Coal-to-gas power shift 'to cut energy costs'

- Published

Natural gas is less dirty than coal, but not clean enough according to critics

Switching from coal to gas power could save European nations 450bn euros ($596bn; £377bn) in the next two decades and cut carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, a group of gas firms says.

European coal-fired power stations emit 70% more CO2 than modern gas plants, the European Gas Advocacy Forum said.

Gradually replacing coal power stations with gas could help Europe cut CO2 emissions by 80% by 2050, it said.

But sceptics say renewable energy rather than gas is the way forward.

Quick and easy

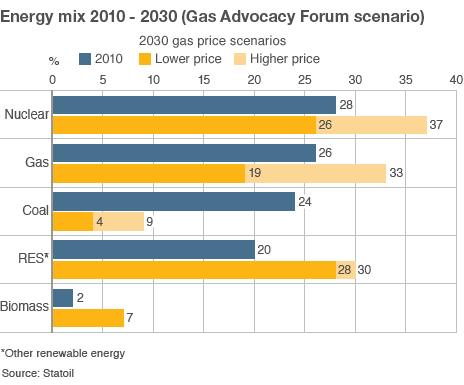

The European Gas Advocacy Forum, which is made up of eight gas companies - Centrica, ENI, E.On Ruhrgas, Gazprom Export, GDF Suez, Qatar Petroleum, Royal Dutch Shell and Statoil - would like to see coal's share of the energy mix fall from 24% currently to between 4% and 9% by 2030.

During this period, power stations using gas, biomass, other renewable energy sources and nuclear energy would produce more to fill the void, the group said in a joint position paper presented to the European Commission on Friday.

The gas companies insist gas should fill most of the void during the initial two decades as this would be the quickest and cheapest solution.

"The reason why it is cheap is that gas power requires lower investments than coal and nuclear power plants," the head of Statoil's gas division, Rune Bjornson, told BBC News.

"It offers a shorter lead time and there are no technological challenges."

During the following two decades, the role played by gas should gradually give way to more rapid growth of nuclear and renewable energy, mainly wind power, Mr Bjornson said. Gas would work well as a backup for wind power, he added.

Moreover, during this period, he expected carbon capture and storage technology to become cost-effective, thus helping to reduce or eliminate emissions from gas power stations.

'Not zero carbon'

But some remain sceptical about the gas industry's economic, technical or environmental arguments.

"There is potentially a very important role for gas, plus carbon storage, which can be regarded as low-carbon," David Kennedy, chief executive of the UK's Committee on Climate Change, acknowledged.

However, "that technology is uncertain," he told BBC News.

"Although gas is less carbon-intensive than coal, it is not zero-carbon or even low-carbon," Mr Kennedy said.

"You cannot decarbonise radically using gas and we shouldn't set off down that path."

Energy security

Another reason why many are sceptical to increasing the use of gas relates to the security of supply.

Such concerns are largely based on a perception that Europe could become dependent on supplies from Russia's Gazprom in particular, a scenario widely deemed undesirable following its rows with Ukraine in recent years.

Such concerns are overdone, said Mr Bjornson, insisting that global estimates point to more than 250 years of economically recoverable natural gas resources at current consumption levels.

"Availability of gas and the number of supply sources have never been better than they are today," he said.

Dr Robert Gross, director at the Centre for Energy Policy and Technology, accepts that.

"There is more of it than we thought there was," he told BBC News. "We currently have a surplus of energy globally, because the Americans built a load of energy capacity and then found all this shale gas."

He added, "Need we really be as fearful of reliance on countries that we feel nervous about?"

Price issues

But perhaps the biggest obstacles to a consensus in this debate relate to distorted prices.

The gas industry objects to subsidies or a failure to price in the impact of other power sources, insisting governments should avoid picking winning technologies and instead leave that to free-market mechanisms.

But others argue that bilateral long-term gas contracts, along with other market and regulatory issues, mean gas prices are too closely linked to oil prices.

"The fact lots of gas is available doesn't mean that markets will deliver it at an affordable price," warns Dr Gross.

Fears that gas prices could rise in line with oil prices, in spite of an ample supply, are real and thus a concern for many, according to industry observers.