more going on with our technology than meets the eye."

And while they said the Tesla cannisters were not intended to replace a doctor's care, they also made further claims of cures and said: "Health benefits are priceless."

The Tesla BioHealing generators - with unknown contents

Both Tesla BioHealing and 90.10 pointed us to thousands of positive customer testimonials. And despite the prominent claim on the company website that 90.10 offers "Quantumfrequency medicine with scientific proof", 90.10 chief executive Oliver Schalke told us: "It is not a medical product and was never intended to be."

How, then, are the medbed companies allowed to offer their products, hint at miraculous effects, but escape any regulatory oversight?

Several companies, including 90.10 pictured here, advertise medbeds or related products for sale

Dr Steven Barrett, a retired psychiatrist who has been investigating questionable claims for decades, says the health care regulator in the United States - the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) - is partly to blame.

"FDA registration is required by any manufacturer who wants to market products, but it just means that you've notified the FDA that you exist," he says.

Tesla BioHealing and other companies advertise that they are FDA registered - but that is next to meaningless.

"FDA registration says nothing about whether a device is useful," says Dr Barrett.

When it comes to making vague claims about general well-being or unprovable statements about increased energy, authorities "do almost nothing about it", he says.

He speaks with a note of weariness, perhaps because of a lack of "biophotons" but more likely the result of spending decades tracking dubious health claims.

"Do I think that exposure to whatever it is that they're giving you in the bed is going to make you more energetic? I seriously doubt that," he says.

Indeed, as I began a long evening drive home from East Dubuque under cloudy skies, I felt distinctly lacking in life force energy.

With reporting by Elizabeth Hotson and Shayan Sardarizadeh