For economic inspiration, look to space

- Published

"Let us look heavenward and change the game," Mr Tetlow says

In the same week as we discovered that UK growth rates are significantly worse than expected, a small company based in Guildford announced plans to put a mobile-phone powered satellite into orbit.

Set against the challenge of not just re-balancing, but re-building our economy, sending a phone into space seems like a piece of technological whimsy.

It could, however, be interpreted as something rather more important: a sign that if we are seeking economic inspiration, we could do worse than look to the skies.

The one ray of light amidst the gloom of the latest growth figures was the robustness of the UK's manufacturing sector.

Space invaders

Accounting for some 12% of all economic output, it has been growing at its fastest rate for 16 years.

We are not about to return to an age when Britain was the workshop of the world, of course.

But there are future-friendly industries where we can and do lead. Chief amongst these is space.

Over the past decade, our domestic space business, which is focussed mainly on telecommunications satellites, has grown at about 10% per year. In other words, at the same rate as China.

With global demand for information and connectivity growing rapidly, its not hard to see a buoyant future for this sector.

However, the ambition of our space sector goes much further, and here there may be inspiration and opportunities for other parts of UK Plc.

Jet-rocket engine

Skylon is a UK designed space-plane that could signal the greatest step-change in aviation since Sir Frank Whittle created the jet.

At its heart is a jet-rocket engine - Sabre - and an incredible heat management system that would not only allow us to "re-invent" air and space craft, its technology could, amongst many other applications, also make current jet engines 20-30% more fuel efficient.

The product of decades of research, the idea for Skylon should have died with the end of the Horizontal Take-Off and Landing, or Hotol, project.

The dogged determination of a small team of scientists and engineers, who refused to let go of a dream when funding and favour were in short supply, kept the idea alive. We may all benefit from their belief.

The key element, which will be tested this summer at Culham, Oxfordshire, is the engine's heat exchanger.

At high speed, the air entering the Sabre unit will hold a temperature of more than 1,000C.

This is far too hot to burn the Skylon's hydrogen fuel efficiently and could even melt the engine's innards, so the air must be cooled to -140 oC in just a few milliseconds.

Formidable as this challenge is, the engineers at Reaction Engines, the team behind Skylon, reckon they have cracked it.

The benefits are potentially huge.

In a world dependent on space, launching satellites is a growing business.

It is also hugely expensive: lofting a typical communications satellite currently costs some $250-$500m.

US entrepreneurs, encouraged by their government, are racing to deliver launches for less.

There will be, therefore, a lucrative market for a more cost effective, single-stage-to-orbit device.

Skylon could do well here.

Nothing is wasted

Just as enticing are the potential applications on terra firma.

In most kinds of engine and electronics, heat is an enemy, robbing them of efficiency.

Reaction Engine's heat exchange know-how, if developed, would benefit not just jets, but also power stations, cars, trains and buildings.

If this year's tests are successful, developing Sabre to its full potential will still take millions, perhaps billions of pounds.

So-called practical minded people will say that we simply cannot afford it. The reality is, we cannot afford not to.

Even if Skylon's tests are not wholly successful, the lessons from past development tell us that nothing is wasted - new knowledge will find applications.

City financed

The question for governments over the decades has often boiled down to "make or buy".

Making means earnings - from sales, intellectual property and education.

Buying means exporting wealth and we must recognise that in years to come, going this route will make the UK a less important global customer, less able to negotiate the best terms, and this will accelerate the downward economic spiral.

To avoid this, we must learn to value what we create.

This is why the Institution of Mechanical Engineers is running its Engineered in Britain campaign to promote the value of UK manufacturing to our economy.

We must overcome an institutional fear of failure and short-term focus, whereby investors write their exit strategy first and support plan second.

Equally, we should stop bashing the bankers. Engineering and the City can and must work together, as another space-based example demonstrates.

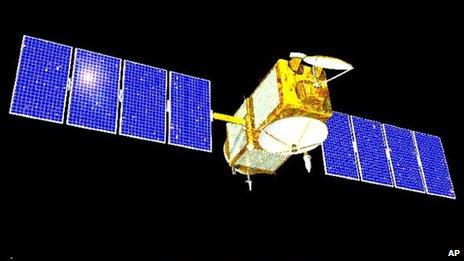

Hylas 1 is a communications satellite, launched into orbit in November last year, which is now being coaxed slowly into full operational life.

It will deliver broadband coverage from space and connect users in remote areas across Europe not served by wire-based networks. Thus it will serve a market estimated to include more than 70 million people.

That Hylas 1 is the first satellite service of its kind is interesting enough.

More remarkable is the fact that it is British owned, designed and built.

Furthermore, this long-term return, high risk, engineering-lead venture, was financed by - wait for it - the City.

Hylas 2, which will extend the service to Africa and the Middle East, is also fully funded and due to launch in 2012.

Great ambitions

And what of the phone in space?

It is a test project, lead by young engineers working for Surrey Satellites, a hugely successful spin-out from The University of Surrey.

In their quest to make small-scale satellites ever more accessible and capable, the company has invested its own time and money in an experiment combining engineering know-how with lateral thinking and an entrepreneurial wiliness to take a chance.

These examples from space show that Britain need not set, as the upper limit of its aspiration, the goal of merely surviving the next decade.

We can grow and even lead, if we capitalise on our evident strengths in innovation, manufacturing and, yes, finance.

Let us look heavenward and change the game.

- Published24 January 2011

- Published18 October 2010

- Published28 September 2010