India: The next university superpower?

- Published

Students queue for application forms for Delhi University - an institution with 300,000 students

India has ambitious plans to increase graduate numbers in a way which would give it the size and status of an education superpower.

The figures are staggering. India's government speaks of increasing the proportion of young people going to university from 12% at present to 30% by 2025 - approaching the levels of many Western countries.

It wants to expand its university system to meet the aspirations of a growing middle class, to widen access, and become a "knowledge powerhouse".

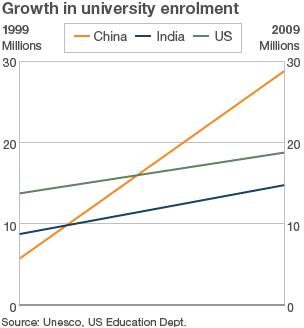

It will mean increasing the country's student population from 12 million to over 30 million, and will put it on course to becoming one of the world's largest education systems.

"We will very likely be number two if not number one in terms of numbers," says Pawan Agarwal, a former civil servant and author of Indian Higher Education: Envisioning the Future.

With US enrolment stagnating and the UK cutting back on university places, "Indian graduates will become more visible globally, particularly in technical and engineering fields", Mr Agarwal predicts.

'Great leap forward'

KN Panikkar, vice chairman of the Kerala State Higher Education Council, describes India's higher education spending as undergoing a "great leap forward".

The amount of money in the central budget for higher education in the current five year plan (2010-2015) is nine times the amount of the previous five years.

But there is a steep hill to climb. India's National Knowledge Commission estimated the country needs 1,500 universities compared to around 370 now.

Hundreds of new institutions are being set up, including large new public universities in each state. The number of prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Management (IIMs) are being expanded from seven to 15.

India's private university sector is also growing rapidly, particularly in professional education in information technology, engineering, medicine and management where there is huge demand from the burgeoning middle classes.

But that will not be enough. To bridge the gap the government last year tabled legislation to invite foreign universities to set up branch campuses. The Foreign Providers Bill is currently making its way through parliament.

'Fever pitch'

Last year there were reports of up to 50 foreign universities being interested in setting up in India. The hype reached fever pitch in November during the visit of US President Barack Obama and a large group of US university presidents.

UK Higher Education minister David Willetts and the largest-ever Canadian delegation were also in the country, enthusiastically talking of university partnerships.

Some foreign universities are already in place. The UK's Leeds Metropolitan University provides management degrees on a 36-acre campus in Bhopal in central India.

Lancaster University runs courses at the GD Goenka World Institute - a 69-acre site near Delhi. Both institutions opened in 2009 as joint ventures with Indian non-profit partners under existing laws.

Some bring faculty and staff from their home institutions, but even the most prestigious public institutions, including the IITs, are struggling to fill top faculty positions and teacher student ratios are deteriorating.

Foreign institutions able to lure staff with higher salaries will make the situation worse, detractors of the Foreign Providers Bill point out.

Mr Panikkar says foreign and private institutions are not the answer. "If only 1% of the population can afford the fees, then it will be very serious for the country in terms of equity."

Fair access

Access is an important issue for the government which came to power because the benefits of India's rapid economic growth were seen to have bypassed the country's poor.

Students in the chemistry department at the private Amity University in Noida

While more than 95% of children now attend primary school, just 40% attend secondary school, according to the World Bank. That in itself will limit growth in university enrolment.

The World Bank has said India's economic success cannot be sustained without major investment in education, including higher education, with public spending on the sector still lagging behind countries like China and Brazil.

But the gold-rush mentality has dissipated. The Foreign Providers Bill is stuck in a parliament that has done little business since a telecommunications corruption scandal erupted last year.

"There has been some toning down of expectations of foreign universities," said Rahul Choudaha, associate director, World Education Services in New York and a close observer of the sector.

"The public university system in many countries is in crisis, facing serious budget cuts. They are not ready to invest money in partnerships."

Some "gold diggers" were dissuaded as the government made it clear for-profit companies would not be allowed to exploit India's thirst for higher education.

Unlike Singapore and China, the Indian government does not want to appear to favour foreign institutions by providing public money or large land grants.

Duke University, based in North Carolina in the US, has been interested in India for some time.

"We want to develop Duke as a globally-networked university. The best researchers are those connected globally," says Gregory Jones, Duke's vice president and vice provost for global strategy.

'Eastward shift'

But its Shanghai campus will be in operation first. "They [Shanghai] were willing to donate and build the first phase at their expense so it was a financially-viable proposition for us," said Mr Jones.

"It is not yet clear how we will develop our presence in India. It is a complicated reform bill."

An eastward shift in the geography of science and technology is a major draw as international companies set up research and development sites in India and China.

"We are tapping into the research potential of these Asian countries," says Professor Pradeep Khosla, dean of Carnegie Mellon University's College of Engineering.

The prestigious US institution has teamed up with India's Shiv Nadar Foundation to open an engineering college in the southern state of Tamil Nadu.

But these joint ventures are not fully-fledged overseas campuses. "Only a handful of overseas universities are thinking about that seriously," said Mr Agarwal. "But even if they go ahead it will not be enough. They will only increase capacity for hundreds of Indian students, not millions."

That means huge public spending on colleges outside the cities, says Mr Panikkar who has written extensively on social justice in higher education. He believes the enrolment targets are too ambitious given limited public resources and bottlenecks in staffing and infrastructure.

"What is achievable is adding perhaps 10 million students to existing capacity in the next five to seven years," he says.

That would still be a major achievement, but some way from making India an education superpower.

- Published26 February 2011