Playbutton: Self-playing music for digital times

- Published

The Playbutton is a music album that plays itself

If you still buy music on CDs or vinyl from record shops, you have to take it home before you can hear it, unless you carry a portable player around. But what if the record could play itself?

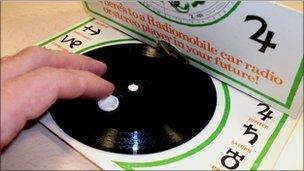

The idea is not as weird as it sounds. Back in the 1970s, some promotional flexidiscs - records pressed on extremely thin plastic - actually came with a primitive cardboard gramophone attached.

All you had to do was place the steel pin "stylus" on the edge of the record and rotate the disc with your finger to hear the sound encoded in the grooves.

Now, nearly 40 years later, someone has come up with another sound carrier that has the playing equipment built in.

And, quirky as it seems, the result could help make physical music formats cool again in the digital era.

The Playbutton is a digital music album in the form of a badge, providing album artwork that you can wear. Pin it to your lapel, plug in a pair of headphones and you can walk down the street displaying your musical taste as you listen.

"It's a small object, perfect and immediate, that you can hold in your hand," says Nick Dangerfield, founder of the New York-based Playbutton company.

Support for artists

Mr Dangerfield says he came up with the format in response to a widespread feeling that people were "tired with CDs", but finding digital music downloads "not entirely satisfying".

"I thought about giving a new use to digital files by putting them in a dedicated player. It's an iconic form that gives you the chance to show your affiliation," he says.

The self-playing record was invented in the 1970s

"It shows that you've purchased the music, so it shows your support for the band."

Playbutton is a small company, with a mixture of full-time and part-time staff. As well as having four people in New York, it has two in Tokyo, two in Barcelona and one in London.

Eight initial releases are scheduled to come out following the official launch of Playbutton in February 2011.

The artists are all little-known at present, so the launch will be publicising new and cult bands as well as a new music format.

The most established is German glitch-techno group Oval, who have been releasing albums on obscure independent labels since 1993.

Others include several New York-based acts including self-proclaimed "indietronica" band Javelin, who are signed to David Byrne's Luaka Bop label.

Price is right?

So where will Playbuttons be going on sale? And most importantly, how much will they cost?

Clearly the world's remaining record shops are a potential outlet for the new format. Mr Dangerfield says he has had talks with London's Rough Trade record shops to make Playbuttons available in the UK.

Nick Dangerfield says he does not expect the Playbutton to replace CDs

But he also hopes that Playbuttons will be an opportunity for artists and labels to get recorded music into shops that do not currently sell CDs or vinyl - "to get a physical presence back in retail".

Another obvious way to market them would be on merchandise stalls at concerts. Mr Dangerfield thinks the ideal price would be $15 (£10) if bands sold them at their gigs, but the price could be up to double that, "depending on the type of release and sales channel".

"It's up to the artist to decide how much they want to charge," he says.

Isn't that pricing the Playbutton too high? Mr Dangerfield thinks not.

"If you say to people, 'It's an MP3 player and it's $25,' they say it's cheap," he says. "But if you say, 'It's an MP3 player and it's already got a good record inside,' they think it's expensive."

From another time?

Like most electronic gadgets these days, Playbuttons are Chinese-made, with all production sourced from a factory in Shenzhen.

"It's good that technology has got to the point that something like this has become viable," says Mr Dangerfield.

But in some ways, the technology used in Playbutton is "anachronistic", as its inventor admits.

The Playbutton has a simple set of controls

The 256MB memory card inside the device has long been superseded by larger sizes for most other uses, but is just right for the Playbutton, since it holds only one album.

Powered by a rechargeable lithium battery, it has play, pause, skip and volume controls on the back, but there is no shuffle play.

Mr Dangerfield thinks the sequencing of an album is about "surrendering control to the artist" and that something important is lost when we have the power to rearrange its track listing.

"Sometimes it's better just as it comes," he says.

For these and other reasons, he does not expect the Playbutton to replace the CD.

But he does hope that his creation will inspire people to rediscover the joy of physical music formats, by giving Playbuttons to others as presents and even swapping them to spread the word about a favourite band.

"It's like the cover of a book you're reading," he says, "it's displaying music that you like."