Can conflict minerals really be controlled?

- Published

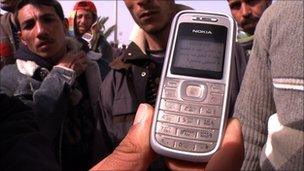

Materials used in mobile phones will be affected by the new law from 1 April

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act, external signed by President Obama in August 2010 will have implications beyond the canyons of Manhattan and the wider US.

This law is not just about making America's financial systems safer - it stretches thousands of kilometres to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Coming into effect on 1 April, it forces any manufacturer subject to US regulation to report on how it sources its so-called conflict minerals - such as cassiserite, coltan and wolfranite, which are mined in the DRC and widely used in mobile phones and laptops.

But how prepared are these countries to comply with the US ruling, and how easy will it be for US companies to trace the ultimate source of the minerals they buy?

Dubious links

Some of the proceeds from these rare minerals have been used to fund conflicts in the region, creating some of the worst humanitarian crises on record.

Some of the profit goes to the foreign companies that buy the minerals, which are then exported to places like Rwanda and South Africa.

Some of the money goes to Congolese export houses, and some of the money goes to the rebel groups who tend to press gang civilians into doing the mining for them.

DRC is a poor country, but many people have become very rich.

One basket, which a person can carry on their head, can contain minerals worth several thousand dollars.

It can be flown by plane, yet people can still make a profit from it.

Getting prepared

Paul Mabolia Yenga, a special adviser to the Ministry of Mines, and co-ordinator of the Kimberley process in the DRC, says the country is working very hard on this problem.

"On a local basis, we have agreements with the German Bureau of Geoscience on certification and transparency mechanisms," he says.

Civilians have been forced to mine minerals by the rival factions fighting in the east of DRC

"We also have an agreement with organisations in the European Union, so all these agreements are part of an effort to have better traceability of our materials," he adds.

He emphasises that the DRC is a sovereign entity and it is doing everything it can to control the material going out of the DRC through the ministry of mines and the different services.

Daunting task

By some measurements as much as 80% of the minerals in Congo may be smuggled out, but Mr Yenga does not think those numbers are accurate.

"There is material going out, but the numbers are exaggerated," he insists.

Reflecting on the problems with diamonds, before the Kimberley Process came into force, he says there was a problem with neighbouring Congo Brazzaville.

"We all had our rules but people just put diamonds in their pocket and disappeared," he says.

"But when we had the international Kimberley Process, Congo Brazzaville was obliged to have some control. We are now trying to do the same with minerals."

He maintains that DRC is creating a data base with all the statistics for production and exports, to enable any anomalies to be tracked.

"We are also creating a mechanism for whistle-blowing to alert us to any improprieties," he adds.

Concerted efforts

The SEC rules mean that US companies will have to look very closely where their minerals are coming from, so there is a chance that DRC will lose business.

The mining industry in the DRC will suffer, because the US companies cannot say with total assurance that what they are receiving is legitimate.

"Our worry is that it is becoming a burden to the people of the US to buy the material out of Congo, because too many papers are going to get involved," Mr Yenga bemoans.

According to Rick Goss, of the Information Technology Industry Council (ITIC), whose members include Apple, Dell, Hewlett Packard, Nokia and Sony, the hi-tech industry has taken the lead on this issue.

"We have pioneered these concrete supply chain processes. There are other sectors of the US industry which are not as well prepared to deal with this requirement as the hi-tech sector is," he maintains.

"This is not an issue that the private sector can resolve on its own," he says.

"It is going to require the concerted effort and attention of international governments, and organisations such as the United Nations, to bring a lasting solution," he says.

"What we have is a humanitarian and political crisis in the Congo and it will take an international co-ordinated effort to address those underlying concerns," he says.

"It is clear from the illegal taxation, from the corrupt activities, that some of the mineral sourcing in the region is indeed being diverted to help fund some of the rebel activities and that is something our industry takes very seriously," he notes.

"Our primary commitment in this effort is to source legitimately and responsibly," he adds.

Will is work?

Can the new rules make it watertight?

There are doubts whether it will be possible to register every location where minerals are mined

There is no combination of private sector and public sector efforts which can lead to that conclusion, according to Mr Goss.

"There will not be a bulletproof solution," he says.

He says it will be impossible to make sure that not one single illicit shipment entered the supply chain.

"It is too complicated in terms of corruption - illegal taxation - to absolutely guarantee that an illegal shipment did not enter the supply chain, regardless of all private and public sector efforts," he warns.

The minerals could go elsewhere. Asian smelters are sourcing from any number of countries.

Are countries ready?

Rwanda has indicated that is it not ready to meet the deadline.

Analysts say Rwanda has the most transparent political system, but it borders the east of Congo, where a lot of the minerals are sourced.

This legislation was passed in July and they simply have not had enough time, according to the mining ministry.

The ministry has indicated that it is worried about losing income - about 30% of Rwanda's income comes from mining.

Smelters who melt down the minerals and then sell them to Apple or Microsoft are worried they will not be buying from them if they cannot produce a certificate saying their minerals are conflict free.

Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) may be a convenient and low-cost means for rapidly determining a mineral's geographic origin.

The LIBS plasma emission spectrum provides a "chemical fingerprint" of any material in real-time.

Rwanda is faced with a catch-22 situation.

The country needs money to purchase the equipment which will make the system work, yet US companies may boycott minerals from the area because they cannot yet meet the necessary requirements.

- Published4 March 2011

- Published25 June 2010