Maternity and paternity leave: the small print

- Published

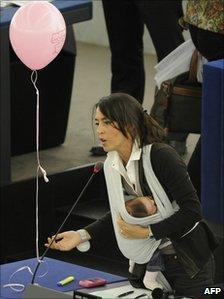

The EU draft law still has to get the backing of European governments

To think of maternity leave as a straightforward benefit to a new mum is wrong.

European policy makers need to balance not just their desire to provide security for mothers, and to ensure they do not damage their careers, but also how far to encourage gender equality by encouraging fathers to stay at home and, not least, the significant consequences for employers.

According to much of the research, there are some fundamental questions that politicians need to ask themselves before making a policy.

First of all, what is the real "replacement value" of the benefit? That means: how much do women actually get paid when they are out of work?

Often a headline figure of, say, 100% of salary, is misleading. Frequently there will be a "ceiling rate" to the benefit, meaning highly paid employees will not get their full salary.

In some cases percentage rates will decrease over time, or there will be a statutory base rate.

This, in turn, will affect the "take-up rate" of maternity leave. If a woman knows that she will be losing a significant amount of her income, she may be tempted back to work sooner rather than later.

Sustained leave can also affect pension rights and the long-term career prospects of a woman. If she sees she will be losing lots of money, or a promotion further down the line, again that may alter her decision on how much maternity leave to take up.

In some countries, certain employers offer significantly better benefits than those mandated by law.

There is also the issue - in some countries - of parental leave. This can be taken by either mother or father, or split between the two. This is usually paid at a lower rate than maternity leave but can last a lot longer.

And what of paternity leave? The European Parliament wants to force countries to offer two weeks' paternity leave at full pay.

Here are a few examples internationally of how these issues are handled:

Germany

Women get 14 weeks' paid maternity leave paid at 100% of salary (with no ceiling payments - so it could be very expensive). Some 2% of this is funded by health insurance but the rest is paid for by the employer. This is quite unusual and obviously places a heavy burden on businesses. The take-up rate is almost 100%. There is no mandatory paternity pay.

France

France has 16 weeks' paid maternity leave at 100% of salary (up to a ceiling). Mandatory paternity leave is 11 days but the employer will provide a few extra days on top. The take-up rate of the benefit amongst mothers is 99%.

New Zealand

New Zealand is interesting. Women receive 14 weeks' maternity leave at 100% of salary (up to a ceiling). But the woman does not need to be employed to receive this benefit. So economic protection at birth is considered a universal right. Because of its universal nature, take-up is around 100%.

UK

Minimum maternity leave in the EU is currently 14 weeks but could increase

Women get 52 weeks' maternity leave. Six weeks is paid at 90% of average salary. Weeks 7-39 are paid at a maximum of £124.88. Over the total period, women end up with average compensation of around 40% of salary. The take-up rate for the 39 weeks is 84%. There is two weeks' mandatory paternity leave in the UK, at a statutory rate.

Iceland

Iceland has one of the most interesting systems. Couples get nine months' paid leave at around 80% of salary. Three months is reserved for the mother, three months must be taken by the father and the couple can choose to share the remaining three. By 2007, dads were taking their full allocation of 13 weeks, the rest was being taken by the mother.

USA

The USA has 12 weeks' maternity leave mandated by federal law but there is no pay during this period. A number of states - including California, Rhode Island and Hawaii - have disability benefits that can be used by pregnant women. Only 42% of mothers in America access some form of paid maternity cover. This is low compared to other developed countries.

Data from the OECD Family database, external and the International Labour Organization, external