Irish political uncertainty dents markets

- Published

Protesters have marched on the Irish parliament building in Dublin

The euro and European shares, led by bank stocks, have fallen on political uncertainty in the Irish Republic.

The declines followed a call from the Green Party, the junior partner in the government, for a general election.

They were joined by opposition parties Fine Gael and the Labour Party, who demanded immediate elections.

The euro gave up early gains to dip to $1.36. Meanwhile banks were hard hit, with Lloyds, Royal Bank of Scotland and Santander all falling more than 4%.

Allied Irish Banks had fallen 3.9% by the close of trading, while Bank of Ireland was down 19%, more than giving up its gains from a meteoric rise on Friday in anticipation of the bail-out deal.

The UK's main FTSE index ended the day 0.9% lower.

Share prices and the euro had earlier risen after Sunday's announcement that Dublin would get a large bail-out.

The yields on 10-year Irish government bonds - a measure of how much interest markets would charge to lend for this period of time - ended the day almost unchanged at 8.1%, despite having fallen to 7.9% during the more optimistic trading in the morning.

Political 'certainty'

The Green Party's decision comes as the government begins the formal process of applying for up to 90bn euros (£77bn; $124bn) of European Union-led loans agreed on Sunday.

The Green Party's leader, John Gormley, said: "We have now reached a point where the Irish people need political certainty to take them beyond the coming two months.

"So, we believe it is time to fix a date for a general election in the second half of January 2011."

However, Paul Mackel, HSBC currency strategist, said the political developments in Dublin "had taken some optimism" out of the rescue plan news.

Meanwhile, two independent members of parliament upon whom the government depends for support said that they would not commit to vote in favour of the budget due before the end of this year.

UK contribution

The total level of the UK contribution is expected to to be about £7bn.

This includes contributions to European Union and International Monetary Fund (IMF) bail-out schemes, and direct bilateral loans.

The exact amount that Irish Republic will borrow will depend on the IMF's analysis of Dublin's needs over the coming days. The IMF is expected to provide about a third of the financing.

Chancellor George Osborne told BBC Radio 4's Today programme that it was in the UK's national interest to help the Irish Republic.

"Our two economies are connected, and our two banking systems are interconnected.

"Ireland is a friend in need, and we are here to help."

Defending the move later in parliament, Mr Osborne said "this is a loan and we can expect to be repaid".

He also ruled out the UK ever becoming part of a permanent bail-out mechanism for the eurozone proposed by other European governments.

Smaller banks

The crisis in the Irish Republic has been brought on by the recession and the almost total collapse of the country's banks, analysts say.

Ireland was once known as the Celtic Tiger for its strong economic growth, helped by low corporate tax rates, but a property bubble has burst, leaving the country's banks with huge liabilities and pushing up the cost of borrowing for them and the government.

The EU and IMF loans will be provided to the Republic over a three-year period.

"It is necessary to help Ireland, otherwise the whole eurozone would be in danger," said Austrian Finance Minister Josef Proell.

Under the bail-out deal, Irish income tax is set to increase, but the government has said that the country's low 12.5% corporation tax was "non-negotiable".

Irish Finance Minister Brian Lenihan said the bail-out would also help to reduce the government's budget deficit to a target of 3% of GDP by 2014.

To help achieve this, the Irish government will publish a four-year budget plan on Wednesday, which is due to announce 15bn euro of austerity measures, including 6bn euros next year.

Mr Lenihan said EU and IMF officials had seen the outline of the budget plan, and "it is unlikely that they will request changes".

Marie Sherlock, economist at the Irish Republic's biggest union, Siptu, said the composition of the budget will be "of crucial importance".

She added: "We need an awful lot more in terms of spreading the burden of the pain, the burden of adjustment, between those who can shoulder it, and the vulnerable who have been very much targeted to date."

Dublin will also use the budget plan to outline how the country's banking industry will be restructured, with Irish banks expected to be turned into much smaller institutions.

Despite the bail-out announcement, and the Irish government's efforts to put in place austerity measures, credit rating agency Moody's has warned that it is "likely" to have to reduce its rating for the country.

However, Moody's added that despite the "multi-notch downgrade" it would still leave the Irish Republic with an investment-grade rating.

Portugal concerns

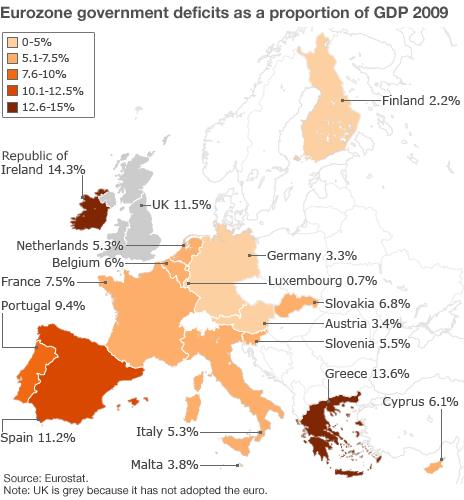

Some EU officials fear the Republic's financial problems might spread to other eurozone countries with large budget deficits, particularly Portugal.

BBC business editor Robert Peston said "it would be a very foolish individual" who predicted that the Irish bail-out was "the solution to all of the eurozone's problems".

He added: "The reality is that Portugal also has excessive debt, although not to the same scale as Ireland.

"But Portugal also has real structural problems that they will struggle to get through on their own."

Our business editor added that the EU still had sufficient funds to bail-out Portugal, but that it would then leave other nations such as Spain and Italy to "muddle through on their own".

Portugal's Finance Minister Fernando Teixeira dos Santos said the aid package for the Irish Republic "reduces uncertainty and reinforces market confidence" in the wider eurozone economy.