Social entrepreneurs: Making money for the common good?

- Published

One Water is one example of social entrepreneurs at work

Making and giving money are generally considered to be two separate operations.

First you make your cash. Then, if you're of a philanthropic bent, you give some of it, maybe a lot of it, away.

But how about combining the two, taking the entrepreneurial spirit and harnessing it to do good?

One Water was an idea dreamt up by a bunch of friends in a pub, with the aim of creating a business that sold bottled water and gave away all its profits to water projects in Africa.

Duncan Goose, whose background is in advertising, is managing director.

He explained: "Actually there is not very much you can do to market water in a bottle. It's water, it's in a bottle. You can change the cap, alter the label, but not much else.

"But if you make the aim of the business a project like providing water for people in Africa, then you can use that to sell the bottle."

And it works. It competes head to head with Evian and Perrier, while the profits primarily go towards PlayPumps.

This is an ingenious concept that hitches up a playground roundabout to a pump and a borehole and uses children playing on it to pump water up to a storage tank.

Branching out

One Water claims to have helped a million people in Africa get safe clean drinking water.

Now it's branching out into One Vitamin Enhanced Water, One Condoms, One Toilet Tissue and One Handwash, as well as African microfinance projects.

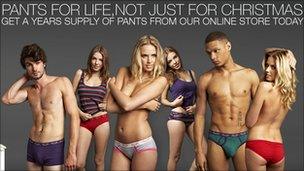

There are other similar stories. Pants To Poverty is an ethical underwear brand championing environmentally friendly clothing production to support Indian cotton farmers.

Bikeworks, in the heart of London's economically deprived East End, takes on the homeless and long-term jobless and teaches them to service and sell bicycles.

It's hard to measure the number of social entrepreneurs, but in the UK, social enterprises legally categorised as Community Interest Companies number almost 4,500.

But there are many more that would call themselves social enterprises, with a vast range of structures.

Some are tightly run businesses which, after costs, push all profits into their own charitable operations.

Others make money from running community projects, often for local authorities. Others have charitable sidelines and yet more are charities that have simply become more business-minded.

For instance, the UK charity Mencap, which campaigns for people with learning difficulties, gets only 10% of its resources from fund-raising. Much of the rest has to come from commercial operations.

Blurring the divide

For some, this confusion is a problem. Professor Aneel Karnani from the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, says there should be a clear split between a real business and a philanthropic organisation.

"Companies should do well, citizens should do good," he says. "I think it's good to separate profit and not-for-profit organisations.

Pants To Poverty have an eye-catching way of supporting Indian farmers

"Having this middle ground isn't useful. It opens up questions of governance: who is going to have the final say, the investor, the manager or the donor?"

Also, if you cannot categorise and define a social enterprise, it's hard for government to help them or in any way regulate them. What targets do they have to reach if, for instance, they are to receive tax incentives?

And yet social enterprises continue to attract not just the young and idealistic, but seasoned investors.

HCT, which runs bus operations in Hackney and Yorkshire in the UK, ploughs some 30% of its profits into community transport projects for the elderly and disabled.

It found itself growing at some 20% a year, but a year ago it needed capital to buy a new fleet of buses. It simply could not offer the kind of return conventional investors demanded.

Managing director Dai Powell found a "social loan" instead. "The investor gets a social return as well as a financial return," he says.

"We set an annual target with the investors, as regards what we hope to achieve in terms of social impact, and that is monitored with quarterly presentations.

"If we don't meet the social targets, we can, in theory, default on the loan."

Investment or subsidy?

The loan came from venture capital group Bridges Community Ventures. Its executive director, Antony Ross, has an orthodox background in venture capital, an industry that demands high returns, as well as fast growth for its investors.

But when he helped set up Bridges, he was selling those investors something very different, as he explains.

"Investors are very attracted by the idea that they can put their money into a social enterprise, the enterprise can grow and with its growth you have the resources to repay those funds - and then those investors can use those funds to support another social enterprise."

The potential investors here are often high-net-worth business people with an eye to philanthropy, and treating it as a business is very appealing. However, Prof Karnani thinks the blending of the two is misleading.

"What we are really talking about here are enterprises that don't earn the full return that a competitive market requires, so they get subsidised capital in some form," he says.

"The investors are willing to take a lower return. That's equivalent to saying the investor is making a donation to that business.

"Rather than mixing the two, the bus company could run as a profit-making company, the shareholder [could] get a proper return and then decide to put the money into a community project. I don't see why the two should be confused."

And yet social entrepreneurs show no sign of being confused themselves, while their ranks appear to be swelling - however you define them.

Most would argue that definition is not a problem, so long as they can, in some way, make a good living for themselves - and a better life for others.

- Published19 December 2010