Arab protests pose energy threat

- Published

Most of Libya's crude oil exports go to Europe

With the oil-rich Arab world facing a protracted period of popular revolt and political uncertainty, investors in the energy sector are now planning for the costly and totally unpredictable.

As they do, prices are rising.

Since the protests began, the price of Brent crude oil traded in London has risen by 15%. By contrast, however, US light, sweet crude is little-changed since the beginning of the year.

Gas prices also tend to rise alongside oil, leading to higher petrol and energy prices, especially in Europe.

There is also the risk of shocks to the system if either the oil or gas supply from North Africa to Europe is interrupted.

Finally, energy companies whose contracts were made with outgoing regimes face seeing them being renegotiated or even cancelled entirely as new governments take over.

Oil firms have seen their shares fall during the protests.

So what is actually at stake?

Libya

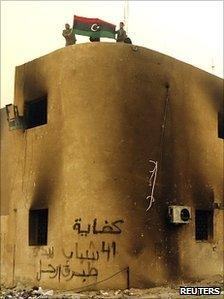

Libyans have been expressing their anger at Muammar Gaddafi's rule

The world's 12th-largest oil exporter with the largest reserves of oil in Africa - according to BP's Energy Statistics Bulletin for 2009 - Libya is the most important from an energy viewpoint.

Until the middle of the last decade, investment was limited by international sanctions, but Italy's ENI and Austria's OMV and Spain's Repsol have relatively long-standing operations.

When sanctions were lifted, Libya invited more firms to exploit the country's apparently vast reserves. Both BP and Royal Dutch Shell signed major deals to explore for both oil and gas, alongside others such as Statoil and Russian firm Gazprom, which took a stake in ENI's operations.

Since the violence erupted, almost all firms have announced that they are pulling out some or all of their expat staff. A strike reportedly shut the Nafoora oilfield and protests also closed the Rus Lanuf oil refinery.

The violence is beginning to have an impact on oil exports. Repsol has ended all production in the country and there have been reports that the countries' oil terminals were no longer functioning.

Almost all Libyan oil goes to Europe, with Italy the main customer. Italy is also the largest recipient of gas, via a pipeline between the two countries.

"If there is a disruption, it could be particularly sensitive just because of the very short distance involved," warns Richard Swann from Platts.

"If you have a long-term contract to buy Libyan crude which comes to you regularly, it would be hard to replace quickly."

Company share prices could also be hit further, as their contracts are not secure. "Their security apparatus is very divided," explains John Mitchell from Chatham House, "so what kind of government would we get? Would the government honour previous deals?"

Algeria

Algeria produces more gas than any other country in Africa, exporting both by pipeline to Italy and Spain and via a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal around the world - including to the UK's natural gas terminal on the Isle of Grain.

There have been protests in Algeria this month

BP is Algeria's largest foreign investor, with two huge gas fields - one, the In Salah field, a joint venture with Norway's Statoil.

The two firms are even trialling carbon capture and storage in the country, an idea they hope to export to the West. Other firms include BG Group.

With so little information on events in the country, it is impossible to predict the impact on gas supplies of the protests.

A supply disruption would undoubtedly have an impact on energy prices in Europe, but there is no evidence this is happening yet.

Egypt

Crucially, Egypt controls the Suez Canal and pipeline. Estimates suggest as much as 4%-5% of the world's oil is transported through them.

Egypt is also an oil producer, producing about 1% of the world's total output, but because of its large population, it consumes almost all of it.

Egypt has been celebrating the downfall of President Mubarak

The country has recently discovered several major on- and offshore gas fields, exporting to the US, Spain and UK amongst others. Production is expected to increase significantly if the country stabilises.

As in Algeria, BP lays claim to being the largest single foreign investor in Egypt, despite selling some assets to US firm Apache.

BG Group says it produces 35% of the country's gas, while Shell also has significant operations.

Although concerns over the canal have receded, energy firms will have to wait and see whether the new government respects their contracts.

"The contracts are seen as generous," argues Mika Minio from Platform, an NGO which monitors the oil industry in the region.

The rest

Tunisia, Bahrain and Yemen also have a significant if more limited energy role. In Tunisia, BG Group is the largest producer, providing 60% of gas production there, and supplies have been little affected by the country's revolution.

Yemen has recently completed a new LNG terminal through a joint venture with France's Total. Business Monitor International says the gas infrastructure has been attacked by local militant groups, but it does not anticipate any impact on global supply.

Bahrain has two oil fields and although neither produces significant amounts, unrest in the kingdom still seemed to increase the price of crude.

"The problem is that the money managers playing on the paper markets in New York and London will see it as a Mid-East worry," therefore assuming oil will be affected, says energy expert Professor Paul Stevens of Chatham House.

Where next?

"For decades the great unknown in the oil industry has been what would happen if the House of Saud were to collapse," says Holly Pattendon, head of oil and gas analysis for Business Monitor International.

With production of 10 million barrels of oil a day, any hint of unrest in Saudi Arabia could upset global oil prices, as could further trouble in another big producer, Iran.

But despite the fears the disruption of oil supplies seen so far is unlikely to cause any shortages. The boom of so-called shale gas in the US means global gas supplies are relatively plentiful - and Saudi Arabia has yet to see a single protester.

Indeed, energy expert Prof Dieter Helm argues this could all end up reducing prices and helping energy firms.

"More democratic and representative governments might be rather better at getting the oil and gas out than the incumbent dictatorships which are being overthrown," he says.

- Published22 February 2011

- Published21 February 2011