'Flying' submarines plumb hidden depths

- Published

Two-thirds of the earth is underwater. We glide over the surface of the oceans, but we still have very little idea what is going on even a few metres down.

We spend billions sending craft and people into space, but we do not really know what happens under the waves.

One man who finds that more than curious is Graham Hawkes, a beneath-the-sea maverick who has been working on underwater craft for most of his life.

It is a lonely, driven quest, relying rather dangerously on the engagement and backing of a few wealthy enthusiasts.

Born in London, Mr Hawkes learnt his engineering expertise in the defence industry, working initially on torpedoes in Norfolk, England.

In the 1980s he went to the US, working on oil and gas exploration before setting up on his own, with the aim of bringing a new clarity and purpose to manned exploration of the deep ocean.

Atmospheric pressure

In his harbourside workshop just across the Bay from San Francisco, Mr Hawkes shows me some of the results of his years of work: submersible craft looking much more like planes than conventional submarines. There are various versions, all called DeepFlight.

One of those I look at has a 12-foot (4 metre) wingspan. It is beautiful, quiet and light enough to load and unload from relatively small support vessels. It is designed to explore the deepest part of the sea, the Mariana Trench in the Western Pacific somewhere between Japan and Papua New Guinea.

The Trench is much deeper than Mount Everest is high - almost 7,000 feet (2,100m) deeper. The water pressure down there is a thousand times the atmospheric pressure at sea level.

That is where Mr Hawkes wants his underwater flying machine to go.

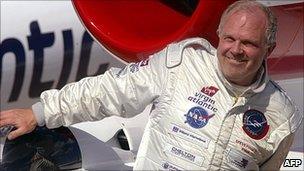

The adventurer and businessman Steve Fossett had hoped to set a new world record

So did the late Steve Fossett, the American multimillionaire adventurer with 115 world records or world firsts to his name.

He died in an air crash in the Californian mountains in 2008, just as Mr Hawkes was within four weeks of putting the DeepFlight Challenger through its first tests.

It was being built for Mr Fossett to claim another record - the first solo exploration of the Mariana Trench.

The US Navy two-man bathyscaphe, The Trieste, got to the bottom of the Trench in 1960.

Two unmanned vessels have since been down there, but a one-man flying machine would be a very different proposition.

Pioneer

Steve Fossett's untimely death was a big blow to Mr Hawkes and the DeepFlight team.

Now they need another multimillionaire with similar ambitions to take on the challenge.

The submersibles are beautiful machines, breathtakingly simple to operate. They treat water like air, says Mr Hawkes.

From early on, he has had the reputation of making things happen. But being a deep sea pioneer is not easy.

And if we are properly to survey the two-thirds of the world that is scarcely known to us, clever robots will do most of the work down at the ocean bottom.

It is much safer, and cheaper, than sending humans.

And there may be great mineral and other riches to be found, to say nothing of a host of unknown life forms.

But submarines and bathyspheres and robots do not catch the imagination in the way that DeepFlight does.

For one thing, they do not fly.