Real-time computing goes from Wall Street to High Street

- Published

Ports, such as Rotterdam, are using real-time software to better manage the chaos of ships arriving and leaving

Earlier this year Vishal Sikka was sitting in a cafe, chatting with the chief technology officer (CTO) of a major European consumer products company.

They were in Berlin. It was a sweltering day, with the thermometer soaring above 37C (99F).

"The fundamental problem we have, Vishal, is predicting demand," the executive lamented as he looked onto the square. "For example, ice cream."

If the company could monitor sales of ice cream - or bottled water or sun tan cream - on hot days like this one and then gauge future demand, he said, it could alter the way the company behaved. "How much?" Mr Sikka asked.

"Just six days like this a year would change the profitability of our company," the CTO replied.

'Truly transformational'

Mr Sikka, an executive board member and responsible for technology and innovation at SAP, the world's largest maker of business software, went home and told his teams to design software that would allow that company to follow its customers in real-time and analyse their patterns of behaviour.

This involved tracking the company's 400 billion of retail transactions a year - that is 40 terabytes of data - as they are coming in. The prototype is almost ready to be trialled.

"You are posing questions in real-time to the data," Mr Sikka says, "and not only that, but the actual data you are posing questions to is also updating in real-time."

Credit Suisse has a real-time currency trading app for Apple's iPhone and iPad

"This is truly transformational," he says. "That's what all our customers are telling us."

Real-time - the act of responding to events as they happen - is changing the way that the world behaves.

Smartphones put everyone a click away from the Internet. Location-based services like Facebook Places and Foursquare let others see exactly where you are. Twitter - which generates in two minutes the amount of text found in the entire works of William Shakespeare - gives live and instantaneous reactions.

But in the business world, new technologies allow companies to see what their customers are doing - to the latest millisecond.

Bank innovation

In technical jargon, the software that allows this to happen is known as complex event processing (CEP). Though one of the innovators behind the technology, Giles Nelson, does not entirely like the term.

"It makes people think its more complex than it actually is and puts them off," Dr Nelson says. "It's really quite simple.

"Speeding things up is what's happening across all industries," he says.

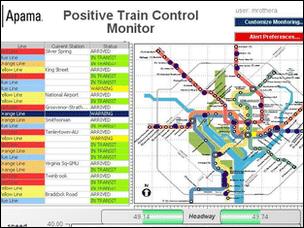

Dr Nelson, the deputy CTO of Progress Software, invented the technology behind its CEP platform, Apama, while a PhD student at Cambridge in 1993. Similar work was also being done in the US.

"In the late Nineties, there was an awareness among academics that things would be going in the direction of real-time," says Mark Palmer, the head of Massachusetts-based StreamBase Systems, whose technology is derived from research at MIT and other leading US universities.

The first users of CEP were banks - not only stock traders but the more exotic instruments that were starting to take off, such as options, futures and other derivatives.

The software uses mathematical algorithms to track stocks as they move. Take, for example, two oil stocks that move in tandem. Banks can track the two stocks over, say, a 10-second period. If one stock moves even a tenth of a percentage point, it automatically buys the other.

'Practically museums'

The use of so-called "algo trading" has contributed to huge increases in the volumes of trading over the past decade, as much trading is automated.

"It used to be that there were people in London and New York on trading floors doing this," Mr Palmer says. "Those days are over. Those floors are practically museums."

Trading in the currency markets has grown by 20% in the last three years to $4 trillion a day, with London by far the world's biggest hub, the Bank for International Settlements recently said.

London-based spread-betting firm CMC Markets - which allows non-specialist retail investors to make bets on the financial markets - has an average trading volume of $10bn a day and once used Apama before abandoning it for StreamBase.

Mark Palmer's StreamBase software is used by many of the top banks

And Swiss bank Credit Suisse now has an application for the iPhone and iPad that allows its clients to make live options trades on the go using its Merlin currency trading platform.

"Algo trading was less than 10% of trading at banks," says Mr Palmer. "Now it's 50 to 70% of trading." Two-thirds of the top banks use CEP software now.

The software has also been blamed for exacerbating the financial crisis. Computer programmes automatically sold stocks as fear spread in the markets, because their algorithms have built-in "sell" orders. CEP was also blamed for the sharp drop in US shares on 6 May - when the Dow Jones index fell by almost 1,000 points in a matter of minutes.

Yet the use of the software is spreading. The London Stock Exchange - through its Turquoise trading platform - uses Apama, as does the Financial Services Authority, which uses Dr Cohen's software to monitor fraud.

HSBC uses software from US business analytics firm SAS to approve in real-time every single credit card transaction.

Future uses

Now, real-time processing software has spread beyond Wall Street and the City to other industries.

Apama software is used to power the real-time capabilities of many large companies

Apama is used by customers in the Netherlands - Rotterdam has the largest port in Europe, with an annual through-put of about 400 million tons - to manage the logistics of ships, which often fail to arrive on time and spend hours waiting to dock and unload at ports, wasting fuel, money and time.

Rather than wait until the end of the day or week, supermarkets and other large multinational retailers use the software to monitor their stock inventories in real-time.

Telecoms companies are using it to manage the strain on their networks. Mobile phone firm Three, in Italy, is using Apama to test whether it can offer customers faster music downloads - for a price - when network usage is low.

SAP's software is also being deployed on offshore oil rigs and even in hospitals around the world. This allows diabetic patients, for example, to have their blood sugar levels monitored and insulin administered if it gets dangerously high.

StreamBase has discussed using its software to monitor patients in hospital, looking for abnormalities and alerting doctors immediately, before the situation becomes critical.

Mr Sikka says a large British gas company recently started using its software to analyse the data from smart meters of 60,000 customers in London, and discovered that there was a spike in energy usage around 7pm.

The firm changed its tariffs to account for that.

Future applications that are being discussed include the military, such as real-time monitoring of troop and tank movements. StreamBase is already used by the US National Security Agency to monitor security threats.

"It's difficult to think of an industry that isn't affected by real-time," Mr Palmer says.

- Published29 September 2010

- Published14 May 2010

- Published1 September 2010