Migrants feel recession aftermath

- Published

Fewer migrants took up work visas in the US in 2009

Migrant workers are suffering worst in the aftermath of the global recession, according to a special report commissioned by the BBC World Service.

Foreign workers in developed nations are more likely to be jobless than their native-born counterparts, as the employment gap widens between the two.

At the same time, immigration to developed countries has slowed sharply.

The research was done for the BBC by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), an independent agency in Washington.

But despite the job losses among migrant workers, the overall amount they send in remittances to their families back home fell less than expected last year and is expected to bounce back.

Migration stalls

"Overall immigration to developed countries has slowed sharply as a result of the economic crisis, bringing to a virtual halt the rapid growth in foreign-born populations over the past three decades," the report says.

This has caused a notable decline in illegal immigration. The number of foreign workers caught trying to enter the EU illegally by sea fell by more than 40% from 2008 to 2009 and is still falling.

Not so many illegal migrants are trying to reach the EU by sea

At the same time, the number of illegal migrants from Mexico stopped at the US border went down by roughly the same amount.

However, legal migration has also been hard hit. Immigration to the Irish Republic from new EU member states in Eastern and Central Europe fell by 60% from 2008 to 2009.

Over the same period, the US saw a 50% drop in the number of visas issued to low-skilled seasonal workers, such as fruit and vegetable pickers.

But those migrants who are already established in developed countries are having a tough time.

In Spain, for instance, the recession has had profound effects on the immigrant population, the MPI says.

At the end of 2007, the report says, 12.4% of immigrants in Spain were jobless, as against 7.9% of native-born Spaniards.

But by mid-2010, after Spain's construction boom turned to bust, those figures had gone up to 30.2% and 18.1% respectively.

"Immigrants represent one in six workers in Spain's labour force, but now account for nearly one in four unemployed," the MPI says.

This is partly because migrants tend to work in areas of the economy that are more vulnerable to recession. But it still presents a serious problem for the government in Madrid, which is struggling with the highest jobless count in the 16-nation eurozone.

'Resilient' migrants

The experience of the UK as highlighted by the report is rather different.

Eastern European communities have become established in the UK

As the MPI points out, robust economic growth and greater openness to economic migration pushed the UK's foreign-born population to the historically high level of 13% by the time the credit crunch dawned in 2007.

But it finds that Eastern and Central Europeans who arrived from 2005 onwards have been relatively unscathed by the rise in joblessness.

"The boom-time immigrant influx has not led to catastrophic immigrant unemployment, in large part thanks to Eastern European workers who helped to fuel the boom but proved relatively resilient to the downturn," the report says.

It also says there are signs that Eastern Europeans are putting down more permanent roots and establishing families in the UK, "in contrast to the prevailing image of the young, single and highly labour-motivated Eastern European worker."

Not all the UK's immigrant groups fared as well, though. Those from Africa and from Pakistan/Bangladesh saw their unemployment levels peak at 14% and 17% respectively a year ago, before the economic recovery brought some relief.

Lower transfers

On the whole, migrants are sending nearly as much cash back to their families in their home countries as they used to.

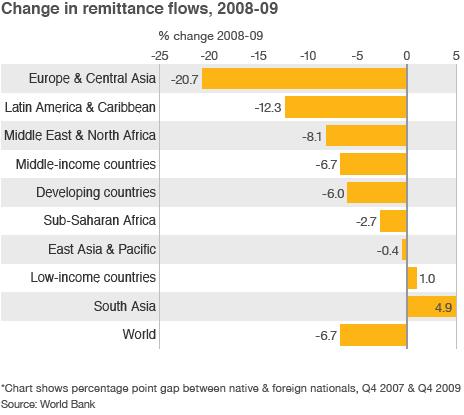

Remittance flows, which had been going up sharply before the global recession, fell 6% in 2009 and are expected to grow 6% this year.

However, that total masks big divergences in the performance of individual regions.

While remittances to South Asia went up by 4.9% last year, those to Europe and Central Asia shrank by 20.7%, while the relatives of Latin American and Caribbean migrants received 12.3% less.

"It is clear that the flows of money from migrants to their countries of origin are dramatically less than they would have been in the absence of the global economic crisis," the report says.

New destinations

The MPI notes that the global downturn "has strengthened the voices of those who have always been sceptical of immigration's benefits".

Between 2008 and 2009, the US and several European countries saw an increase in the number of people who considered immigration more of a problem than an opportunity, the report observes.

However, those countries may not be primary destinations for the migrants of tomorrow in any case, it argues.

"Although the number of migrants worldwide is projected to grow in coming years, developing nations - not traditional immigrant destinations in more developed regions - are expected to drive much of this growth, claiming an increasing share of the world's migrants," it says.

- Published28 July 2010

- Published27 July 2010