Russia fights to keep its place in space

- Published

The Soyuz spacecraft have been in operation for more than 40 years

This year is a very important one for Russia's space programme, not least because it will soon celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first manned space flight.

The country has committed billions of roubles to building its own national spaceport in the far east of the country, and is set to become the only carrier of astronauts between Earth and the International Space Station (ISS) for several years to come.

But Russia also has to decide which brand new space projects it should implement to remain a competitive space player.

With the future of the ISS unclear beyond 2020, the US working on a new generation of spacecraft, and ambitious China further developing its space programme, Moscow could soon start running out of time.

Satellite navigation

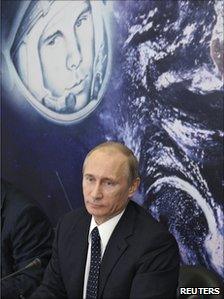

The Russian government would spend 115bn roubles ($3.9bn, £2.4bn) on its national space projects in 2011, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin said last month at an official meeting to prepare the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's flight.

The sum is slightly smaller than the 2011 budget of the European Space Agency and is several times lower than the amount of money available to the US space agency, Nasa.

A big chunk of money is being spent on the Glonass satellite-navigation system, a Russian answer to the US GPS systems and Europe's Galileo, and on some 50 space launches scheduled for 2011.

Mr Putin also said that 24bn roubles would be invested in building the Vostochny spaceport in Russia's Far East in 2011-13, with a further 57bn roubles made available in 2014-15.

According to the government's plan, the first unmanned space launches should take place there in 2015.

'Regeneration project'

But Yuri Karash, a Russian space policy expert, questions the necessity of building the new spaceport now, when Russia rents the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

The rent agreement, worth an estimated $115m a year, will run for 40 more years.

"There are more important and urgent tasks than to build the Vostochny spaceport," Mr Karash says.

Russia will celebrate the anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's flight in April

He points out that Kazakhstan will not force Russia to leave Baikonur, which "is the chicken that lays the golden eggs".

Baikonur's infrastructure is fully oriented on the Russian space programme and, as a result, Russia could not be easily replaced by another nation as the cosmodrome's operator, he argues.

But Andrey Ionin, also a Russian space policy expert, believes that the money committed to building the Vostochny spaceport is only partly "space money", and it is incorrect to assume that the whole sum could be spent on other space projects.

Mr Ionin says that the spaceport "is a new growth point for Russia's Far East", a region in dire need of regeneration, and the government is ready to invest heavily into this regeneration project.

There are many geopolitical, political and social reasons to build a space centre there, while continuing to use the Baikonur cosmodrome, he says.

To some extent, it echoes the role of the USSR space programme for the country decades ago, when whole industries, research institutes and universities were created.

The role of Soyuz

For years, there have been talks of developing new rocket and capsule systems to replace or extend Russia's fleet of Soyuz spacecraft.

They have been flying into space for more than four decades, even longer than the retiring US shuttles.

"They are simple, relatively cheap and highly reliable," Mr Ionin explains, pointing to their long life.

Apart from Russian spacecraft becoming the only means of transport to and from the ISS, with a Soyuz seat available to rent for some $50m, the modified Soyuz rockets are set to start flying into space from Europe's spaceport in French Guiana.

These come in addition to dozens of different launches every year from the Baikonur cosmodrome.

"Commercial launch services represent one of the most competitive areas of Russian activities in the world space market," states the official website of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos.

But Mr Karash believes that without new rockets and ships, Russia could start losing to its competitors.

Mr Ionin also says that "new spacecraft should definitely be developed" in Russia.

Breakthrough projects

All this raises the question of where these new spaceships should be capable of flying.

"Decisions should be made now about which space projects to pursue, as space programmes are long-term and virtually nothing could be done fast," says Mr Ionin.

The expert believes that deep space projects, such as the Mars programme, should be international, as for such missions "it is almost impossible nowadays to assemble the required team of specialist in one country".

He estimates the cost of the international Mars programme to be up to $150bn, while Mr Karash believes that the sum of money Russia would need to spend on its Mars project could be $30bn over 12-14 years.

"Not enough money is spent in Russia on breakthrough and promising projects," says Mr Karash.

But this is true not only for Russia.

Nasa officials have voiced concerns that the current financing does not cover the costs of creating a new rocket and capsule system for deep space exploration by 2016 as required.

Also, the US administration has decided that the country cannot afford a speedy return of humans to the moon.

Mr Karash says that there will never be enough money for all space exploration projects "due to the pure fact that space is really huge".

So, it all comes down to making the right choice of which programmes to finance.

"Everybody is willing to get into space, it is necessary to understand just where our place in space and on the Moon is," Russian President Dmitry Medvedev said earlier this week.