Currency intervention's mixed record of success

- Published

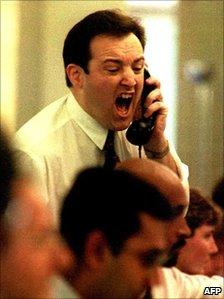

A currency trader in London shouts orders as the pound continues to fall after the UK's intervention in currency markets in 1992

The law of unintended consequences is rarely as true as when applied to currency interventions.

Japan's surprise move to weaken the value of the yen was a bold move, but the government is well aware that such actions have a mixed record of success.

Earlier this year, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) began large-scale buying of euros.

The aim was to halt the inexorable rise of the Swiss franc and to maintain the competitiveness of the economy.

But the franc continued to appreciate, and in July the currency was at an all-time high against the euro.

Since then the SNB has been offloading parcels of euros, pushing the currency even lower against the franc.

Central banks rarely telegraph their plans to dip into the market. And details about the scale of their interventions are even rarer.

This information vacuum is filled by rumour, and since July the SNB has been dogged by periodic speculation that it is offloading another tranche of euros.

And this helps up the franc. The exercise has been self-defeating.

Yet, despite plenty of scepticism among analysts as to whether intervention works, policymakers see it as an essential part of their armoury.

In the past couple of years Mexico, Poland, Indonesia, and Russia are among countries that have acted to protect their currencies.

Last year Russia is thought to have spent $210bn to maintain the rouble at a rate of 41 roubles against a basket of dollars and euros. The rouble is now at 34.86 versus the basket.

The Swiss and Russian examples suggest their actions backfired. Yet, who knows how strong or weak the franc and rouble would be if there had been no intervention.

Humiliation

One definite example of a failure of intervention was in 1992, when the UK attempted to shadow the German Deutschmark and stay in the Exchange Rate Mechanism.

Fund manager George Soros made a lot of money when Britain's currency intervention failed

In just one day, the UK spent billions of pounds defending sterling's value. But the foreign exchange markets knew it was pointless, and kept selling.

Britain suffered a humiliating defeat, and a little-known currency trader called George Soros made a lot of money.

Of course, central banks intervene for different reasons. Britain wanted to defend sterling, whereas Switzerland wanted to weaken the franc.

And influencing the supply and demand of currencies is only one reason central banks intervene.

It can also send important signals about future monetary policy and policymakers' assessment of whether a currency is divorced from economic fundamentals.

But Japan's previous attempts at intervention, six years ago, failed to stop the yen's appreciation despite a 15-month spree of buying dollars.

Tohru Sasaki, currency strategist at JP Morgan, said in a research note last month: "There is no historical case in which [yen] selling intervention succeeded in immediately stopping the pre-existing long term uptrend in the Japanese yen."

This latest action at least had the desired result on day one - weakening the yen against the dollar by about 3%.

Economist Nouriel Roubini argues that most major countries want a weak currency, not just Japan

But this is a long-term game, designed to push up the prices of imported goods and lift Japan from the deflationary spiral that has damaged the economy for years.

The success of this plan will not be known for some time.

One reason that Japan's move took the markets by surprise was that currency traders did not expect intervention - if at all - without support from partners in the G7 group of leading economies.

Jean-Claude Junker, chairman of the Eurogroup of eurozone finance ministers, told reporters: "Unilateral actions are not the appropriate way to deal with global imbalances."

Asian impact

Economist Nouriel Roubini said history shows that co-ordinated action by central banks works better that unilateral action.

But it does not appear that the US Federal Reserve or European Central Bank are involved, Mr Roubini said. What's more: "We are in a world where everyone wants a weak currency."

Japan's move pushed the dollar higher, something Washington wants to resist as it makes US exports more expensive.

Following Japan's move, the dollar also rose against the currencies of Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and, crucially, the Chinese yuan.

The US has accused China of artificially dampening the yuan the boost exports, something Beijing rejects.

Analysts are now asking if central banks in these Asian countries will weaken their own currencies to counter Japan's impact on their economies.

It is a reminder that central bank interventions do not happen in isolation. When a currency is sold, another must be bought.

- Published15 September 2010

- Published15 September 2010