Looking for the next Google

- Published

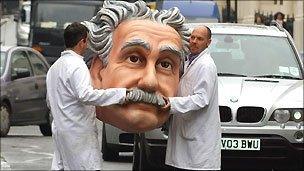

Albert Einstein said: "If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn't be called research."

For a university research project, Google has been successful on an epic scale.

It is the ultimate example of how, in the quicksilver digital economy, a clever idea can be turned into a multi-billion corporation.

There are other online giants that have graduated from campus life. It is easy to forget that Facebook was once only accessible to students in a handful of universities.

It is the type of success that everyone wants to replicate. But how do you find the next Google or Facebook?

Stanford University, in California's Silicon Valley, was where Google began as a research project.

The university has a track record with new technology. Hewlett Packard, Yahoo, Sun Microsystems and Cisco Systems all have roots in this Palo Alto powerhouse.

Stanford says the "entrepreneurial spirit" of its former staff and students has helped to create almost 5,000 companies, employing nearly 700,000 people.

And in terms of externally-sponsored research, including federal projects, Stanford's budget this year is $1.15bn (£714m).

Payback time

The current generation of Stanford students are given advice about how to marry their ideas with money. Other people's money.

The annual Entrepreneurship Week, held last month, included a kind of funding speed-dating arrangement, in which students had three minutes to pitch their ideas to venture capitalists, who in turn had three minutes to give their feedback.

New York is inviting universities to set up a research base in the city to help diversify its economy

The university also has a "coaches on call" scheme, in which students can tap into the advice of business mentors.

Google is repaying the debt to its roots, with a stream of research grants to academics in dozens of universities around the world. It says that it has been likened to a university, with its cafeterias and culture of research.

This link between higher education and innovation is a serious business.

Importing universities to boost the local knowledge economy usually refers to parts of the world that are playing catch-up.

But how about a quiet little backwater called New York? The city's economic development corporation has been inviting universities to set up a science research campus in the middle of New York, with the aim of diversifying the city's economy and promoting start-up companies.

New York wants to bring in a university which can develop "game changing" hi-tech ideas. There has been talk of Stanford or an overseas university wanting to bid for such a branch campus on the US east coast.

Science City

This is a global trend, looking to universities to kick-start high-earning, graduate-employing businesses. They want the type of business ideas you can fit on an iPad rather than in a factory.

ETH Zurich, one of Europe's top universities, is developing its Science City as a research base

ETH Zurich in Switzerland is one of the top-ranked universities in the world. Albert Einstein studied and taught there. Vice-president Roman Boutellier claims the GPS system as the first university spin-off - on the back of Einstein's theory of relativity.

The university is setting up its own Science City, which will place researchers and spin-off businesses in easy reach of each other.

More than 200 businesses have been spun out by ETH Zurich in the past 15 years, in advanced technology areas such as biotech, medical equipment, smartphone applications and 3D images.

"The importance of universities to the economy is growing. It's a big change," says Professor Boutellier.

In terms of finding the next Google, he says universities lend themselves to developing online ideas. Campuses are full of young creative people who can experiment relatively cheaply - and whose ideas can serve a growing market for digital applications.

"In IT you only need a little investment to start with, you need a laptop and access to the internet. You don't have to buy heavy machinery like in the oil industry."

But he also sets out the importance of creating the right culture for such innovation. The ingredients include the diverse, international mix of people and then the academic freedom to explore ideas.

"You need diversity and freedom. Diversity helps to speed up creativity. And only if you have the freedom to apply that diversity can you come up with new things.

"At university you have a high diversity, different nations, different cultural backgrounds, different experiences of life. This diversity is behind the creativity."

Spinning out

The landscape of the global economy is also changing.

David Baghurst is a head of group at Isis Innovation, which develops commercial applications from Oxford University in the UK.

There are plenty of ideas being generated. Isis Innovation averages a patent application every week and has generated 70 spin-out companies.

From university project to a global brand: Google's building in Beijing

But he says there is a big China-shaped question on the horizon.

"The UK's research capacity in universities is world class - but the challenge is how are we going to keep it when there is such enormous investment in the research base in China."

Once China has fully established such a vast research base, he says: "What does the rest of the world do?"

Companies might come to universities looking for "epoch-making ideas", he says.

But what happens if they want to take these embryonic enterprises and carry out their research and development in another country where it's cheaper.

Dr Baghurst says a business such as Isis Innovation can succeed as a bridge linking academics at Oxford with the different demands of industry. It can also talk to businesses and see what they really want from universities, he says.

'Valley of death'

The question of how would-be future Googles might be raised and released into the wild was also examined in a recent European Commission report.

It warned that in international terms, there was an under-investment in the "knowledge base" across the European Union.

In particular it identified what it called the "valley of death" for new ideas, where public funding runs out before private funding can be found to nurture the fledgling business.

It's also far from inevitable what or when an academic project is going to become a commercial proposition.

Professor Boutellier says the mathematical idea of "number theory" has been around for hundreds of years. "But no one knew what to do with it. Today you have number theory and it goes straight to the banks to make a code."

Albert Einstein set out this purposeful pursuit of the unknown. "If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn't be called research."