Crowdsourcing work: Labour on demand or digital sweatshop?

- Published

Crowdsourcing: Taking tasks traditionally performed by an employee or contractor, and outsourcing them through an "open call" to a large group of people (a crowd).

There are not many chief executives who can boast a workforce of half a million people around the globe.

But then Lukas Biewald's workforce is not your traditional one.

As boss of San Francisco-based CrowdFlower, he says that his company offers "labour on demand".

His employees are crowdsourced - people who work from home, when needed, on specific projects.

"It doesn't make sense to build a box around people, put in internet and plumbing and everything else, make them drive to work and have managers for them," Mr Biewald says.

"I think that companies like ours are really set to disrupt the whole outsourcing industry."

Lukas Biewald: "You can send work almost anywhere in the world at almost no transaction cost."

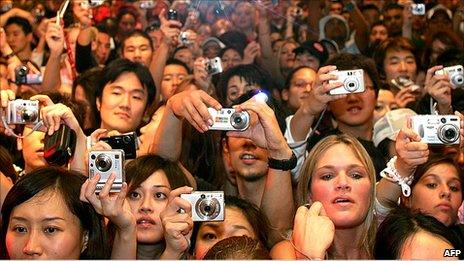

The rapid spread of broadband internet has allowed an explosion in companies offering a virtual workforce.

They provide people ready to complete jobs ranging from small data-driven tasks, to design, translation and content production - in fact anything really that can be done on a laptop with an internet connection at home.

Human intelligence

For companies using these services, the main benefits are cost and speed.

Workers are not employees, and are paid either an hourly or piece rate. In some cases work is done on spec, with only the "winner" pocketing the reward. And rates tend to be lower than would be paid to conventional freelancers.

So not surprisingly, the trend has attracted controversy, with some commentators comparing it to off-shore digital sweatshops.

The granddaddy of them all is Amazon's Mechanical Turk.

Its original purpose was to find duplicate web pages for Amazon products - a simple task, but one that computers were unable to do.

The company quickly saw that there was a wider application and the service went public in 2005.

It lists thousands of "human intelligence tasks", or HITs, from comparing different web pages, to transcription and tagging photos. The jobs pay anything from a few cents up to a few dollars for more complicated work.

And it didn't take long for the idea to be adopted elsewhere.

You can crowdsource web development from oDesk, find a writer to create your content from Elance, and source your logo for a few hundred dollars from Crowdspring or 99designs.

To fund your project there's Kickstarter, and if your customers get cranky you can send them to Get Satisfaction. When you're ready to move on to higher level research and development, you can put it out to the crowd at InnoCentive.

Virtual money

CrowdFlower compares its labour-on-demand model with cloud computing - when you divide a task between a group of computers it is accomplished more quickly, around the clock, thanks to greater processing power.

The company's workforce is available immediately, according to Mr Biewald.

"For example, you might have a directory of a million businesses and the job is to check that all the addresses are correct," he says. "We have people instantly around the world waiting for work to come through."

What makes CrowdFlower slightly different is that they don't source their workers directly from the internet.

Jobs are taken in, and then the company uses a diverse range of channels to fill the task. They work with initiatives allowing, for example, single mothers to work from home.

Traditionally games companies have offered players in applications such as Farmville the chance to take part in surveys, or watch adverts to earn in-game currency.

Now they have the chance to complete CrowdFlower tasks, through a system called Virtual Pay.

"I love it because we almost trick the game players into doing something useful for the world while playing these games. Just do ten minutes of real work that a real company can use, and we'll give you a virtual tractor. That way everyone wins."

'High quality'

A large part of CrowdFlower's effort goes into quality control. Mr Biewald estimates that about 99% of their research and development is focused on how to keep quality high.

They do this through a complex statistical analysis system where they track the accuracy of workers. As people progress up the food chain, they receive bonuses.

"The end result is that customers actually get higher quality data than they would have got through normal outsourcing," Mr Biewald says.

Clients past and present include Microsoft, PayPal, eBay and the US Department of State.

"When we started we weren't really sure if companies would buy it, but what we've seen is a lot of big companies are interested in this new model. In fact they're not just interested but they desperately want labour on demand."

Design for life

Operating from Australia and the US, 99designs launched in 2008 and crowdsources logos from a community of about 100,000 amateur and professional designers.

It uses a competition-style business model. The company looking for a logo offers a prize (the minimum is $200) and writes a brief. Designers submit logo designs, the customer reviews them and may ask for revisions, before picking a winner.

Copyright then passes to the customer and the winning designer is paid the prize money. The company charges a $39 listing fee, plus 15% of the prize fund.

99designs: "We're introducing customers to design that would never have done it before."

The company grew from the forums of Sitepoint.com, where according to founder Mark Harbottle, designers on the forums had started competing against each other in contests.

This then grew as entrepreneurs started offering cash for logo designs for their own companies.

"The designers loved it because it was what they were already doing, but they could get paid for it. We noticed it was happening and kind of latched onto the idea, and built software solution to help these designers doing what they were doing anyway."

The company estimates that a new design is uploaded to the site every five seconds. It pays out close to $700,000 a month to designers, and expects this to top $1m by the end of the year.

But can a crowdsourced design really compare to going to a traditional design agency? Mr Harbottle doesn't think there's a comparison.

"Would you get a better result from an agency? Probably but I think that what we do is that we serve that bottom part of the market.

"We're servicing the mom and pop shops, the small business, the freelancers and what these guys want is just an image to put on their business card or their website."

Brave new world?

As companies such as 99designs and their main competitor CrowdSpring flourish, the backlash has also grown.

Websites including Nospec.com and Specwatch have accused companies of exploiting designers and devaluing the profession. They say designers are producing work on a regular basis with no guarantee of payment, and claim that the payment on offer is far below market rate.

Screengrab of the Specwatch website. The members are anonymous

Specwatch, an anonymous collective, monitors design competitions, flagging up contests where, they claim, no award was made, and instances where the winning design was plagiarised.

Mr Harbottle says the community does effectively self-police, but that the company is doing what it can to stamp out intellectual property theft.

"If it was really bad we'd probably just ban them instantly. The thing that's important is to keep on top of the community to stamp out that behaviour, it's not acceptable, it's actually illegal."

The controversy goes beyond the design community.

When professional networking site LinkedIn started suggesting that people listed as translators might like to help with a crowdsourced project to translate sections of the site, external "because it's fun", the fallout from incensed professionals resulted in the setting up of a LinkedIn group protesting the move.

Education and experience is vital to ensure strategic design work, which also requires collaboration between client and agency, says Debbie Millman, president of the US association for professional design, the AIGA, which has around 20,000 members.

"Once you take that partnership away then what you're really asking for is work that is unstrategic, that is created in a silo of not having any real education about what the client is looking for, and not being able to collaborate on ideas or inspiration", says Ms Millman, who is also president of design company Sterling.

"I feel that when you crowdsource work, it's really not about collaboration of large groups, it's really about power, because you're taking away all the power of the designer to be compensated for their work, for their skill, and I don't see in anyway how that's collaborative. I think it's abusive."

Pro-spec commentators argue that the work benefits designers, by helping them build portfolios but Ms Millman is scathing about this.

"If somebody is looking to build their portfolio, perhaps they could offer their services pro-bono to an organisation that's really going to be able to help them. It's an imbalance of power.

"You wouldn't go into a restaurant and ask for five different meals and only pay for the one you like. Why should it be okay to work with designers that way?".

Offshoring the crowd

Given that crowdsourcing sites draw large amounts of workers from the developing world, critics see this as a new model for off-shoring jobs from developed countries.

"I think the criticisms are not crazy. It's something that we think about a lot," says CrowdFlower's Lukas Biewald.

"But I'd say most of what we see is not taking away jobs from people. It's actually getting extra work done that our customers wouldn't have been able to do otherwise."

The company has a partnership with a company called Samasource, providing work for people in Kenyan refugee camps, where the $2-an-hour rate of pay is far above what the workers could otherwise earn.

Mr Biewald believes the developing world has a right to benefit from new working opportunities.

"I don't see why someone in China should only be allowed to do the worst, most dangerous jobs we have to offer.

"The great thing about digital work is it's really hard to make a sweatshop out of digital work. It's really hard to force someone to do work, you can't beat someone up through a computer screen."

- Published17 October 2010

- Published14 October 2010

- Published7 October 2010

- Published29 September 2010