Field of dreams: Can small festivals bring riches?

- Published

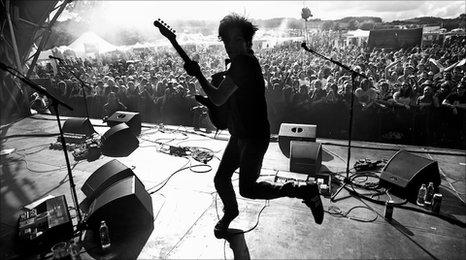

Fewer bands, fewer stages, fewer fans, plenty of fun. But not always plenty of profit

In June, Ralph Broadbent will complete his final university exams.

And like many fellow students, he knows that after all the revision and preparation, there is, at least, a summer music festival awaiting him.

But rather than being one of the hundreds of thousands of people who merely attend such UK events, Mr Broadbent, at the age of 23, is running his own.

The UK festival market is dominated by big promoters: Live Nation (Download, Wireless, and a stake in Glastonbury), Festival Republic (Leeds, Reading, Latitude, Electric Picnic) and DF Concerts (T In The Park, Oxegen).

These operations, with teams of full-time staff, massive marketing budgets and a healthy swathe of corporate backing, have helped make the UK the capital of the festival world, with fans spending an estimated £275m a year.

But beneath such high-profile events are many more (between 400 and 900, depending how a festival is defined) which will cater for a few thousand, or even just few hundred, people.

'We lost thousands'

Mr Broadbent's Y-Not Festival began life five years ago, when 200 people gathered at a quarry after his parents scuppered plans for a secret party at his house by announcing they were no longer going away on holiday.

Now planning its sixth year, in the heart of the Peak District, he is looking ahead and hoping to sell about 5,000 tickets in 2011.

However, while he hopes to make a living from the festival after university, the civil engineering student knows that for small event promoters, it is not an easy career.

"We lost thousands," says Mr Broadbent, looking back on the 2009 event, which was preceded by three weeks of heavy rain and then a hailstorm on the day before festival-goers arrived.

"We could have cancelled and there was insurance that would have covered cancellations," he says.

"But we had 4,000 people coming and they wanted to come, the bands wanted to come.

"Everyone had an excellent time, but financially it was a disaster," he adds.

"I knew that the next year, I would have to make a fair bit of money just to break even over the two festivals. That's quite hard when your friends have made a few grand, just by working part-time at Sainsbury's during the summer holidays."

Campfire plan

Many promoters insist that their event is first and foremost about creativity, and that profit, when it comes, is a welcome by-product. And certainly not all events make money.

Festival organisers have to jump through hoops to satisfy licensing authorities

Soaring costs or changing economic circumstances can force events to be scrapped. In 2010, for example, the Glade festival was axed - with its rising police bill partly blamed. The Big Green Gathering met a similar fate in 2009.

And when a successful small event hits financial trouble, its survival can come at a heavy price - the loss of independence - as happened with Festival Republic's purchase of The Big Chill.

But for Andy Rea, the 2000 Trees festival that he runs with five friends is not about making money.

Rather than a business venture, it is more of a personal project for its founders, who became disillusioned after years of attending larger festivals and wanted something a little more personal, environmentally sound and ethical.

"We were sitting around a campfire at a festival we'd been going to for a few years and maybe we were just getting old, but we weren't finding it as fun any more," says Mr Rea.

"The music was increasingly mainstream, the prices were going up and up, and we felt that we were being taken a bit for granted, that the organisers were mainly about profit.

"And then we started thinking about how we'd make it better."

Budgets and bouncers

That same group of six are now preparing for the fifth year of 2000 Trees - and are on a high after the event was named Best Grassroots Festival at the UK Festival Awards (as well as a far from bog-standard second place in the best toilets category).

And with none of the organisers - who include an accountant, a lawyer and a PR executive - able to work full-time on the festival, they have been learning along the way.

Mr Rea says he uses only a week of his annual leave every year for the festival ("my girlfriend wouldn't like it if I took more") though he admits it can take over in the months leading up to the event, held in a farmer's field near Cheltenham.

"Afterwards I tend to have a couple of days to sleep it off, then it's back to the day job," he adds.

And while breaking even is the goal, avoiding making a loss is important, which can be tricky when tickets cost £50.

This is less than a third of the price of many festivals, although it lasts two rather than three days and the headline acts, while established (2010 featured Metronomy, The Subways and Bombay Bicycle Club), are at the more affordable end of artists.

"We do keep a very close eye on the budget," says Mr Rea.

"In our first year, we even all trained as bouncers, so we could cut the number of security guards we needed to hire - although as we've got bigger, we've had to pay a company to do this for us.

"And one of the lads has a licence to run the bar. I think he fancies having a pub one day."

It is an approach admired by Fiona Stewart, founder of the Green Man festival, which began on a small scale but now hosts 15,000 people.

"Remember, every time you pay someone to do something you can learn to do yourself, that's a loss to your festival," she says, adding that building good relationships with contractors can also help to keep costs lower.

Being willing to fight your corner against the restrictions imposed by local councils, or to challenge the level of policing you are told an event needs, can make the difference between whether an event is viable or not, Ms Stewart says.

Exclusivity deals

Festival fans may face paying a little more for tickets this year

Securing bands who are both affordable, but who also have enough of a reputation to drive ticket sales, is "probably the biggest problem festivals like ours face", says Mr Rea of 2000 Trees.

"We started off just going for bands we liked. Only this year we started booking clusters of bands who have fans in common - with the idea of making the ticket more appealing."

The demand for acts is partly because there are so many events in a concentrated period, but also because some performers sign exclusivity deals which allow them to play at at just one or two festivals (as seen, for example with the Libertines at Reading and Leeds in 2010).

"Of the five groups topping our wish list, four of them are either on exclusivity deals or committed to playing international festivals," says Y-Not's Mr Broadbent, whose events puts the emphasis on what he describes as "up-and-coming, cutting edge" bands.

In the past couple of years, he has managed to sign artists well who, by the time they come to perform in the summer, have had some success and so can be moved higher up the bill.

"And if we booked them in February, then we pay what we agreed in February, so in those cases, you do get a bargain," he says. "Though we are still paying a bit of a premium on the chance that they will become a hit."

This clamour for acts, plus the looming rise in VAT, means the price of tickets to his event, which were £55 in 2010, are set to rise, perhaps by £10 or almost 20%.

"We're finding the costs to hire the same bands are sky-rocketing," he says.

Spotting an up-and-coming band is a way to fill your bill on the cheap, Mr Broadbent says

At a time of rising unemployment, Mr Broadbent knows that he is both graduating at a time of economic uncertainty and running a festival in a period where many are more reluctant to part with diminishing disposable income.

But he still feels the future is bright for his business.

"We've got a low-cost alternative to the major festivals - not just your ticket outlay, but the food and drink, and T-shirts are usually a bit cheaper too, and as most of our customers live quite close by, the transport costs tend to be lower too," he says.

"So yes, it's been tough, but the recession has perhaps been quite kind to the likes of us."

- Published18 November 2010

- Published14 June 2010

- Published8 June 2010

- Published20 May 2010