Lotus builds hydrogen fuel cell taxi for London 2012

- Published

The Lotus-built cab is much quicker than diesel-powered versions

The sound of squeaking plastic parts is a minor irritant as the black cab surges into a sharp corner, its body leaning heavily.

Normally, at high speed, the rattling would have been drowned out by a rumbling, whining diesel engine.

But this taxi is different.

It is a hydrogen-powered London cab, developed to showcase zero exhaust emission vehicles during the 2012 London Olympics.

The taxi has been put together by Lotus, a UK company more famous for its Formula 1 team and for making sports cars such as the Elise.

Long-range electric motoring

From the outside, the taxi looks like any other black cab and it weighs as much too - a whopping 2.6 tonnes.

But driving it at the Lotus test track in Norfolk feels completely different as it accelerates from 0-60mph (0-100km/h) in 15.5 seconds - slow compared with most cars, but a full seven seconds quicker than an ordinary black cab.

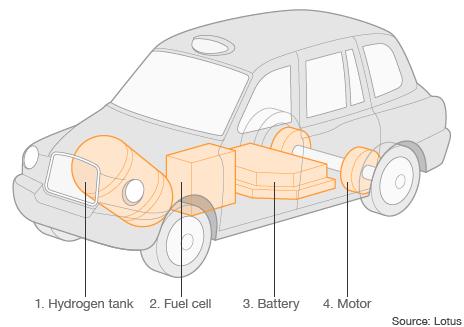

Under the taxi's familiar exterior - within its generous bulk - the truly special bits are hidden.

The back wheels of the taxi are powered by two electric motors - though it is not an electric car in the conventional sense of the term.

Dr Kells says fuel cells deliver electricity, similar to the way a battery does

Yes, the taxi has a lithium polymer battery that delivers electricity to the electric motors, but this is not its main source of power.

The cab also has a stack of fuel cells that convert energy from hydrogen, which is stored in a tank under the car's bonnet, into electricity.

The electric motors can be powered by either the fuel cell system, or by the battery, or by a combination of the two.

During braking the battery, which is located in the middle of the taxi under the floor of the cabin, is recharged by two sources:

surplus electricity created by the fuel cells is sent to the battery

kinetic energy captured during braking is sent to the battery from the back wheels, via the electric motor.

With two different power sources - fuel cell system and battery - the taxi could be described as a hybrid vehicle, but again, not in the conventional sense of the term, which usually refers to petrol-electric hybrids.

Technology showcase

The point of all this is to create a car with zero emissions; or rather, the taxi does not have an exhaust pipe as it only emits water vapours.

Now, whether that makes it green is another matter.

Hydrogen is made by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen, but this process is energy intensive.

If it is done with the help of renewable energy sources such as wind turbines, the car will be green, though in practice the hydrogen is more likely to be produced using fossil fuels such as gas.

Filling up the hydrogen tank takes just five minutes

So rather than being seen as a green car, it is perhaps more apt to see the taxi as a marketing vehicle.

"The black cab is a good tool for us to demonstrate the technology," says Dr Ashley Kells, programme manager at Intelligent Energy, the company that developed the cab's fuel cell system.

A fuel cell is "very much like a battery" in that it delivers electricity, according to Dr Kells, though there is one major difference: recharging a battery is a slow process, whereas refuelling a hydrogen tank is not.

"And as long as you keep on providing fuel for the cell, it will keep on providing power," he explains.

Five-minute fill

The electric motors are powered by either the fuel cells or the battery

For London's cabbies, the fuel comes in the form of gaseous hydrogen that is pumped into a tank under the taxi's bonnet.

"The fuelling is very quick," says Dr Kells as he demonstrates how the fuel connector is fixed to the taxi whilst fuelling to make sure the hydrogen gas does not leak.

There is another crucial difference between fuel cells and batteries, he adds, namely "the energy density of a fuel cell system, which is a lot greater than current battery technology".

In other words, electric cars powered by fuel cells carry much less weight and deliver much greater range.

One tank of gaseous hydrogen gives the taxi a range of at least 160 miles, or up to 240 miles if driven carefully, so the cabbies should be able to do what they do in conventional taxis, namely fill up in the morning then drive all day.

"They go to the filling station and five minutes later they've got a tank full of fuel and a copy of the Daily Star from the garage," says Dr Kells.

Lotus is better known for its sports cars

As a marketing vehicle, the taxi has a role to play in the enormous PR machine that has grown up around the 2012 London Olympics.

By then, there will be a handful of hydrogen fuel cell taxis in London, served by six hydrogen filling stations that they will share with at least five hydrogen fuel cell buses.

"We're not just doing this as a one-off," says Dr Kells, insisting the project offers "a real, tangible solution for 2020".

By then, London Mayor Boris Johnson wants every taxi operating in London to deliver zero exhaust emissions.

However, for engineers at Lotus, who are more accustomed to working with ultra-light cars such as the 1.1 tonne Lotus Elise, this is just the beginning.

They hope to push the project further and develop lighter, more efficient taxis in the future.

"I would really have liked to do it with a new chassis to make it an optimally system," says Steve Doyle, chief engineer, hybrid and electric vehicle integration, Lotus Engineering.

Dr Jon Moore, communications director and one of the founders of Intelligent Energy, agrees.

"If we can do it with this, we can do it with anything," he says.

How the taxi works