Coal confirms its lead as king of fuels

- Published

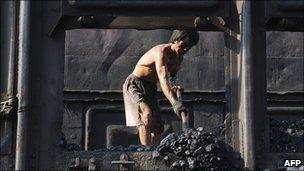

China is already the biggest producer of coal and home demand continues to grow

Generations ago the black stuff hewn out of the earth was called King Coal.

It powered the Industrial Revolution centuries before anyone began to think about climate change and fossil fuels fell into disrepute.

But now, in the 21st century, coal is rearing its head as king once more.

Growing demand for it in Asia has created a new boom, which is welcome news for producers such as Australia, Indonesia and Russia.

Energy companies across the world are vying with each other to snap up new sources.

"The consumption of coal is growing at a massive rate at the moment, particularly in Asia," says David Price, director of Cambridge Energy Research Associates

Growing demand

The Chinese and the Indians are pushing their consumption up very rapidly and production levels are now approaching five billion tonnes a year, which compares with about three billion tonnes at the beginning of the millennium.

The increase in China and India is a simple case of raising living standards. These countries are still classified as developing countries.

"In India, half the population still has no access to electricity and government policy is firmly fixed on ensuring that they are connected to the grid at some stage in the next 10-20 years," Mr Price says.

"Coal is the cheapest available and the most available fuel which will enable that."

Increased production

There are two types of coal, explains John Wallington, chief executive of Coal Africa.

coking coal, or metallurgical coal, which goes into steel making

thermal coal, which is basically used for everything else, especially for raising heat for power generation.

Mr Wallington's South African company produces both and demand is growing.

"The demand influences world prices for coal, although prices are not as high as they were in 2008 when everything peaked before the financial crash," he says.

"The Chinese are becoming the mainstay of the market - they import a huge amount as well as produce a huge amount, so they are effectively driving the world market."

Russia is the third biggest coal exporter. It has huge reserves of high quality coal, particularly in Siberia, which produced 300 million tonnes last year.

They are focussing not only on Asian markets, but also on rising domestic demand and it is a policy of the Energy and Mines ministry in Moscow to increase the amount of coal being used.

There is continued opposition against the use of fossil fuels because of pollution and global warming

New mines are opening all the time, particularly in Indonesia which is one of the most rapidly developing coal producing countries in the world.

Australia and most other areas in the world are also trying to raise production.

Pollution fears

An increase in production is the opposite of what the global climate change forums have wanted to see because coal is one of the dirtiest fuels when it comes to harmful emissions that most scientists agree causes global warming.

Critics question whether there is the will among coal producers to make their technology cleaner, so it emits less carbon dioxide.

"There is no doubt coal is one of the dirtiest fuels in terms of CO2, but it is only one of three fossil fuels," Mr Wallington says.

"Natural gas and oil also emit carbon, and they also need to decarbonise to reach current plans for 2050," he asserts.

He understands that coal is going in a direction that policy makers would prefer it not to go.

"We have this conflict between the requirements of the developing world for increasing citizens prosperity, and the demands of the global environment," he says.

"I am not sure how you square that argument, but I think the answer is probably to find ways of decarbonising all fossil fuels."

Monetary concerns

The technology for decarbonisation that seems to be lining up as favourites at the moment are forms of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) - to capture the CO2 emissions either before or after they have been generated, and then to lock them away underground.

But on a large scale, that technology is extremely expensive.

The technology does work. It has been applied all around the world. The only thing that still needs to be proved is whether or not the scale needed will be commercially viable.

"That is close to being shown," Mr Wallington says.

"If you look at all the alternatives to the current operations, renewables or CCS or nuclear or whatever, you are looking at substantial increases in the price of electricity to pay for it."

With the Chinese building up their own production and likely to be exporting to the rest of the world in the next 20-30 years, it is quite probable that it will be them that develop CCS.

Mr Wallington points out inconsistencies in the way the US and Canada, which are limiting the construction of coal powered facilities themselves, remain happy to export coal to China.

Political moves

Mr Wallington would like to see a rapid rise in new technology.

"The new thermal plants being built are certainly more efficient than older ones," he says.

"And of course, we already have the technology to have emission-free power plants - the only constraint is the cost."

Various governments around the world are considering the introduction of climate change legislation.

"It will have an impact on all businesses," Mr Wallington says.

"It is interesting that people think that the cost of clean coal technology is too high, yet when you look at the alternatives to coal, they are even higher than that - for example, nuclear, solar, wind.

"None of them are really viable right now for bulk power supply without massive subsidies."

The real costs of all these alternatives are still to be determined, but there is no doubt that clean coal technology can double the cost of coal in producing energy.

"If tax becomes an incentive to improve your energy efficiency, then it could work," Mr Wallington says.

- Published6 January 2011

- Published7 October 2010