Colour-code clue to Brazil's inflation past

- Published

Shopping in Brazil is less nerve-racking since inflation was tamed

If you want to know what living with hyperinflation in Brazil used to be like, an arcane system still used in many of the country's smaller record shops provides a clue.

In place of a price-tag, each of the CDs on display in the racks has a small, round label attached. These come in a variety of colours.

To find out how much it actually costs, you have to consult a chart on the wall which quotes different prices according to the different colours of the stickers.

The reason? During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the price of everything in Brazil went up at least once a week and usually several times.

Since non-perishable goods such as CDs were likely to hang around in the shop for a while, it was easier to update the colour-coded chart than to change price-tags on every item.

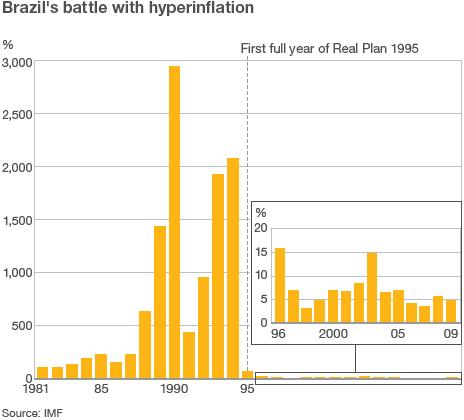

Brazil's inflation no longer runs at 2,000% to 3,000% a year, as it did during the worst of times.

But the memory of those rampant price rises is so scarred into the minds of those who lived through them that some of the era's coping mechanisms live on.

Busted banks

Of course, all this changed abruptly in July 1994 with an inflation-busting economic plan that included the introduction of Brazil's current currency, the real.

Looking at Brazil today, it is difficult to remember just what a game-changing moment that was. In many sectors of the economy, it transformed winners into losers and losers into winners.

The biggest losers were some of the country's most established banks at the time, which had learnt how to thrive in times of high inflation.

The best of them had responded with innovations, such as sophisticated data links to speed up cheque clearance across the whole of Brazil's vast territory.

Bradesco has continued to thrive since the end of hyperinflation

The worst were simply making a profit by holding on to the money a bit longer, delaying transfers so that the sum to be paid out was worth less than what had been paid in.

Those weaker banks were cruelly exposed once the easy returns from uncontrolled inflation dried up.

This led to a wave of bank failures, including the country's eighth-largest, Banco Economico, which had to be bailed out by the central bank in 1995 after it collapsed with debts of $3.6bn.

The sturdiest banks, such as Bradesco and Itau, have lived to see the 21st Century. On the other hand, they now have to contend with foreign rivals, such as HSBC and Santander, that entered the Brazilian market by taking over the weaklings.

New consumers

But while Brazil's banks were taking a hammering, the end of high inflation was a boon to those Brazilians who were too poor to have money saved in those institutions.

While prices were soaring, people at the bottom of the social scale simply had too little disposable income to be considered part of the consumer society.

Lower inflation meant beer for all in Brazil

When the economy stabilised, however, they acquired purchasing power for the first time - and suddenly, the new spending habits of the country's least fortunate citizens started to make an impact.

Sales of building materials went up, as the inhabitants of Brazilian favelas or shanty-towns upgraded their corrugated-iron and wooden shacks by replacing them with proper brick structures.

In 1995, Brazil manufactured a record 28 million tonnes of cement, more than half of which was bought by favela-dwellers.

And an entire class of people who had previously drowned their sorrows in the cheapest rot-gut cane spirit were able to switch to beer instead.

"Brazilians have certainly begun drinking more beer, because an enormous number of low-income consumers couldn't afford it before," advertising executive Flavio Nara of Brazil's DM9 agency told me two years after the Real Plan took effect.

As the man handling the account for Antarctica beer at the time, he was busy devising new ways of reaching out to these new consumers, whose importance has grown still further since then.

Continuity pays

The architect of the inflation-taming Real Plan, Finance Minister Fernando Henrique Cardoso, was rewarded by victory in the 1994 presidential election, followed by a second term in office four years later.

Those eight years under President Cardoso were not without their episodes of economic turmoil, notably the financial crisis of 1998-99 that led to a big devaluation.

But they provided Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva with a solid basis for his own two-term presidency - and it was Lula's decision to carry on with Mr Cardoso's economic policies, rather than changing course, that secured Brazil's current prosperity.

Now Lula's political heir, Dilma Rousseff, and Mr Cardoso's party colleague Jose Serra are getting ready to face each other in the second round of Brazil's latest presidential election on 31 October.

Either way, Brazil's economic policy seems set to continue on the same steady course, with both candidates committed to the successful Bolsa Familia welfare programme and wide-ranging infrastructure projects.

But if inflation had never been conquered, none of this would have been possible.

Lula himself is well aware of this. He has described the end of hyperinflation as "an extraordinary gain for salaried workers" and is proud of his achievement in combining growth with inflation control.

Faltering neighbours

Not all Brazil's neighbours have shown the same tenacity in trying to rein in galloping price rises.

Argentina had its own bout of hyperinflation in the late 1980s. Its solution was to link its currency, the peso, to the US dollar at a fixed one-to-one exchange rate.

Brazil has had the real since 1994 but the one-real coin came later

That solved the country's immediate problems, but meant that its monetary policy was in effect decided in Washington rather than Buenos Aires, leaving it vulnerable to the economic crash that finally came in 2001-2002.

More recently, Argentina's inflation has been creeping up again, but the perceived response of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner's government has been to play fast and loose with the statistics.

Leading economists, consumers' groups and even staff at the national statistics agency have accused the government of manipulating the inflation figures.

The country's official rate of inflation for 2009 was 6.3%, according to the International Monetary Fund, but forecasters polled by the Consensus Economics survey organisation estimate that the true rate was 15.4%.

If those figures are accurate, then the only Latin American country with a higher inflation rate is another of Brazil's neighbours, Venezuela.

Its consumer prices went up 28.6% last year and the rate has accelerated since then, putting a dent in the popularity of President Hugo Chavez's "Bolivarian revolution".

By contrast, Brazil's inflation in 2009 was a mere 4.9%. Unlike its fellow South American nations, it has embraced left-leaning politics while maintaining tough anti-inflationary discipline - an approach which its electorate looks set to endorse at the polls.