Remember the "Green economy"?

- Published

Solar panel economics has changed as mass production has made them more affordable, though subsidies have also been cut

When the global bank HSBC came to name its latest report on the green economy, "Glimmer amid the gloom" was its optimistic choice.

In the midst of a worldwide recession, 2010 kicked off with a global failure to reach a deal on measures to tackle climate change.

By the year's end, hopes were so low that a limited and non-binding agreement at a follow up conference was almost universally praised.

Yet HSBC may be right to identify a glimmer behind the headline failures.

The bad

Investment in clean energy and low carbon technology was hit twice over.

The economic downturn reduced the amount of money available, and huge uncertainty over the rules meant people did not want to invest what was left.

In Europe, cash strapped governments went back on promised subsidies. Spanish solar subsidies in particular were heavily cut.

"That had massive shockwaves," according to James Vaccaro, head of investment banking at European ethical bank Triodus.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the failure of the 2009 Copenhagen conference to generate investment will increase the cost of limiting climate change to 2 degrees Celsius by about $1 trillion (£640bn).

The election in the UK led to further uncertainty.

Despite new measures, since then accountants Ernst and Young estimate there is now a funding gap between planned investment and what is needed to meet government targets of around £330bn ($516bn).

The 2010 Cancun conference promised $100bn globally, with no word on where it was to come from.

Small steps

"The big, exciting stuff that was going to come out of a very successful [global conference] didn't happen, but you have steady growth in a number of technology areas", says a philosophical Ben Sykes, director of innovation at the UK's Carbon Trust.

The recession, he says, has driven larger firms to look at energy efficiency in unlikely areas. The trust is currently working on a new way to freeze dry Jelly Babies.

For Alan Thompson, consulting engineers' Arup's UK director of energy, it is a move away from "green bling" to things that can be commoditised and rolled on scale by well known firms from other sectors.

His firm is working on a way of reducing the cost of offshore wind through new floatable foundations and new ways of quickly calculating the viability of wind farms.

It is a view shared by some investors.

"The learning curve has accelerated during the crisis, particularly in solar," says Nick Robins, head of HSBC's climate change centre of excellence.

Cheap solar

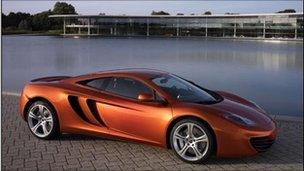

Lighter cars also help cut emissions

In the UK, solar is the boom area of the green economy.

The government's feed-in tariff has prompted more than 10,000 new solar panels to be installed so far with expectations of far more in the future.

In Europe, generous subsidies are being withdrawn, causing problems for installers. But at the same time, the economics of the panels have changed completely thanks to scale.

"The cost has halved in the last 18 months," says Andrew Lee, head of sales at Sharp Solar UK. The company is the largest UK manufacturer and plans to create new jobs this year.

Most panels, of course, are made in China, which is now the leading producer of solar photovoltaic cells.

Thanks to large new factories in china, "grid costs are now equivalent to nuclear in the US" - and falling, according to Anthony Froggatt, an energy expert at think tank Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs.

Efficient cars

Electric cars were perhaps the most glamorous hope of the green economy.

Econogo makes electric scooters The firm won awards and plenty of coverage.

But the firm's director, James South, says buyers were not as keen as the press.

"We found that it was still a novelty, a gadget," he says.

The company has closed its shop and is now looking instead at fleet sales.

"This year will be a litmus test for the electric car," says Richard Bremner, from the website Clean Green Cars, who worries about range and cost.

But 2010 has already seen big developments in petrol and diesel car efficiency.

"The car industry has taken a really big hit, but they have proceeded more or less unabated with their plans," towards lower carbon vehicles, says Mr Bremner.

Even F1 manufacturer Mclaren says it is pioneering a new type of carbon fibre chassis in its latest sports cars - it says has reduced the cost of that type of light weight build by 90%.

The cost has gone down so far that BMW, under pressure to reduce emissions, plan to release a car made entirely from carbon fibre - dubbed the Megacity.

Green china?

For the Chinese government, reducing vehicle fuel consumption is pressing.

The shift from bicycles to cars created a big pollution problem in China

"China knows it has an issue with energy security, in particular oil," says Mr Froggatt.

Indeed, China has seen the strongest increase in investment in clean technology worldwide and is already a leader in solar and wind technology.

Nick Robins from HSBC says that electric cars and other low carbon technologies are next. The government wants these "high value" sectors to account for about 15% of economic output, or GDP, by 2020.

The message is filtering down, according to Ann Wang, a young entrepreneur in China who is on the board of the China Youth Climate Action Network.

"All of a sudden you see green signs everywhere," she says.

"Every car is trying to say 'we're eco-friendly, environmental'. You really feel this big change."

A survey by a social networking site P1 found most of its wealthy members wanted safer, "more natural" beauty products, for example.

Other "green lifestyle" businesses, such as those selling organic vegetable boxes, have also sprung up in Shanghai.

But despite this, Ms Wang worries many do not yet understand the details of reducing emissions.

Oil fears

China is not the only country worrying about oil.

The price ended the year well above IEA forecasts, close to levels seen before the crash.

Anthony Froggatt admits that so far higher oil prices have not prompted an increase in actual investment - outside china - but he argues the transition away from oil will have to happen.

"The question is how much society is prepared and has started to put in place the infrastructure, prior to significantly higher price signals", he says, from ever rising oil prices.

But a switch away from oil need not mean reduced emissions.

In the US, apparently plentiful shale gas may well replace oil, only reducing emissions slightly. In China, clean electric cars may continue to be powered by plentiful Chinese coal.